January 2015 Issue

Read, Comment and Enjoy!

Join Translation Journal

Click on the Subscribe button below to receive regular updates.

Cultural Experience, Familiarity with English Idioms and Translation: A Mixed Method Approach

- Details

- Written by Miao-Chi Wu

Abstract

Translation cannot only be a literal type of code switch, but also a cross-cultural interchange. Any kind of language is embedded with cultural perspectives. Language is a reflection of culture and acts as the transmitter for culture. Idioms as a special form of language convey an abundance of cultural information. This paper enters this field by studying the relationship between cultural experience and familiarity with English idioms (FEIs) while the EFL learners are performing idiomatic translation. Thus, a combination of quantitative and qualitative research elements is used in this study. The data were collected from 157 participants (PTs) who were recruited from two departments in a university to complete a questionnaire consisting of open- and closed-ended questions. Drawing upon the findings in this research, a statistically significant difference was found between genders, departments and FEIs with an independent-sample t-test. Similarly, there was a statistically significant difference between cultural experience and English idioms with a contingency analysis. The outcomes of Pearson’s product-moment correlation coefficient were almost identical to Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. The results of qualitative analysis showed the Chinese equivalents provided by PTs who were strongly influenced by the literal meanings of source texts (STs) when PTs were performing idiomatic translations. Some tentative suggestions are proposed to use the cluster or factor analysis to investigate the ways in which the major factors determine the FEIs. The results may contribute to improvements in teaching or learning translation for teachers or EFL learners.

Keywords: translation, cultural experience, familiarity with English idioms,

mixed method, quantitative, qualitative.

Introduction

Does cultural experience influence EFL learners’ translation competence? What is the familiarity with English idioms provided by PTs? Are there any correlation coefficients among variables? While the PTs are considering the correct translation for each English idiom (EI), which codes of cultural experience for EIs will they select? These hypothetical questions are the underpinning of this study. From astute observation, younger generations regretfully are sometimes at a loss to learn the historic heritage of idioms, and disregard the cultural importance of them. One probably knows the idioms; one might not fully grasp the cultural allusions and the meaning of linguistic signs if one could not have the cultural experience (Wu, 2011). An EFL learner, alternatively, can explore a culture by translating its idioms. In other words, translation is like a cultural practice (Wu, 2011a). Based on this reasoning, it is worth investigating the phenomena that occur in relation to cultural experience and EFL learners.

This paper combines elements of quantitative and qualitative research. The rationale for using this combination of sources of data is that a complete picture could not be generated by either single method (Cresswell, 2009). Five research questions are raised. What are the outputs of frequency and percentage of FEIs? Is there any significant difference between genders, departments and FEIs? What are the results of contingency analysis between cultural experience and English idioms? Are there any correlation coefficients between variables? What are the outcomes of qualitative analysis related cultural aspects on 10 texts? Following the analyses, most findings show support for the research questions in this study.

Literature Review

Influences of Culture on Translation

Translation is a cross-language and cross-culture activity. It also involves the creation of linguistic and literary, religious and political, commercial and educational values (Faull, 2004). In other words, there is no language without culture. Thus, the translator has to maintain the cultural context from source language (SL) to target language (TL). While the SL is full of religious culture like a Chinese idiom ‘佛要金裝,人要衣裝’ (Buddha wears golden clothing, man wears an elegant dress) (lit.) (i.e. Clothes make the man), this mirrors the religious cultural barrier to translate this idiom into the TL. Buddhism is more influential in China than in the West. Translators and readers who lack knowledge of Chinese culture may encounter difficulty understanding such an idiom. In addition, knowledge of social values can affect a reader’s comprehension of the translation. Social values are developed by social behaviors among members of the same society. One who judges a person from his/her appearance, such as clothes, reflects a social phenomenon in Chinese society. Thus, the translation of ‘佛要金裝,人要衣裝’ cannot only keep the meaning of the SL, but also transfer the cultural concepts in TL. A translator works with culturally loaded words and needs to keep this in mind.

Cultural Parallels between Chinese and English Idioms

Before discussing culture, it is necessary to define the term idiom. Idioms are expressions that are not readily understandable from their literal meanings. They are an inseparable part of language. They have unique national and local cultural connotations. The English idiom, ‘Fine feathers make fine birds’ (i.e. One dresses elegantly, people will think one is elegant), has a meaning that is similar to the Chinese idiom, ‘佛要金裝,人要衣裝’ (Buddha wears golden clothing, man wears an elegant dress) (lit.). The English idioms of ‘Our life is but a span’ and ‘Life is but a dream’ denote life is short and one can find its meaning. These idioms are similar in meaning to the Chinese idioms, ‘人生如朝露’ (Life is but a morning dew) and ‘浮生若夢’ (Life is but a dream). The English idioms, ‘Still waters run deep’ (i.e. Quiet people are often very thoughtful) and ‘Watch one’s step’ (i.e. To act with care and caution so as not to make a mistake or offend someone) (lit.), have the same meaning as the Chinese idioms, ‘虛懷若谷’ (Empty the bosom like a valley) (lit.) (i.e. To humble oneself) and ‘慎言謹行’ (To speak and act cautiously) (lit.).

