October 2015 Issue

Read, Comment and Enjoy!

Join Translation Journal

Click on the Subscribe button below to receive regular updates.

A multilingual glossary in higher education: Applying information and documentation skills to improve specialist translator training

- Details

- Written by Lola García-Santiago

1. Introduction

It is indispensable to use terminological resources specific enough for the translator and for the interpreter to be able to carry out their tasks effectively when they interpret or translate scientific, legal, technical, and other specialized documents. The meaning is in the speech (Teubert, 2005), and the specialist translator has to carry out a high-quality terminological work. Corpas Pastor (2001a, 2001b) indeed requires knowledge about the suitability of including a particular term into a context or into certain rhetoric. The choice of a term, especially of neologisms or understanding of new ideas, when faced with a new range which has yet to be accept by the scientific community. This knowledge is written into lots of new scientific papers, which are produced every day and thanks to the Internet and electronic formats, are found in more dynamic communication processes. This perspective follows the corpus-driven approach, supported by Tognini-Bonelli (2001) that takes the corpus data as the primary source of evidence.

Furthermore, the probability of finding a word that has recently appeared in a glossary depends on the possibilities of updating the storage medium, among other things; above all when making an electronic glossary available online (Dorr, B, 1997; Fantinuoli, 2006; Muresan, Popper, Davis & Klavans, 2003; Peñas, Verdejo & Gonzalo 2001 and Zanettin 1998).

In sum, we underline the two possible uses of a corpus (O’Keeffe and Walsh, 2012):

1) The corpus as an end in itself: The design and management of the terminological database.

2) The corpus as a means to an end: The information retrieval skills to find quick and precisely the relevant information.

Understanding the structure of some information technologies that are used to make databases seems too abstract and far removed from their future job. This assertion is even stronger when these translators are in training. If Translation and Interpretation students internalise these core ideas they will benefit from all these tools and even more will be able to create their own tools such as translation memories, glossaries and personal dictionaries. However, Translation and Interpretation Degree students tend to think they can use terminological tools just to seek semantic equivalences or lexical definitions.. These students should be taught about existing instruments and tools, and be instructed in the use and creation of terminology tools, which are an essential part of the translation activity.

In response to this requirement, this study describes our educational experiment over three years with undergraduate students of Translation and Interpreting Degree to discover if our proposal improves their learning about information competencies. It took place at the University of Granada and the student group was taken from the optional subject entitled “Scientific and Technical Documentation”. The activity was voluntary since knowledge of French and/or German was necessary. Therefore the number of participants did not include all of the enrolled students and consequently the corpus may not have been increased in any given academic year.

A twofold aim was established and carried out in two separated stages. The first aim of this experiment was to introduce students to the specialist translation environment based on our own tools which, and at the same time, they were produced using their documentation and information retrieval skills. At the beginning work was focused on encouraging students to create a new tool that could be used as a reliable resource that supports the translators’ work when they look for a terminological equivalence as well as on the supralinguistic competence when it comes to writing the translation. Most of the studies described thus far have been limited to teaching specific linguistic competencies or to build tools for students. Here it is proposed, however, a learning methodology that focuses on the quality of the information search tools, in addition to good terminological extraction and translation, rather than the number of results stored.

The second aim focused its attention on the GloDoc analysis and evaluation from the point of view of a specialist user from the field of translation. We accomplished this part of the study throughout the third year.

The paper is organized as follows: in Section 2 the methodology regarding the creation of GloDoc and the stages in which students participated are explained. Section 3 presents the final tool and the main characteristics of the usability survey and the analysis of its results. In section 4 we discuss and bring attention to some of the results and finally, in section 5 we draw quite positive conclusions.

2. Methodology

To reach our first aim that consists in students design and build a terminological tool, we have created GloDoc. GloDoc is an online multilingual glossary specialized in documentation, information and communication field. Its corpus (EAGLES, 1996), incorporates each term in a semantic context and works with four language pairs, Spanish-French and Spanish-German, in the form of both direct and inverse translation.

