October 2014 Issue

Read, Comment and Enjoy!

Join Translation Journal

Click on the Subscribe button below to receive regular updates.

Ready..Steady..Translate in the Real World of UAE: Do Undergraduate Translation Programs Meet the Market Needs? Suggesting Avenues of Discussion

- Details

- Written by Tara Muayad R. Al-Hadithy

Abstract

This study investigates the status quo of undergraduate translation training programs offered by UAE universities. It sheds light on how efficiently prepared students are to meet the challenges of the translation industry. It aims to identify the stumbling blocks that stand in the way of meeting the market needs of today’s global UAE. The study also draws pedagogical implications on focal issues related to translation teaching and program development in UAE universities. Due to the major shifts in UAE’s translation profession and the way professional translators operate in the current translation industry, effective changes in academic translator training programs become highly necessary. This paper aims to suggest avenues of discussion as an important step towards suggesting new directions in teaching translation.

1. INTRODUCTION

In today’s global world, the significant role translation plays as a communicative tool has become ever more prominent.The impact that translation has on civilizations made it necessary for those nations who want to successfully ride the waves of globalization to invest in translation. Being a pioneer in the Gulf region, UAE has successfully endeavored to promote translation through distinguished projects like Kalima and Tarjem. It has also institutionalized translation via corporate and academic providers of training. Many UAE universities offer translation courses and degrees on both the undergraduate and postgraduate levels. The University of Sharjah, The American University of Sharjah, Ajman University of Science and Technology, The United Arab Emirates University, and Abu Dhabi University are among the first universities to offer tertiary translation training in the UAE. More recently, The Canadian University of Dubai and The American University of Dubai have both launched degrees in translation to effectively address the lack of translators in the UAE.

Opening new translation programs is one important way to offer more students in UAE the opportunity to consider translation as a career option. One other important means to attract more students into this challenging profession is to teach it in such a way that best meets the requirements of the translation market. In order to equip our students with the required skills to become the future translators that meet the needs of the professional world and job market, the first step should be to examine the teaching methodologies adopted in the translation classroom.

In an attempt to distinguish translation in the classroom from other types of translation, Willigen-Sinemus (1988:472) cites the Honig and Kussmaul’s comment:

The students translate a text which they do not understand for an addressee whom they do not know. And the product of their labours is not infrequently assessed by a university lecturer who has neither practical experience as a translator nor theoretical knowledge of translation science.

In the case of translating into the foreign language, Willigen-Sinemus plausibly adds “[the students translate] into a language they have not as yet mastered.” He distinguishes two kinds of translation activities in two kinds of classrooms:

- Translation-learning activity in classes intended to teach students how to translate. The students already have a high standard of proficiency in target and source language.

- Language-learning activity used during second-language acquisition classes. The students “are not very proficient in the foreign language and sometimes not in the mother tongue either.”(ibid)

According to my humble experience as both a freelance translator and translation instructor, I have come to witness a third type of translation classroom commonly existent in the tertiary translation programs offered in UAE. This type of translation is an amalgam of the above mentioned types. Students are enrolled in programs offering a bachelor’s degree in the English Language and/or Literature, and translation courses are given to fulfill the requirements of their academic study plan. The students, however, lack a high standard of proficiency in the foreign language (English) and to a lower extent, in their own mother tongue (Arabic) too. In an interview with the University of Sharjah’s chair of English Language and Literature, Dr. Abdul Sahib Ali links the decline of degrees such as translation to the decline of classical Arabic. “People tend to use the colloquial, daily Arabic. Standard Arabic is rarely used these days,” said Dr. Ali to The National (August 22, 2012).In many cases, the instructor is obliged to shift to (pedagogical) translation as an aid to language learning.

Thus the success of institutionalized translation programs in the UAE, especially in the undergraduate level, is reliant on a curriculum customized to the learning needs of this converged type of translation-learning class where students are enrolled with a minimum score of 5 or 5.5 in the International English Language Testing System (IELTS) exam. Moreover, the goals and learning outcomes of today’s translation programs should align more with the reality of professional translators in the 21st century. In other words, “our teaching methods should adapt to the times and draw more closely on the realities of the market, casting aside the artificiality that sometimes characterizes translation activities in formal education.”(Giles, 1995 qtd in Olvera Labo et al, 2007).