Idiomatic Translation Difficulty in Rendering Cultural Terms

Idiom is a type of language formula that cannot be transformed (Ye, 2000). The idiom ‘Man proposes and God disposes’ means that people can formulate any objectives they want, but God decides their success or failure. The structure of this idiom and the choice of words have a religious dimension. Similarly, the Chinese idioms of ‘門當戶對’ (The doors of both sides are well matched), ‘虛懷若谷’ (Empty the bosom like a valley), ‘謀事在人,成事在天’ (Man does, but God decides), and ‘浮生若夢’ (Life is fleeting like a dream) are based on lexical parallelism (字詞對仗), causality (因果關係), visualization (望文生意), and literary elegance of conciseness and expressiveness (簡潔扼要), which are the distinctive characteristics of fixed patterns. While the Chinese idiom is being translated, most linguistic attributes are disappearing (Chen, 2009). One way of translating Chinese idioms is the strategy of ‘semantic translation plus annotation’ (Fan, 2007: 220). Similarly, in translating Chinese idioms, a translator needs to comprehend their meaning first, and then the idiomatic form of the language formula (Chen, 2009). Exoticism is the charm of the unfamiliar. It enables readers to understand other cultures. It is the most difficult element to translate. When a foreigner hears a Chinese idiom, ‘佛要金裝,人要衣裝’ (Buddha wears golden clothing, man wears an elegant dress), but has never visited a Chinese Buddhist temple, s/he might not be able to sense the exotic atmosphere. The exoticism exists in the culture of the target language; this may become a cultural blank or barrier. Expressing the local color to the target readers is another difficult task for the translator.

The Ways in which EFL Learners Access Idioms

We understand the idiomatic meanings by retrieving the content directly from memory. Familiar idioms are comprehended instantly. However, it is difficult for EFL learners (EFLLs) to understand an idiom. While EFLLs are processing the idiomatic expressions with their memory, unfamiliar idioms are sometimes hard to understand. Cooper (1999) claims that EFLLs use preparatory and guessing strategies. The former is to paraphrase, analyze and request the idioms and the latter is to infer the meaning from the context, adopting the literal meaning and using background knowledge of an SL idiom. In addition, the memory of figurative meaning in EFLLs is crucial to processing idiomatic expressions (Lin, 2004). Figurative meaning derives from referential competence such as metaphor, hyperbole, paradox and irony (Gibbs’ The Poetics of Mind, 1999). The figurative (non-literal) competence allows the EFLLs to process the idioms and to select the correct meaning directly from memory. Comparatively, the literal meaning which is an ordinary and primary expression leads an EFLL to guess or apprehend the idioms without much linguistic processing. When an EFLL sees an unfamiliar idiom like ‘Marry with one’s match’, s/he might translate it literally or figuratively as ‘跟適合的人結婚’ (To marry the right person), ‘天生一對’ (Inborn couple), ‘門當戶對’ (A marriage between two persons with similar family backgrounds). When EFLLs encounter familiar idioms, they are capable of selecting the correct paraphrase (Flores d’Arcais, 1993). This proves that correct interpretation correlates highly with the familiarity with an idiom. Furthermore, most EFLLs use trial and error to find the meanings of the idioms, and heuristic methods such as analogy and using semantic properties to constitute the meaning of the lexical units to arrive at an appropriate or plausible interpretation (ibid). The comprehension of idioms is difficult for native or non-native speakers. EFLLs prefer to retrieve the figurative meaning of familiar idioms from memory, but need strategies to understand unfamiliar ones (Lin 2004).

Basic Principles for Cultural Translation of Idioms

Culture, idiom and translation are inseparable (Chen, 2009). Translation is a cultural creation. Thus, a cultural translator cannot only consider literary creation, but also cultural sentiments and aesthetics. According to Liu, Ming-Qing (2003), there are five attributes of cultural translation: meaning, emotion, force, beauty and style. ‘Meaning’ is communicated through the use of language. ‘Emotion’ can interact with biochemical (internal) and environmental (external) influences. ‘Force’ can produce the influence or effect. The experience of ‘beauty’ can provide us pleasure, meaning, or satisfaction. ‘Style’, is the outcome of a translator’s personality and emotions (Song et al., 2003).

Chen (2009) notes that a good translation also encompasses ‘essence’ (神韻) and ‘vividness’ (傳神). The ‘essence’ bears spiritual resemblance and the ‘vividness’ expresses appearance resemblance from the source language to target language. The translation of ‘Watch one’s step’ is ‘步步為營’ (Each step like in a barrack) retains its essence and vividness in TT (target text). In addition to preserving the attributes, remaining flexible is a feasible strategy to maintain the spiritual resemblance and semantic understanding of translated idioms. Beside the literal translation and free translation, naturalization, literal meaning with footnote and omission are ways to have an accurate cultural translation of idioms.