We divided the process to obtain GloDoc into the following stages:

• Glossary design

• Corpus creation using scientific articles on documentation, information and communication written in Spanish, French and German.

• Extraction of technical single words and compound expressions from the selected papers.

• Standardization of these previous terms and transformation into entries.

• Production and development of a terminological database using computer tools.

• Online access of GloDoc for public use.

At the same time, the communication and transmission of material to feed into the GloDoc Database was carried out by the e-learning platform Moodle.

2.1. Glossary design

We adapted the design criteria developed by Bowker and Pearson (2002: 54) to the students group. So that, we could observe the main purpose of this project which is to improve teaching methodology skills in information and documentation to complete translator training. Consequently, this glossary is representative of this specific of knowledge.

Priority was focused on the learning process rather than a simpliy compilation purposes. Hence, we used a relational database to work in class easily with a modest volume of entries at the beginning and it would be increased depending on the degree of participation.

Regarding to subject this glossary is specialized in the field of documentation and communication. Due to they had to analyse and translate specialized documents this topic allows to reinforce the students’ knowledge by a double way.

We have designed a multilingual glossary; then students could translate French and/or German texts. In contrast, we have arranged this glossary without English as pivot language. Consequently, in this first version, it was opted to eliminate English from the services offered.

2.2. Corpus creation

In this innovative training project, we have chosen documents that could be as faithful as possible to the documentation, information and communication vocabulary. Throughout the semester, informational skills were taught and practised to avoid collecting irrelevant documents, also technically called documental noise. This meant that it could create the high-quality corpus with only the desired relevant terms. Moreover, advanced searches of bibliographic databases by keywords, Boolean operators, truncation, etc. were set up.

In the first stage, students carried out searches of bibliographic databases specialized in documentation, information science, librarianship and communication technologies. Immediately after, they consulted full-text databases and academic web searchers as Google Scholar to access to the entire document. This kind of search guarantees the authorship and the quality of the document without having to make inquiries at each institution specialising in this subject.

The selection of scientific articles as the only information source to feed the initial corpus was decided based on the principle of working with the most representative documents and the most conventional material in specialized translation at the present. This does not prevent other types of equally valid documents such as pre-prints, reports, etc. from being included.

In order to cover as much lexicon as possible, we made a heterogeneous collection of scientific articles accessible via Web. They dealt with any topic within the field of librarianship, information, documentation and communication. They were from international institutions such as IFLA or from monolingual scientific journals.

The collection was divided in three languages: French, German and Spanish, and each student managed original documents separately. Then, we identified each of the relevant sentences from the articles.

Next, the words and expressions that would feed the terminology database for each language were identified. As was explained before, English was not included as a fourth language to avoid a great imbalance during the development of the database. However, people who wished to do so could search for articles in English, even though it was not included in the database, thereby reinforcing the knowledge they acquired throughout the course. Moreover, the documents delivery and terms identification was done by electronic means as well as the database creation and access.

As a result GloDoc has a corpus that complies with the following technical requirements (Parodi, 2008):

• It has to be composed of texts produced in real situations.

• It has to include examples of a wide range of materials to be as representative as possible.

• It has to be available in electronic format.

• This tool has to have a clear origin.

2.3. Selection of terminology

For the terminology extraction from the selected articles to feed the corpus, we have chosen a manual process using spreadsheets and relational databases. Each text was analysed, and each sentence was isolated and was assigned an identifier. Hence we guaranteed the project was adapted to the digital literacy of all the students who participated in GloDoc’s construction and development stage. Each student had to read the selected scientific papers within a certain topic. He or she then extracted and compiled simple terms or compound expressions due to they didn’t appear in dictionaries or because they were unknown to him or her.