2. THE PRESENT STUDY

2.1 Significance

A lack of interest in acquiring an academic qualification in translation has been noticeable recently in the UAE, especially at the undergraduate level. In reaction to this withdrawal, a number of universities started initiating translation programs. To ensure the success of this endeavor in the UAE, reviewing the current state of translation tertiary programs in the light of the Emirates National Qualifications Framework-(the QF Emirates) becomes an imperative. The present study recognizes the pressing need for the exploration of translation issues related to the general profile of translation educators and their teaching methodology, and how these meet the present market needs in the UAE context. Indeed, initiating these avenues of discussion is a significantly important step preceding the proposal for new effective directions in tertiary level translation training.

2.2 Aim

The aim of this study is two-fold. First, the study highlights the flaws in the current translation programs offered in UAE universities. Second, the study seeks to explore more plausible definitions of translation competence and translation teaching methodology that if adopted, aid the alignment of the learning outcomes of translation programs with the QF Emirates learning outcomes.

2.3 Procedure

This analytic study sets out by recognizing and defining the type of translation classroom in the UAE academic context. Within a comparison between the traditional and the modern translation teaching methods, the study clarifies the need for new directions to highlight that it is time to revolutionize university translation programs in order to meet the QF Emirates learning outcomes. Translation competence of the modern translation classroom no longer remains viable once put against today’s market needs and the prerequisites for becoming a professional translator. The discussion reaches the researcher’s recommended definition of translation competence in the light of meeting the QF Emirates criteria. The gap between market needs and translation training programs is highlighted and potential suggestions are made.

2.4 Limitations

This study is constrained by an analytical rather than empirical research approach. This is mainly attributed to the fact that investigating the relevant variables of translation programs in the UAE before embarking on collecting data on subjects, assessment tools, materials used, etc. constitutes a logical sequence. Reflections on the status quo of the translation classroom in the UAE context lays on the researcher’s table the important factors that need to be qualitatively and quantitatively measured in a phase two of this study via empirical means of research.

3. THE TRADITIONAL VS. THE MODERN TRANSLATION CLASSROOM: A NEED FOR NEW DIRECTIONS

Any proposal for a modern way of teaching translation should be discussed against the background of traditional translation training in general. Many translation specialists have criticized the traditional translation classroom and deemed its teacher-centered approach as obsolete. (Kiraly 2000a; Jaber 2002; Colina 2003; Stewart 2008). In his critical view of the traditional translation classroom, Kiraly views the students’ role as that of passive absorption, and the teacher becomes, “a repository of translation equivalents and strategies that are to be made available to the entire class when one student displays a gap in his or her knowledge by suggesting a faulty translation” (Kiraly 2000a: 24). This mainstream translation educator suffers from what Colina (2003:52) has termed as the ‘Atlas Complex’ where the teacher “carries over his/her shoulder the full responsibility for all that goes on in the classroom” (ibid). This teacher-centered classroom gives the impression that there is only one correct answer-that of the teacher’s. It is also detrimental to the students’ autonomy and self-confidence (ibid: 52-53).

This out of date approach to teaching translation adopts an ‘Un-creative’ pedagogy in which McWilliam (2008) describes the teacher as a ‘Sage-on-the stage’. McWilliam not only supports the pedagogies that lead to the ‘unlearning’ the teaching methods of this dominantly ‘transmission culture’ which have in the process given birth to the ‘Guide-on-the side’ educator, but she has been ambitious enough to promote the emergence of ‘Meddler-in-the-middle’ (ibid). McWilliam calls for re-positioning the teacher and student as co-directors and co-editors of their social world. She is not satisfied with a pedagogy that just shifts focus from teacher to learner as this “does not capture the need for experiment and error-making” (ibid: 265).

A translation program that aspires to attract more student enrollment, maximizes retention, and equips its graduating students with the required professional skills that meet the present market needs should not only be learner-centered and eliminate the all-knowing teacher figure. It should comply with the true mission of higher education that focuses on the education of students as “creative, intelligent and competent human beings equipped with well-rounded translation competences rather than with a narrow set of techniques” (Tan, 2008: 593-594). This holistic profile of the translation student should be supported by a holistic translation syllabus that moves towards ‘a whole-person translation education approach’ (see Tan 2008). A ‘whole-person education’ would make students well rounded by being trained and educated to “gain generative problem-solving abilities, using definite resources to handle infinite new situations” (ibid: 596). Based on the above mentioned advantages of a the ‘whole person’ education approach to teaching translation, the present study recognizes that the viability of conventional approaches for educating translators in UAE universities should be reconsidered for two main reasons:

- The demands of today’s translation market in UAE introduce challenges that cannot be met by a teacher-centered translation approach.

- The learning outcomes set by the Emirates National Qualifications Framework for achieving nationally and internationally accredited tertiary qualifications require a balance between the professional and academic sides of translator training and education. (See 2.1).