There is a longstanding dichotomy in translation studies between literal (or word-for-word) translation or free (sense-for-sense) translation (Galántai, 2002). A literal translation does not only retain the surface meaning, but also reproduces a source text’s meaning in another language. The idiom ‘Life is a dream’ is translated literally into ‘人生如夢’ which keeps the surface meaning. It is sometimes connoted ‘Life is but a dream’ and presents in Chinese characters. Galántai (2002) argues that translators must fall back on assumption about the original meanings of words when they are doing literal translation. When there is a failure to keep the original meaning, naturalization can be used. Naturalization is based on the cultural values and can maintain the ST’s original form. In other words, naturalization reduces the divergence between ST and TT and attempts to bring the author back home (Venuti, 1995/2008). The idiom ‘Fine feathers make fine birds’ is translated as ‘佛要金裝,人要衣裝’ (Buddha wears golden clothing, man wears an elegant dress) (lit.). The literal meaning of ST is related to birds and feathers, but Buddha and golden clothing are embedded in TT to expand the cultural value through naturalization. However, if a translator allows the readers to obtain more target texts, literal translation with footnotes might be a way to make translation understandable, especially to the source culture. This is a good means of cultural interchange (Chen, 2009). However, in order to facilitate readers’ comprehension with a cost-effective method of translation, omission of parts is appropriate. This method is a way to avoid difficult phrases. It can be used only for description, not for hands-on application (Chen, 2009).

Methods

Participants

One hundred and fifty-seven PTs were from two departments of the researcher’s classes at the National Kaohsiung University of Hospitality and Tourism in Taiwan. One was the Applied English Department (AED), the other was the Food and Beverage Department (F&BD). After eliminating the incomplete questionnaires, 150 usable questionnaires remained. Of these, 24% were from males and 84% were from females. About 71.3% were from AED and 28.7% from F&BD. Among the respondents, 78% used Mandarin Chinese at home, 8% spoke Taiwanese and 1.3% used Haganese, and 7.8% of PTs did not answer. More than half of PTs (53.9%) had never stayed in an English-speaking country (ESC) before. Only 4.5% had stayed in an ESC for one year and 1.6% had stayed for over 15 months. Of the respondents, 11.9% enjoyed studying linguistics and 11.5% were in the arts. The most popular pastimes were eating (14%) and traveling (11.1%).

Materials

The questionnaire consisted of three sections (see Appendix A). The first section was demographic information about gender, major, language spoken at home, time spent in English-speaking countries, favorite course, life preference, parents’ education, and parents’ occupation.

Ten English idioms in Section Two were designed as question items which were measured on a five-point Likert-type scale (1= extremely unfamiliar, 2=unfamiliar, 3= neutral, 4= familiar, 5=extremely familiar) at the beginning. However, when the contingency analysis between cultural experience and English idioms was conducted, many cells could not meet the 5% requirement, which influenced the statistical analysis. Thus, the five-point Likert scale was changed to a three-point scale. ‘Extremely unfamiliar’ was combined with ‘unfamiliar’ to become ‘unfamiliar’. ‘Extremely familiar’ was combined with ‘familiar’ to create ‘familiar’. ‘Neutral’ was unchanged. The statistical analysis benefited greatly from this combination.

Sampling and Data Collection Procedures

Convenience sampling was used in this exploratory research. Prior to finalizing the questionnaire, an interview and a pretest were used to revise the questionnaire. A formal questionnaire was given to 157 participants. Most PTs had a basic knowledge of translation and idioms. After the participants had been recruited, the researcher explained how to complete the questionnaires. After verifying the data three times, seven questionnaires were eliminated due to blatantly erroneous data, such as using the same scale to answer the questionnaires from the top question to bottom one or blanking out the questionnaires. Thus there were 150 usable questionnaires.

Data analysis

The collected data were analyzed by SPSS 17.0 based on the statistical procedures, which included (a) outputs of frequency and percentage of FEI for 10 texts; (b) an independent sample t-test to compare the mean scores of the different genders, departments and FEIs; (c) contingency analysis between cultural experience and English idioms; (d) the correlation coefficient employed to investigate the linear relationship among the variables; (e) outcomes of qualitative analysis related to cultural experience on 10 texts.

Findings

Outputs of Frequency and Percentage of FEI of 10 texts

Table 1 shows the frequency and percentage of FEIs. EI3, EI10 and EI6 were the lowest percentage of FEIs. The second lowest FEI were EI7, EI9 and EI2. Conversely, EI5 and EI7 were the two highest frequencies of FEIs. The results could remind teachers to deliver more instruction on idioms.

An Independent-Sample of T-test on Genders, Departments and FEIs

An independent – sample t-test was conducted to evaluate the hypothesis that different genders and departments had the same familiarity with English idioms for 10 texts. Table 2 (see Appendix 2) found that EI10 showed the mean score of males (M=2.50, SD=.780) was nearly statistically different (t=.968. p=.078) from that of female PTs (M=2.36, SD=.638). Though the output reflected that males got greater FEIs than females, Table 3 (see Appendix 3) presented the outputs of