In this stage, the appearance of terms was identified individually and in concurrence with other words. This obtained better results than by using automatic extraction software owing to the limited volume of texts to be analyzed. And furthermore, stop-words could be included in the compound expressions, whereas an automatic terminological extractor omits them, unless a sophisticated list of exceptions could be prepared. In other words, the loss of potential terminological expressions was avoided, thus achieving a greater exhaustiveness of entries. Consequently, participation in this project has promoted an expert knowledge in students (by identifying conceptual structures and relations among concepts), by identifying syntagmatic structures, as López-Rodríguez and Tercedor-Sánchez (2008) state.

Only specialized expressions were included in the glossary with certain exceptions that will be explained later. At the same time, a wide range of examples of expressions used in a paradigmatic or specific way were discovered.

Other information resources, such as the reference material, were widely used by students. In their role as translators, they consulted specialized dictionaries, glossaries and encyclopedias in order to:

• Carry out a lexical analysis

• Generate semantic tags or notes

• Validate and complete the results, especially in the case of acronyms.

• Disambiguate terms where required.

• Find synonyms that can be found in the list of terms

• Compare these sources using judgement, reflection and critical thinking

• Translate German terms into Spanish and find examples (given the shortage of volunteers with knowledge in this language).

It is worth noting, however, that all synonyms were accepted since it is not a controlled documental language but a specialized terminological tool, which contains those expressions frequently used in the field selected for this project.

2.4. Standardization of entries

We created an index with the standardized form of the selected terms, to facilitate the subsequent searching tasks. The criteria used follow the main rules included in most dictionaries and other terminology tools. Consequently, the terms identified were stored as entries in the masculine singular form in the case of nouns and adjectives; infinitive if they were verbs; and these guidelines were combined for compound expressions. Therefore, each term is shown in its original form in terms of gender, number, or tense in the sample phrase included in the database. We have explained all these instructions in GloDoc’s help section for successful searches,

Owing to abbreviations that may appear in any text written in German, both general and specialized (by instance usw. is equivalent to etc., and Vgl means to compare), we decided to include them, despite not being an aim of this glossary. In this version of GloDoc, we included abbreviations in the terms field based on pragmatic reasons. As the number of abbreviations increases, they could be migrated into a specific record field.

On the other hand, the tasks performed on contextual phrases consisted of editing and revising them to prevent the loss of semantic meaning and also to adapt them to technical limitations of the database field (256 characters). Immediately after, the students added other lexical and semantic information to the Spanish language.

Finally, acronyms appearing in selected texts were processed differently depending on importance and complexity. The developed name and its Spanish translation, if it exists, or English translation if it does not, were identified. Furthermore, this design allows acronyms to be found for language pairs to avoid misidentification of acronyms according to the language.

2.5. Development and Management of the database

In this study, we developed a relational database on a single server. The advantage of this tool is its flexibility, thanks to its set of tables collecting the different terminologies, as well as the possibility to add new links. In fact, we generated a group of tables by language and by common features. Next, we established inks among the tables and among the words with the aid of the term identification numbers. This technique allowed great flexibility and speed when the searches would be performed.

Once the entries were made, the relations system between terms and their context was added. The only limitation of this software is that there is a maximum of 255 characters by field. Consequently, some of the sentences, which give context to the expression, had to be edited to fit it into the field length.

At the same time, we carried out a semantic analysis of terminology and we identified linguistic equivalences between pairs of languages (Spanish-French-Spanish and Spanish-German-Spanish), and synonyms.

As noted above, GloDoc does not use a pivot or bridge language to translate, as most existing multilingual automatic translators and glossaries on the Internet do. The terms are extracted directly from the papers. In other words, due to the limited number of documents analyzed it is not possible to find the same number of expressions in each of the three languages. Consequently, not all terms have equivalents in other languages and in their corresponding contexts.

2.6. Online implementation

We have written the GloDoc’s home page in three languages and this provides access to the Search function. Moreover, the students have included grammatical information and have assigned a descriptor to fit the term within one of the large subject areas.

As regards topics, we have compiled a list of subject categories. This list is a merely guide for novice users in the field of communication and documentation but, logically, not a rigorous classification (see table 1). From the perspective of accessibility the design tended towards simplicity in relation to communication with users by formulas, and the arrangement of the elements is tidy, with common structural elements on every page: mainly header lines, logo and menus.