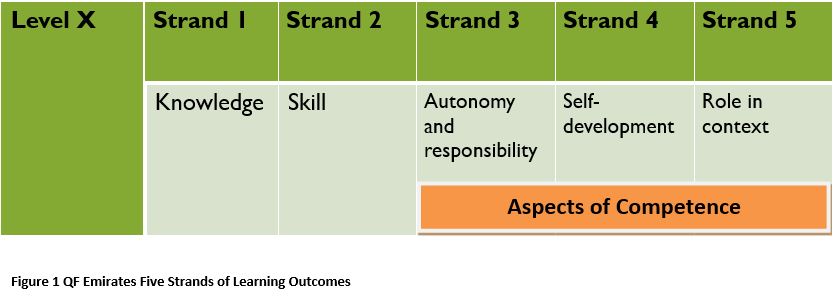

3.1 TOWARD MEETING THE QF EMIRATES

In its attempt to obtain national and international accreditation, the UAE National Qualifications Authority has on the 20th February 2012 approved the qualifications framework for the UAE known as the QF Emirates. (HUwww.nqa.gov.aeUH). The Framework sets five ‘strands’ of learning outcome statements for ten levels of qualifications. The QF Emirates recognizes that learning outcomes define what learners have learned and not what they have been taught. The strands are: knowledge, skill, and aspects of competence, comprising three strands – a) autonomy and responsibility, b) role in context, and c) self-development. (See figure 1).

The researcher’s argument is that to acquire student autonomy, creativity, responsibility, independence, and self-development, students must liberate themselves from their instructors. For Kiraly (2003:31) this is the main requirement that translation students must meet if they are to graduate as self-confident translation professionals, “prepared to think for themselves, to work as members of a team, to assume responsibility for their own work, to assess the quality of their own performance and to continue learning once they leave the institution.” To align with QF Emirates learning outcomes, the goals of the current tertiary translation programs in UAE must help students develop their own ‘self-concept’ and to assist “in the collaborative construction of individually tailored tools that will allow every student to function within the language mediation community upon graduation” (ibid). This new direction creates several pedagogical implications. One important pedagogical implication of this study’s adopted ‘Whole person education’ approach is on the level of translation competence acquisition.

4. TRANSLATION COMPETENCE: A NEW DEFINITION

Newmark (1995) identifies the essential characteristics that a good translator should have:

- Reading comprehension ability in a foreign language

- Sensitivity to both mother tongue and foreign language

- Knowledge of the subject

- Competence to write the target language dexterously, clearly, economically, and resourcefully.

These widely accepted characteristics are limited to only linguistic competence. The argument is: can linguistically competent translators be ready and steady to practice translation professionally in a way that meets the demands of today’s market needs? When the learning outcomes of translation syllabi are set to enhance the knowledge of students in translation concepts, theories, and procedures are they thus equipping students with what it takes to translate professionally? Although linguistic competence is a necessary condition, it is not yet sufficient for the professional practice of translation.

To acknowledge that translation competence comprises more than linguistic competence represents a turning point in the study of translation teaching and training. According to Orozco and Albir (2002: 376), many authors fail to explicitly define translation competence. In fact, Orozco and Albir state that they found only four explicit definitions of translation competence, which are: Bell (1991: 43) defines translation competence as “the knowledge and skills the translator must possess in order to carry out a translation”; Hurtado Albir defines it as “the ability of knowing how to translate” (1996: 48); Wilss says translation competence calls for “an interlingual supercompetence [...] based on a comprehensive knowledge of the respective SL and TL, including the text-pragmatic dimension, and consists of the ability to integrate the two monolingual competencies on a higher level” (1982: 58). Finally, the fourth definition, the one Orozco and Albir adopt in their article, is that of PACTE research group2 (see PACTE 2000), which defines translation competence as “the underlying system of knowledge and skills needed to be able to translate.” This translation competence is made up of various sub-competences (PACTE 1998 qtd in Olvera Labo 2007): communicative; extra-linguistic; instrumental-professional; psycho-physiological; transfer and strategic. “These competences interact, and the student adds to them another, namely learning competence, which refers to the specific strategies a learner must develop” (ibid).

Out of the four above mentioned ‘explicit’ definitions of translation competence only the fourth definition exists within a teaching approach that is both learner-centered and career-oriented. The acquisition of this type of translation competence should be the goal of modern translation teaching methods. As PACTE (2000) has pointed out that the development of translation competence in student translators today not only means the training of their linguistic-cultural skills, but also IT skills, marketing and other related problem-solving abilities as well.