Table 1 Frequency and Percentage of FEI

|

English Idioms |

Frequency |

Percentage |

||||||||

|

UNF |

NEU |

FAM |

TOTAL |

UNF |

NEU |

FAM |

TOTAL |

|||

|

EI 3.Hail the rising sun. |

117 |

25 |

7 |

149 |

78.5% |

16.8% |

4.7% |

100.0% |

||

|

EI 10.Man proposes and God disposes. |

108 |

27 |

15 |

150 |

72.0% |

18.0% |

10.0% |

100.0% |

||

|

EI 6.Our life is but a span. |

96 |

33 |

21 |

150 |

64.0% |

22.0% |

14.0% |

100.0% |

||

|

EI 1.Still waters run deep. |

76 |

42 |

32 |

150 |

50.7% |

28.0% |

21.3% |

100.0% |

||

|

EI 4.Marry with one's match. |

76 |

42 |

32 |

150 |

50.7% |

28.0% |

21.3% |

100.0% |

||

|

EI 8.Don't wash your dirty linen in public. |

75 |

40 |

34 |

149 |

50.3% |

26.8% |

22.8% |

100.0% |

||

|

EI5.Watch one's step. |

55 |

33 |

61 |

149 |

36.9% |

22.1% |

40.9% |

100.0% |

||

|

EI 2.Fine feathers make fine birds. |

50 |

43 |

56 |

149 |

33.6% |

28.9% |

37.6% |

100.0% |

||

|

EI 9.Every bird likes its own nest best. |

50 |

42 |

58 |

150 |

33.3% |

28.0% |

38.7% |

100.0% |

||

|

EI 7.Life is but a dream. |

46 |

43 |

60 |

149 |

30.9% |

28.9% |

40.3% |

100.0% |

||

※EI=English idiom; FEI=familiarity with English idioms; UNF=unfamiliar /

NEU=neutral / FAM=familiar

the t-test procedure to demonstrate a statistically significant difference between FEI and departments. The mean scores of EI6, EI8, EI9 and EI10 of AED (M=2.63, SD=.795) (M=2.88, SD=.832) (M=3.33, SD=.762) (M=2.44, SD=.703) were statistically different (t=3.458, p=.000) (t=3.853, p=.002) (t=7.212, p=.024) (t=1.740, p=.001) from that of F&BD (M=2.19, SD=.394) (M=2.33, SD=.612) (M=2.37, SD=.655) (M=2.23, SD=.527). The outputs of EI6, EI8, EI9 and EI10 indicated that PTs whose major was Applied English had more FEIs than the PTs whose major was Food and Beverage. The results of the t-test rejected the null hypothesis of research question 2, meaning that there were different FEIs between males and females, and between AED and F&BD.

Contingency Analysis between Cultural Experience and English Idioms

Table 4 was concerned with a statistically significant difference (Pearson Chi-Square=2349.482,df= 63,p =0.000<0.05) between cultural experience and English idioms. There was an expected count in one cell (1.3%) less than 5. It was meaningless to integrate the cells resulting from the lower frequency; the minimum expected count was near 5 and not hugely different to the adjacent categories. Nonetheless, there was no integration of cells; the results were statistically reliable. Upon further exploration, additional findings were made.