2.7. Evaluation and analysis of use

In the last year of this experiment, we have conducted a survey on the use of GloDoc by the Moodle platform. There were multiple choice questions, Likert scales and qualitative questions which could include comments in free text. The responses from the 9 questionnaires correspond to the volunteer students who had participated in the academic year 2012-2013. Some items also include comments and opinions about how translators worked with this terminological tool and as an aid to understand the translation process.

3. Results and discussion

In this section we present and discuss the results of our experiment with GloDoc and translation and interpreting students.

In terms of our actual findings within the study, we can calim that is has several implications. Firstly, we have introduced our student into Information Science and Documentaton area by creating a new terminological tool with a specialized corpus and we have observed the positive reaction among students. In the same way, it would be necessary to develop new eperiences to connect these information skills and corpus linguistics in group teaching classes.

It is interesting to note that the terminology selection process has had the added educational value that it aroused curiosity in students who went into detail about documentation area in a personal, dynamic and sensible way. Consequently, participation in this project has promoted an expert knowledge in students by identifying syntagmatic structures. Then, our general aim of improving the learning about information competencies has been reached.

In relation with our purpose to create a collective specialized tool, we have obtained our own multilingual corpus. GloDoc online is available for translation, interpreting, information and documentation professionals who work with specialist documents. At present, it has more than 24,000 entries, which identify pairs of idiomatic expressions with their corresponding sentences of context. For example, just in german language we extracted 13346 sentences, which are stored in separated tables of pairs of languages.

Evidently, infrastructure, technical resources and adaptation to the students’ knowledge of computing and documentation allowed the project to be effectively implemented.

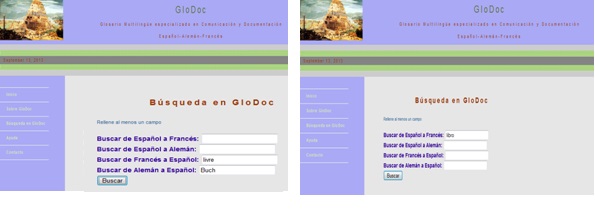

The interface allows the user to query in French, German and/or Spanish. Immediately after, information requested on a particular term, such as examples, equivalences, and so on, is recovered and displayed in the same language. The language selection is done directly by entering the query word in the search field and each corresponds to a given pair of selected languages (fig. 1).

Figure1. GloDoc Search screens

This means that, at the time of search, GloDoc works as a bilingual tool when results are retrieved from the database. The interface supplies all of records of which the entry begins with the term entered in the search field, both single words and compound expressions.

For instance, in German language cases, the results page displays three columns corresponding to the searched term, the translation into Spanish and an example sentence to understand the context. It is also possible to do a multi-field search and to obtain the results from the chosen languages all at once.

Significantly, we have stored and provided more information in Spanish terminology and its equivalent in French (fig. 2). The students have included grammatical information and have assigned a descriptor to fit the term within one of the large subject areas. In addition, there is another field to identify the location of the term or expression within the scientific article. As is well known, the location affects the sentence composition and the role or semantic load of the expression in that context. Therefore, the importance given by the article’s author or magazine’s editor is shown by means of seven possible localizations: title, keywords, abstract, introduction, section title, document body and conclusions.

Figure2. Example of Spanish-French result in GloDoc

For the last aim, we have analized the users’ opinion. The results from the final questionnaire refute the fact that this glossary is very helpful for finding contexts, expressions and collocations from scientific papers on information and documentation; even more if we have taken into account that it has been dealing with current expressions from the real world.

As indicated by the multiple choice question, a satisfaction rate of 100% was obtained because participants found GloDoc’s interface friendly and clear, and searching for information was easy. It is interesting to note, however, that it was suggested to increase the font size to display the results.