5. UNIVERSITY TRANSLATION PROGRAMS AND MARKET NEEDS: IDENTIFYING THE MISSING LINK

A quick glance at the activities involved in translation industry listed on the Translation Services website HUwww.thelanguagetranslation.com/services-industry.htmlUH reveals that besides translation into various languages, various activities are involved in the translation industry to produce the final error-free product:

- Translation

- Translation revision: Verification, Correction, Editing, Proof reading

- Terminology: Specialized domain vocabulary

- Interpretation: Spoken language translation

- Language technology: Production of computational tools, R&D

- Translator training

- Post-editing: Machine translation revision

- Translation management: Project coordination

- Audiovisual translation: Dubbing, subtitling of film, TV

- Localization: Web sites, software, documentation

- Technical and professional writing: Collaboration with translators

- Post editing: Machine translation revision

This list not only shows what it takes to be a professional translator and the spectrum of translation competence involved, but also indicates the missing critical link in translator training in UAE university translation curricula.

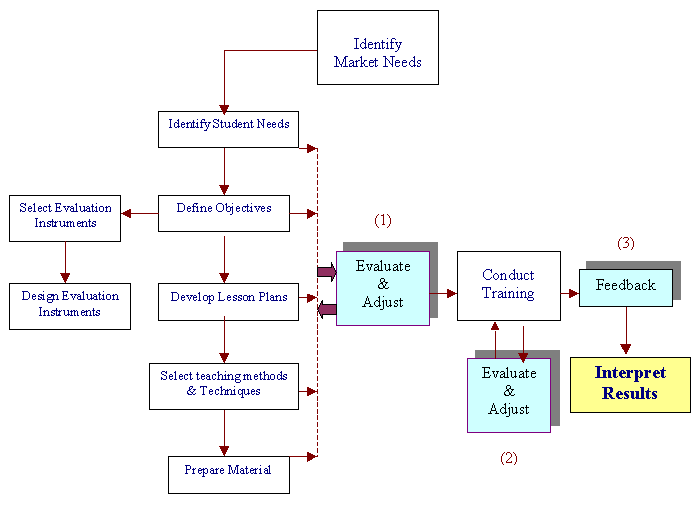

Training processes, according to Gabr (2001), are a collective effort that should aim at improving the student’s individual performance to qualify him/her to join the profession. Thus, Gabr emphasizes that it is for this reason that university translation programs should be viewed as a collective undertaking that requires close cooperation, coordination and meticulous evaluation by all parties involved in the training. Gabr states that in order for a training course to bear fruit, it has to be monitored, or in other words, evaluated. He clarifies that the evaluation process may be conducted either at intervals or at the end of the course. To achieve the goals of evaluation, he recommends that the evaluation process be conducted at the pre-course phase, at each step in the training cycle and at the end of the course. This would result in constructive feedback that can be utilized in a timely manner. Gabr (ibid) designs the following model shown in figure 2, which he calls the Comprehensive Quality Control Model (CQCM). It ensures accuracy in designing and implementing each step in the training effort and, eventually, a quality product. It comprises the three levels of evaluation as follows:

- Evaluation at the training development level

- Evaluation at the student learning level

- Evaluation at the student reaction level

Figure 2 Comprehensive Quality Control Model (CQCM)

http://accurapid.com/journal/15training.htm

If adopted, this model would play an effective role in enhancing the syllabus design of translator training courses, the quality of teaching, and the quality of trained students. It offers one means of bridging the gap between university translation training programs and the market needs. Following this comprehensive quality check on translation courses can impact both practical and theoretical courses. For example, the students’ feedback can be turned into a wish-list of how-to questions that the teacher can address in following sessions. (See Shuttleworth 2001).

6. CONCLUSION

The teaching of translation in UAE universities should bridge the gap between translation practice and translation theory. The modern translation class should shift the focus from the teacher to the learner. In order to move in the direction of meeting the QF Emirates, translation qualifications and degrees should equip students with the knowledge, skills, and competencies needed to meet the ‘labour market’ needs- one of the important ‘Key drivers’ of the QF Emirates. It should also develop life-long learning skills. Moreover, the teaching of translation should empower students by encouraging them to confront and reflect on what Zhong (2002: 580) calls ‘their subjectivities’ to both “celebrate the strength and recognize the weakness of their subjective, interpretive and intellectual power” (ibid). In a nutshell, teaching translation should be process-oriented rather than product-oriented. Students should not be spoon-fed with the teacher’s objective translation product. They are entitled to experience making errors, searching for solutions, translating within a work assimilated environment, seeking references and resources, conducting research, interacting with team members, and making choices just like professionals do in real life work contexts.