Table 4 Contingency Analysis between Cultural Experience and English Idioms

|

EI CE |

EI1 |

EI 2 |

EI 3 |

EI 4 |

EI 5 |

EI 6 |

EI 7 |

EI 8 |

EI 9 |

EI 10 |

Total |

|

|

1.SOC |

FRE |

22 |

36 |

13 |

7 |

45 |

6 |

7 |

21 |

7 |

7 |

171 |

|

EP(%) |

17.9 |

16.9 |

14.9 |

18.3 |

16.2 |

17.5 |

18.4 |

17.3 |

18.0 |

15.5 |

171 |

|

|

RPER(%) |

12.9 |

21.1 |

7.6 |

4.1 |

26.3 |

3.5 |

4.1 |

12.3 |

4.1 |

4.1 |

100 |

|

|

2.MOR |

FRE |

22 |

10 |

13 |

2 |

20 |

2 |

2 |

54 |

4 |

8 |

137 |

|

EP(%) |

14.3 |

13.6 |

11.9 |

14.7 |

13.0 |

14.0 |

14.8 |

13.9 |

14.4 |

12.5 |

137 |

|

|

RPER(%) |

16.1 |

7.3 |

9.5 |

1.5 |

14.6 |

1.5 |

1.5 |

39.4 |

2.9 |

5.8 |

100 |

|

|

3.MAR |

FRE |

1 |

0 |

1 |

117 |

3 |

5 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

131 |

|

EP(%) |

13.7 |

13.0 |

11.4 |

14.0 |

12.4 |

13.4 |

14.1 |

13.3 |

13.8 |

11.9 |

131 |

|

|

RPER(%) |

0.8 |

0.0 |

0.8 |

89.3 |

2.3 |

3.8 |

0.8 |

0.8 |

0.0 |

1.5 |

100 |

|

|

4.LIFE |

FRE |

52 |

26 |

46 |

1 |

27 |

105 |

117 |

6 |

8 |

28 |

416 |

|

EP(%) |

43.5 |

41.2 |

36.1 |

44.5 |

39.5 |

42.5 |

44.8 |

42.2 |

43.8 |

37.8 |

416 |

|

|

RPER(%) |

12.5 |

6.3 |

11.1 |

0.2 |

6.5 |

25.2 |

28.1 |

1.4 |

1.9 |

6.7 |

100 |

|

|

5.WEA |

FRE |

13 |

12 |

12 |

0 |

6 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

5 |

3 |

56 |

|

EP(%) |

5.9 |

5.5 |

4.9 |

6.0 |

5.3 |

5.7 |

6.0 |

5.7 |

5.9 |

5.1 |

56 |

|

|

RPER(%) |

23.2 |

21.4 |

21.4 |

0.0 |

10.7 |

1.8 |

3.6 |

3.6 |

8.9 |

5.4 |

100 |

|

|

6.FAM |

FRE |

1 |

31 |

3 |

4 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

36 |

97 |

4 |

180 |

|

EP(%) |

18.8 |

17.8 |

15.6 |

19.3 |

17.1 |

18.4 |

19.4 |

18.2 |

19.0 |

16.4 |

180 |

|

|

RPER(%) |

0.6 |

17.2 |

1.7 |

2.2 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

0.0 |

20.0 |

53.9 |

2.2 |

100 |

|

|

7.REL |

FRE |

4 |

0 |

11 |

1 |

1 |

4 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

58 |

84 |

|

EP(%) |

8.8 |

8.3 |

7.3 |

9.0 |

8.0 |

8.6 |

9.1 |

8.5 |

8.9 |

7.6 |

84 |

|

|

RPER(%) |

4.8 |

0.0 |

13.1 |

1.2 |

1.2 |

4.8 |

3.6 |

1.2 |

1.2 |

69.0 |

100 |

|

|

8.OTH |

FRE |

15 |

8 |

9 |

1 |

14 |

2 |

2 |

5 |

9 |

3 |

68 |

|

EP(%) |

7.1 |

6.7 |

5.9 |

7.3 |

6.5 |

6.9 |

7.3 |

6.9 |

7.2 |

6.2 |

68 |

|

|

RPER(%) |

22.1 |

11.8 |

13.2 |

1.5 |

20.6 |

2.9 |

2.9 |

7.4 |

13.2 |

4.4 |

100 |

|

|

Total |

FRE |

130 |

123 |

108 |

133 |

118 |

127 |

134 |

126 |

131 |

113 |

1243 |

|

EP(%) |

130 |

123 |

108 |

133 |

118 |

127 |

134 |

126 |

131 |

113 |

1243 |

|

|

RPER(%) |

10.5 |

9.9 |

8.7 |

10.7 |

9.5 |

10.2 |

10.8 |

10.1 |

10.5 |

9.1 |

100 |

※FRE=Frequency; EP=Expected Percentage; RPER=Row Percentage; 1 cell (1.3%) has expected count

less than 5. The minimum expected count is 4.87. Pearson Chi-Square=2349.482,df= 63,p =0.000<0.05,

N =1243; SOC=social, MOR=moral, MAR= marriage, WEA=wealth, FAM=family, REL=religion, OTH=others.

- The highest percentage was the 26.3% of EI5 which belonged to ‘society’. The next highest percentage was the 21.1% of answer EI2. The answers EI4, EI9 and EI10 were 4.1%, the lowest percentage. Presumably, a high frequency of PTs categorized EI2and EI5 into ‘society’ based on their cultural experience when they translated English idioms into their Chinese equivalents.

- The highest percentage was the 39.4% of EI8 as ‘moral’, and the second-highest frequency (16.1%) of PTs classified EI1 as ‘moral’. EI4, EI6 and EI7 at 1.5% were the lowest percentage. The highest percentage of PTs treated EI8 and EI1 as ‘moral’ category.

- The highest percentage (89.3%) specified EI4 as ‘marriage’. However, only five PTs finished classifying the other items into proper cultural aspects. This might have resulted from the word ‘marry’ appearing in this idiom to lead most PTs to identify EI4 with ‘marriage’.

- The highest percentage of PTs (28.1) treated EI7 and EI6 (25.2%) as ‘life’. In contrast, 0.2%, 1.4% and 1.9% of PTs agreed that the idiomatic translation of EI4, EI8 and EI9 could be categorized into ‘life’. Presumably, the word ‘life’ in EI6 and EI7 persuaded most PTs to classify them as a cultural aspect of ‘life’.

- The highest percentage (23.2%) of PTs classified EI1 into ‘wealth’, and 12 (21.4%) was the second highest percentage to specify EI2 and EI3 as ‘wealth’. None of the PTs regarded EI4 as ‘wealth’. From the analysis above, the frequency of answering EI1, EI2 and EI3 was lower. This might result from PTs who had difficulty comprehending these idioms or they might have had insufficient cultural experience.

- With respect to EI9, the highest percentage (53.9%) of PTs agreed that this item could be categorized as ‘family’. EI8 (20.0%) and EI2 (17.2%) were the second and third highest percentages. Overall, most PTs treated EI9, EI8 and EI2 as ‘family’ based on their cultural experience. Presumably, a phrase such as ‘washing linen’ (extended to mean ‘a house cleaning job’) and ‘nest’ (the metaphorical meaning of ‘home’ in Chinese culture) influenced the PTs’ cultural judgment.

- Up to 69% of PTs specified EI10 as ‘religion’, while 13.1% of PTs treated EI3 as ‘religion’. Yet a very low frequency of PTs classified answers into the category of ‘others’. A high frequency of PTs regarded EI10 as ‘religion’; this apparently was influenced by the reference to ‘God’ in this idiom.