The findings about usability have been limited to queries in French because, in the course for that year, no student had chosen German as a second language. The results show, in general, GloDoc is more used for finding words and examples from Spanish to French. 36% of the queries were terms entered in Spanish to find equivalents in French, and 27% conducted the searches in both directions. Only the remaining 18% performed queries from French into Spanish. The students could look for any kind of term freely and the top search terms in the original language (Table 1) are presented.

|

Term |

Number of searchs |

|

tesauro |

4 |

|

documento primario |

2 |

|

documentación |

2 |

|

volumes (fr.) |

1 |

|

texto |

1 |

|

subtítulo |

1 |

|

séquence (fr.) |

1 |

|

revista |

1 |

|

radio |

1 |

|

preprint |

1 |

|

operador booleano |

1 |

|

monographies (fr.) |

1 |

|

metabuscador |

1 |

|

entrée (fr.) |

1 |

|

documática |

1 |

|

digital |

1 |

|

descriptor |

1 |

|

champ |

1 |

|

Catalogage |

1 |

|

caráctere (fr.) |

1 |

|

capacitación |

1 |

|

cablear |

1 |

|

buscador |

1 |

|

bibliografía |

1 |

|

base de datos |

1 |

|

aplicación |

1 |

|

alfabetización |

1 |

|

accesibilidad |

1 |

Table1. Top search terms by survey respondents

This study also found that GloDoc has a high degree of efficiency. Out of a total of 28 search terms in both French and Spanish, only 8 were not found. These unsuccessful queries have been analyzed to be noted and discussed. Firstly, Anglicisms in French searches did not return any results, such as the term preprint. Secondly, queries included terms like radio, to wire or subtitle; while, on the other hand, the starting raw material was composed mainly of papers specializing in librarianship and documentation rather communication. Thirdly, any general word, such as training, can be found. It should also be noted that a typing mistake or misspelling can generate unsuccessful results, as happened with the entry Bolean operaton instead Boolean operator. And finally, only two information searches did not give any results due to the limited number of documents from which the words were extracted (e.g., the terms primary document or volume (fr.)).

With respect to the relevance of the results found, all the students had a positive opinion about the usefulness of the results. They made the following comments justifying their opinion of GloDoc:

• It offers clear and varied contexts

• It helps to understand this course since it covers the fields of librarianship, documentation, information and audiovisual communication.

• It gives more information rather a definition

• It supplies accurate and useful results in form of examples

• It provides terminological equivalences between languages.

Despite the fact that nobody has expressed disagreement, some cases have been found where a term can be used in lots of linguistic and conceptual contexts. Consequently, it would perhaps be necessary to consider a limited number of examples to avoid a page with too many results.

In general, GloDoc supplied enough information 89% of the time and only 11% of people had to consult other sources of information. Another remarkable and positive aspect of this experiment was the active participation to improve the effectiveness of this tool by providing suggestions. They are laid out in the following list:

• To expand the number of languages in this database, especially English.

• To allow the introduction of plural and feminine forms into the search interface

• To remove the limit on the number of characters per sentence

• To identify and link to the full document from which the sentence was taken.

This last comment coincides with an approach considered in the first design stage of the database. However, considering that it is essentially a terminological tool, these data exist in supplementary hidden tables but are not yet accessible by the user.

Finally the practical unanimity with respect to the opinion that GloDoc is an unusual glossary, with great advantages from a usability and practical point of view, must be highlighted. And more specific items concerning example sentences were positively scored. Significantly, all the students expressed that examples were very good for understanding the grammatical constructions and for learning this aspect of the language easily. 89% of the survey responses confirm that they have a better understanding of the meaning and context of these specialized terms with the help of GloDoc examples.

4. Conclusions

The present results have implications for educational practice, owing to specialist translators having to adapt themselves and be trained to respond to any new market demand. The training of these professionals must facilitate the acquisition of language skills, as well as informational and technological skills. These abilities require terminological knowledge and practice in information resources search to reach a continuous update. Therefore academic education should focus on an active practice, which permits the autonomous development and learning.