REFERENCES

Bell, R.T. (1991): Translation and Translating, London: Longman.

Colina, Sonia (2003). Translation Teaching: From Research to the Classroom. A Handbook for Teachers. Boston: McGraw-Hill.

Gabr, M. (2001). “Program Evaluation: A Missing Critical Link in Translator Training”. Translation Journal, vol 5, n.1. Retrieved 04/01/2013. HUhttp://accurapid.com/journal/15training.htmU

Gabr, M. (2002).“A Skeleton in the Closet Teaching Translation in Egyptian National Universities”. Translation Journal vol.6, n 1. Retrieved 28/01/2013. HUhttp://accurapid.com/journal/19edu.htmUH.

Gile, D. (1995): Basic Concepts and Models for Interpreter and Translator Training, Amsterdam/Philadelphia, John Benjamins Publishing Co.

Kiraly, D. (1995). Pathways to Translation Pedagogy and Process. Kent, Ohio. Kent State University Press.

Kiraly, D. (2000). A Social Constructivist Approach to Translator Education: Empowerment from Theory to Practice, Manchester/Northampton: St. Jerome.

Kiraly, D. (2003). “From Teacher-Centred to Learning-Centred Classrooms in Translator Education: Control, Chaos or Collaboration?” in: A. Pym, C. Fallada.

Kussmaul, P. (1995). Training the Translator, Amsterdam/Philadelphia, John Benjamins Publishing Co.

McWilliam, E. (2005) “Unlearning How to Teach” Unlearning Pedagogy, Journal of Learning Design, vol.1, no.1, p.1-11. Retrieved 09/12/2012

HUhttp://www.creativityconference07.org/presented_papers/McWilliam_Unlearning.docUH

Newmark, P. (1995). A Textbook of Tranlation. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publications Data.

Orozco, M and Albir, A. (2002) “Measuring Translation Comptence Acquistion”. Meta: Translator’s Journal, vol.47, n.3, P. 375-402.

Retrieved 08/02/2013. HUhttp://id.erudit.org/iderudit/008022arUH.

Olvera Labo, M and et al. “A Professional Approach to Translator Training (PATT)” (2007). Meta: Translator’s Journal, vol. 52, n. 3, P.517-528. Retrieved 09/02/2013 HUhttp://www.erudit.org/revue/meta/2007/v52/n3/016736ar.pdfUH.

PACTE. (2000): “Acquiring translation competence. Hypotheses and methodological problems of a research project,” in Beeby Lonsdale, A., Ensinger, D. and M. Presas Investigating Translation, Amsterdam, John Benjamins Publishing.

Qualifications Framework Emirates Handbook, National Qualifications Authority. Retrieved 12/12/2012 HUhttp://www.nqa.gov.aeUH.

Shuttleworth, M. (2001). “The Role of Theory in Translator Training: Some Observations about Syllabus Design”. Meta: Translator’s Journal, vol.46, n.3, p.497-506. Retrieved 29/06/2012. HUhttp://id.erudit.org/iderudit/004139arU

Stewart, D. (2008).“Vocational translation training into a foreign language”. Vol.10. Retrieved 29/01/2013. HUhttp://inTRAlinea.onlineUH

Tan, Z. (2008). “Toward a Whole-Person Translator Education Approach in Translation Teaching on University Degree Programmes”. Meta: Translator’s Journal, vol.53, n3, p.589-608.Retrieved 02/02/2013. HUhttp://id.erudit.org/iderudit/019241arUH

The National (August 22, 2012) “Universities to Address the Lack of Translators in UAE”. Retrieved 29/11/2012.

Translation Services. Retrieved 11/01/2013. HUhttp://www.thelanguagetranslation.com/services-industry.htmlU

Willigen-Sinemus, M.(1988).“Typology of Translation in the Classroom”. Meta: Translator’s Journal, vol. 33, n. 4, p. 472-479.Retrieved 08/02/2013. HUhttp://id.erudit.org/iderudit/004160arUH.

Wilss, W. (1982): The Science of Translation. Tübingen: Gunter Narr.

Zhong, Y. (2002) “Transcending the Discourse of Accuracy in the Teaching of Translation: Theoretical Deliberation and Case Study”. Meta: Translator’s Journal, vol.47, n. 4, p.575-585.Retrieved 19/01/2013. HUhttp://id.erudit.org/iderudit/oo8037arUH