- As for the last cultural aspect-‘others’, the 22.1% of EI1 was the highest, while EI5 (20.6%) was the second highest percentage. The answers given by PTs were influenced by the obscurity of the SL.

Correlation Coefficients of FEI for Variables

The correlation coefficient (r) represented the linear relationship between two variables and indicated the degree or direction of correlation (i.e., the ‘high’ or ‘low’ and ‘positive’ or ‘negative’) for the variables. This could not be interpreted to mean that the independent variables affected the dependent variables. The positive or negative value of the correlation coefficient demonstrated the related direction, and used

Table 5 Spearman’s Rank Correlation Coefficient of FEI

|

EI1 |

EI2 |

EI3 |

EI4 |

EI5 |

EI6 |

EI7 |

EI8 |

EI9 |

|

|

EI1 |

|||||||||

|

EI2 |

0.440 |

||||||||

|

EI3 |

0.344 |

0.367 |

|||||||

|

EI4 |

0.300 |

0.227 |

0.414 |

||||||

|

EI5 |

0.409 |

0.406 |

0.285 |

0.354 |

|||||

|

EI6 |

0.397 |

0.460 |

0.461 |

0.391 |

0.406 |

||||

|

EI7 |

0.366 |

0.517 |

0.330 |

0.309 |

0.500 |

0.581 |

|||

|

EI8 |

0.237 |

0.409 |

0.237 |

0.247 |

0.225 |

0.372 |

0.497 |

||

|

EI9 |

0.398 |

0.494 |

0.220 |

0.337 |

0.416 |

0.508 |

0.577 |

0.561 |

|

|

EI10 |

0.369 |

0.233 |

0.405 |

0.422 |

0.230 |

0.370 |

0.308 |

0.418 |

0.397 |

- P values above were less than .01, so were avoided being repeated.

- Listwise N=144

- Code names: EI1.Still waters run deep.EI2.Fine feathers make fine birds.EI3.Hail the rising sun. EI4.Marry with one’s match. EI5.Watch one’s step. EI6.Our life is but a span. EI7.Life is but a dream.EI8.Don’t wash your dirty linen in public. EI9.Every bird likes its own nest best. EI10.Man proposes and God disposes.

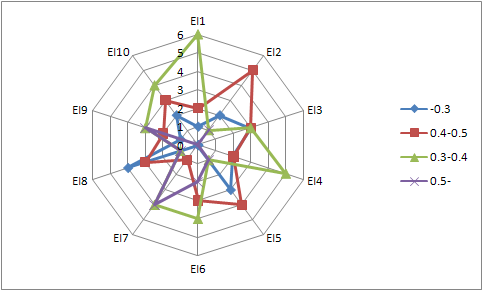

Fig. 1:Spearman's Rho Rank Correlation Coefficient of FEI

the value of ‘r’ to indicate the degree of correlation. While the r value between 0.3 and -0.3 represented the low correlation, between 0.3 and 0.7 or -0.3 and -0.7 it was treated as a medium correlation. As for the high correlation, the r value was between 0.7 and 0.9 or -0.7 and -0.9. An r value of +1 or -1, reveals complete correlation. As if the data were the variables of interval scales, it was essential to select Pearson’s product-moment correlation coefficient. Alternatively, if the data were the variables of ordinal scales Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was used. The outcomes of recognition of Pearson’s product-moment correlation coefficient were similar to Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. The Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient of FEI was presented in Table 5. The highest Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient out of all the English idioms was EI7 (‘Life is but a dream’) (see Table 5 and Fig.1). In addition, the Spearman’s values of EI2, EI5 and EI6 were greater than 0.5, indicating a moderate and positive correlation among these idioms. This corresponded to the high FEI of EI7, which retained high FEIs with EI2, EI5 and EI6 simultaneously. Conversely, the low FEI of EI7 might lead to the same low influence on EI2, EI5 and EI6. This presumably resulted from sharing a cultural experience of birds, life and dreams. However, the Spearman’s value of EI8 (‘Don’t wash your dirty linen in public’) was lowest at less than 0.3 with EI1 (0.237), EI3 (0.237), EI4 (0.247) and EI5 (0.225). This indicated these values shared similar linguistic attributes with a low positive correlation.

Outcomes of Qualitative Analysis Related to Cultural Experience on 10 Texts

Table 6 (see Appendix 4) is concerned with the different translations of an English idiom, ‘Still waters run deep’ (EI1), with its Chinese equivalents (CEs) as follows:

|

深藏不露(One tries to hide oneself) (14/18.4%) (Frequency/Percentage) |

|

大智若愚 (The wise man appears like a fool) (12/15.8%) |

|

細水長流 (Small streams flow longer) (8/10.5%) |

|

滴水穿石 (Drips of water wear through a stone) (7/9.2%) |

|

水往深(低)處流 (Water goes to a deep place) (7/9.2%) |

|

深不可測 (Depth cannot be measured) (6/7.9%) |

Not all PTs were able to provide CEs for each English idiom when they answered the questionnaires, thus 76 CEs for EI1 were collected. The top six frequencies of CEs were shown to decrease. Interestingly, the top two highest percentages of CEs, ‘深藏不露’ and ‘大智若愚’, were ‘Still waters run deep’ from Chinese Idioms and Their English Equivalents (Chen et al.,1998). Yet, the CE of ‘水往深(低)處流’ was presented by 7 PTs who translated it literally as ‘Water goes to a deep place’. The Chinese characters of ‘深’ (deep or depth) and ‘水’ (water) were given in CEs. Only a CE of ‘大智若愚’ was irrelevant to linguistic attributes of ‘deep’ (or ‘depth’) or ‘water’.