When are reading, writing or translating highly specialized texts, both monolingual and multilingual specialized glossaries are indispensable tools, especially when it concerns papers that deal with subjects evolving rapidly and constantly, such as information technology and communication.

This article describes the innovative teaching experience with students of translation and interpreting and the product obtained. And theoretical foundations regarding terminology management based on knowledge are the bases on which to carry out this project. Besides we were able to identify specific contexts and difficulties in the glossary building process depending on the language.

As a result of this experiment, GloDoc arises as an innovative project in the translation and contextual terminology areas, which is open and freely available. Thus, this database is the materialization of the interest in expanding the range of terminology resources using relevant literature, terminology and information and communication technology. Furthermore, its functionality aims to improve the work of translators as well as professionals in information, communication and documentation. After this experiment and the subsequent survey, the usefulness for the translator when extracting and representing knowledge from corpus techniques has been demonstrated, since it allows a greater understanding of the subject of specialization and its main concepts.

It also allows a better understanding of phraseology and wording.

An online glossary with a query interface has been developed in this project, which allows information to be retrieved easily and directly from French or German to Spanish, and vice versa. It means that this terminological database does not use an intermediate language, such as English. Distortions of the translation are therefore avoided.

In the final year the use of GloDoc was prioritized over the growth of the database. The questionnaires have demonstrated a better understanding of these types of resources and an analysis and evaluation of them. Also of interest were the critical comments to help improve and develop GloDoc. As was stated in the results section, the issue of results display, number and appearance of examples, the technical and scientific papers from which terms are extracted, and the volume of data, should be further investigated to improve the next stage of this research. Other technical suggestions for improvement should be the best way to feed the database and how to search for a word and its variants by lemmatization and stemming.

In recent years, Web 2.0 systems have been developed and adopted with greater flexibility and are very easy to use. Perhaps it could be possible to produce a glossary using a Wiki to compare the pros and cons of one method or another. The experiment with this project has shown that a Wiki is more dynamic when feeding and increasing the glossary. However, only SQLite allows the reports to be created that identify the search terms and results obtained.

Another possible improvement to this first version of GloDoc could be to include acronyms and to expand the corpus of the database until the whole set of links among all the terms with their contexts is obtained. In addition, a new module should be added to follow the tracks and to automatically analyze the queries produced by each and every GloDoc user.

The students have analyzed the online glossary; they have searched the terminology in a specific subject such as information and audiovisual communication; and at the same time they have identified the sentences that give context and meaning to the terms.

As a result, students have been encouraged and even led to acquire expert knowledge in identifying structures shown in the example sentences in each language.

This experiment confirms the importance of corpus analysis and of the use of languages other than English without using intermediate languages. In addition, the terms classification is essential for integrating specialized and multilingual knowledge in a general framework at the disposal of non-specialist translators.

These experiences are strongly determined by the diversity of languages and the variety of the number of students who choose them when it comes to maintaining a steady growth of the database. Interestingly, in these experiments it has been found that GloDoc has been used more by students for reverse translation. However, the results of this study should be replicated for teaching other foreign languages and with alternative technical resources.

Based on these findings from the survey, comments and course scores, it was concluded that, from a pedagogical point of view this experience has been a success. This training initiative has led to the translation students to actively participate in the field of terminology, and to become involved and have a personal approach to the scope of documentation in an individual, dynamic and reflective way. The findings of this study offered evidence of the effects of being an instrumental method, which integrates experience, self-education and encourages looking at specialized fields in greater detail. It also addresses teamwork and the role of translators and terminologists in advancing interlingual communication in the field of science and technology. By way of final reflection we have observed an increase of marks of the students which have participated in our teaching experience based on applied learning.

5. Bibliography

Bowker, L., & Pearson, J. (2002). Working with Specialized Language: A practical guide to using corpora. London: Routledge

Corpas Pastor, G. (2001a). Compilación de un corpus ad hoc para la enseñanza de la traducción inversa especializada. TRANS: revista de traductología, 5, 155-184. Retrieved from http://www.trans.uma.es/Trans_5/t5_155-184_GCorpas.pdf

Corpas Pastor, G. (2001b). La traducción de textos médicos especializados a través de recursos electrónicos y corpus virtuales. In Actas del III Congreso Internacional de Lingüística de Corpus. Tecnologias de la información y las comunicaciones: Presente y futuro en el Análisis de Corpus (pp.137-164). Valencia: Universitat Politècnica de València. Retrieved from http://cvc.cervantes.es/lengua/esletra/pdf/02/017_corpas.pdf

Cabré, M. T. (2004). La terminología en la traducción especializada. In Gonzalo García, C. & García Yebra, V. (eds.), Manual de documentación y terminología para la traducción especializada. Madrid: Arco/Libros. http://www.upf.edu/pdi/dtf/teresa.cabre/docums/ca04tr.pdf

Dorr, B. J. (1997). Large-Scale Dictionary Construction for Foreign Language Tutoring and Interlingual Machine Translation. Machine Translation, 12(4), 271-322.

EAGLES (1996). Synopsis and comparison of morphosyntactic phenomena encoded in lexicons and corpora. A common proposal and applications to european languages. Pisa: ILC-CNR. http://nl.ijs.si/ME/Vault/V3/msd/related/msd-eagles.pdf

Fantinuoli, C. (2006). Specialised Corpora from the Web and Term Extraction for Simultaneous Interpreters.” In Baroni, Marco/Bernardini, Silvia (eds.). Wacky! Working Papers on the Web as Corpus. Bologna: GEDIT.

GloDoc Online (2012- ). Retrieved from http://wdb.ugr.es/~mdolo/.

Hipp, R. (2012-) SQLite Support. Retrieved from http://www.sqlite.org/support.html

ISO. (1997). ISO 9241: Ergonomic Requirements for Office Work with Visual Display Terminals, International Organization for Standardization. Géneve: ISO.

López Rodríguez, C. I. , &Tercedor Sánchez, M. (2008). Corpora and Students' Autonomy in Scientific and Technical Translation Training. The Journal of Specialised Translation, 9. 2-19. Retrieved from http://www.jostrans.org/issue09/art_lopez_tercedor.php

Marcos, M.C. , & Gómez, M. (2007). La usabilidad en las bases de datos terminológicas online. Glossa, 2(2). Retrieved from http://bibliotecavirtualut.suagm.edu/Glossa2/Journal/jun2007/La_Usabilidad_en_las_Base_de_Datos.pdf

Muresan, S., Popper S. D., Davis, P. T., & Klavans, J. L. (2003). Building a Terminological Database from Heterogeneous Definitional Sources. Proceedings of the National Conference on Digital Government Research. Boston, Massachusetts.

O’Keeffe, A. & Walsh, S. (2012). Applying corpus linguistics and conversation analysis in the investigation of small group teaching in higher education. Corpus Linguistics and Linguistic Theory, 8(1), 159-181.

Parodi, G. (2008). Lingüistica de corpus: una introduccion al ambito. RLA. Revista de lingüística teórica y aplicada, 46(1), 93-119. Retrieved from http://www.scielo.cl/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0718-48832008000100006&lng=es&tlng=es

Peñas, A., Verdejo, F. , & Gonzalo, J. (2001). Corpus-based terminology extraction applied to information access. Proceedings of the Corpus Linguistics. Technical Papers, 13. Special Issue. University Centre for Computer Corpus Research on Language, Lancaster University.

SQLite Manager (2012-). Retrieved from http://dibosa.wordpress.com/dossier/administracion-grafica-de-sqlite-con-sqlite-manager/

Teubert, W. (2005). My version of corpus linguistics. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics, 10(1), 1-13. Retrieved from http://www.corpus4u.org/forum/upload/forum/2005071006505939.pdf

Tognini-Bonelli, E. (2001). Corpus linguistics at work. Amsterdam : John Benjamins.

Zanettin, F. (1998). Bilingual Comparable Corpora and the Training of Translators. META, 4, 616-630.