The CE of ‘Fine feathers make fine birds’ (EI2) was ‘佛要金裝,人要衣裝’ (Buddha wears golden clothing, man wears an elegant dress) (lit.). Eighteen PTs gave the translation as the CE above; they classified the CEs into ‘society’ from their cultural experience. Three PTs regarded this CE as ‘life’ and two answered with ‘wealth’. Interestingly, the next highest frequencies of CE were ‘物以類聚’ (Things of the same kind get together) (lit.) (14 PTs) and ‘工欲善其事,必先利其器。’ (A workman wishing to do good work must first sharpen his tools) (lit.) (15 PTs). Most PTs categorized these CEs into ‘society’ and ‘life’. The CE of ‘有其父必有其子’ (Having such a father must have such a son) (lit.) was provided by ten PTs and classified into ‘family’.

The CE of ‘Hail the rising sun’ (EI3) was ‘趨炎附勢’ (Follow the flame and join the influential) (lit.). Only one PT translated it as the CE above, while many PTs translated it into ‘一日之計在於晨’ (A day’s plan starts from morning) (lit.) and categorized it as ‘life’. The second highest frequencies of CEs were ‘旭日東昇’ (Sun rises from east) (lit.) and ‘撥雲見日’ (Sweep the cloud away to see sun) (lit.). One word from two CEs was related to the Chinese character ‘日’ (sun), which was translated literally and linked with the English word ‘sun’. Likewise, two CEs described this idiom as ‘日出而作’ (Sun rises and go out to work) (lit.) and ‘日正當中’ (Sun appears at noon) (lit.), which related to ‘sun’ too. We might say that the individual word from the idiom could establish a strong link for the PTs to classify CEs into different cultural aspects.

The idiom ‘Marry with one’s match’ (EI4) (門當戶對) (The doors of both sides are well matched) (lit.) was translated as ‘天作之合’ (Heaven makes the union) and ‘天生一對’ (Heaven bears one pair) by PTs. Two CEs showed high frequency of the cultural aspect of ‘marriage’. Furthermore, various CEs were explored by PTs such as ‘情投意合’ (To hit it off perfectly), ‘嫁雞隨雞’ (Marry a rooster and follow it ) and ‘有情人終成眷屬’ (Lovers become a family). These CEs were classified as ‘marriage’ accordingly. Fourteen types of CE were provided for EI4 to indicate that this idiom inspired PTs to find various CEs.

‘Watch one’s step’ (EI5) (慎言謹行) (Cautious word, careful action) (lit.) was translated as ‘步步為營’ (To consolidate at every step) (lit.) with the highest frequency, but numerous cultural aspects were given, such as ‘society’ (15 PTs), ‘life’ (7),‘moral’ (3), ‘others’ (3), ‘marriage’ (1) and ‘religion’ (1). Likewise, some CEs linked with the word ‘watch’ and translated as ‘小心翼翼’ (with exceptional caution) (lit.) and ‘小心謹慎’ (careful and discreet) (lit.).

Several CEs of ‘Our life is but a span’ (EI6) were presented as ‘人生苦短’ (Life is short and painful) (lit.), ‘人生如戲’ (Life is like a play) (lit.), ‘人生虛度’ (Life is like spending in vain) (lit.) and ‘曇花一現’ (A night-blooming cereus shows one time) (lit.). The former three CEs were linked with the word ‘life’, which influenced PTs to provide the same CE and categorized them into ‘life’. Eleven types of CE were collected and classified into ‘life’. Similarly, the idiom ‘Life is but a dream’ (EI7) was translated as ‘人生如夢’(Life like a dream) (lit.) and was listed as ‘life’ with the greatest frequency (43) from PTs.

Three CEs for EI8 (Don’t wash your dirty linen in public) were ‘別自暴其短’ (Don’t display your shortcomings) (lit.), ‘家醜不外揚’ (The family disgrace is not waved outside) (lit.) and ‘別自取其辱’ (Don’t pick up humiliation) (lit.) provided by PTs. This indicated that the most PTs reached a consensus on CEs. Seventy percent of PTs agreed with the CE of ‘家醜不外揚’ and 27% tended to the CE of ‘別自暴其短’. Both CEs were categorized into the cultural experience of ‘family’ with high frequency, probably because the collocation of ‘dirty linen’ links semantically with the concepts of ‘bedroom’ and ‘house’.

Five CEs for EI9 (Every bird likes its own nest best) were presented in response, showing a lack of consensus among PTs. More than half of PTs (55%) pointed out EI9 as ‘金窩銀窩不如自己的狗窩’ (Golden den or silver den is not better than own doghouse) (lit.) and they reported EI9 as belonging to ‘family’ to link with the literal meaning of ‘nest’ from the Chinese character ‘巢’ (i.e. ‘home’ or ‘house’). The second highest frequency of CE (31%) was ‘愛鳥及屋’ (Love bird loves its nest) (lit.). However, few categories of cultural experience reached a high consensus for EI9.

Highly different CEs for EI10 (Man proposes and God disposes) showed many different opinions on this EI, including ‘事與願違’ (The fact contravenes the wish) (lit.), ‘人算不如天算’ (Men’s calculation is not as good as that of heaven) (lit.), ‘聽天由命’ (Let Heaven and fate decide) (lit.) and ‘人定勝天’ (With determination men conquer nature) (lit.), in decreasing order of frequency. Interestingly, ‘天’ was regarded as ‘God’ or ‘heaven’ and ‘人’ was explained as ‘man’, with semantic relationship to above-mentioned CEs. Despite many different CEs, only the cultural aspects of ‘life’ and ‘religion’ were accepted by most PTs.

Conclusions

In summary, these findings are consistent with those of previous studies that suggest the profound influence of culture upon translation. Accordingly, the results of t-test achieved a statistically significant difference among genders, departments and FEIs. This verified that different variables could influence FEIs. Furthermore, there was a statistically significant difference between cultural experience and English idiom categories. Apparently, the more cultural experience the PTs had, the more competence with English idioms they gained. In addition, the results of correlation coefficients showed a high FEI from a PT who could retain a high FEI for the other English idioms. The outcomes of qualitative analysis indicated the ways in which the variance of translation was provided by PTs. Very often a high frequency of PTs were influenced by the literal meaning of EIs while they were providing CEs for EIs, and then categorized them according to their cultural aspects. A high frequency of PTs reached consensus on EI3, EI5, EI6, EI7 and EI8, and shared a cultural experience. Since these participants were from two different departments, these results cannot be applied to other EFL learners. Furthermore, 10 texts was too small a sample to provide a broad scope of SL. On these bases, more participants and texts should be involved in future studies. In addition, the cluster or factor analysis on FEIs is a topic that merits investigation into what aspects influence FEIs for EFL learners. The results of prospective study may help teachers and EFL learners to adopt more effective methods of teaching and learning translation of cultural idioms.

References

Chen, Y.C., & Chen, S.T. (1998). Chinese idioms and their English equivalents.

Bookman Publishing.

Chen, Y.Y. (2009). A study on translation strategy of Chinese cultural terms:

toward an analytic framework. Unpublished master’s thesis, National Yunlin

University of Science & Technology.

Cooper, T.C. (1999). Processing of idioms by L2 learners of English.

TESOL Quarterly, 33, 233-262.

Creswell, J.W. (2009). Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods

approaches. Sage Publications.

Fan, M. (2007). Cultural issues in Chinese idioms translation. Perspectives, 15:4,

215-229.

Faull, K.M. (ed.) (2004). Translation and culture. Bucknell University Press.

Flores d’Arcais, G.B. (1993). The comprehension and semantic interpretation of

idioms. In C. Cacciari & P. Tabossi (Eds.), Idioms: Processing, structure, and interpretation (pp.79-98). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Galántai, D. (2002). Literal meaning in translation. Perspectives, 10: 3, 167-192.

Gibbs, R.W. (1999). The poetics of minds. Cambridge University Press.

Lin, Y.P. (2004). EFL learners’ processing of unknown idioms. Unpublished master’s

thesis, National Kaohsiung Normal University.

Song, X.S., & Chen, D.M. (2003). Translation of literary style. Translation

Journal,7(1), Retrieved from http://translationjournal.net/journal/23style.htm

Venuti, L. (1995/2008). The translator’s invisibility: A history of translation.

London and New York: Routledge.

Wu, M.C. (2004). A macro-linguistic study of Taiwanese proverbs and their humour.

Unpublished doctoral dissertation. School of Education, University of Leicester,

UK.

Wu, M.C. (2011). Translation: A multidimensional approach – theories and applications. Taiwan: Bookman Books Co. Ltd.

劉宓慶 (Liu, Ming-Qing). (2003). 翻譯教學:實務與理論. 北京:中國對外翻

譯出版公司.

葉子南(Ye, Zi-Nan). (2000). 英漢翻譯理論與實踐, 6.台北:書林.

Appendices

Appendix 1 Sample Page of Questionnaire

Part A: Questionnaire of Familiarity with English Idioms

Instructions for answering questionnaire: Please circle one answer.

1= Unfamiliar (UFA) 2=Neutral (NEU) 3= Familiar (FAM)

|

No. |

English Idiom |

UFA |

NEU |

FAM |

|

1 |

Still waters run deep. |

|||

|

2 |

Fine feathers make fine birds. |

|||

|

3 |

Hail the rising sun. |

|||

|

4 |

Marry with one’s match. |

|||

|

5 |

Watch one’s step. |

|||

|

6 |

Our life is but a span. |

|||

|

7 |

Life is but a dream. |

|||

|

8 |

Don’t wash your dirty linen in public. |

|||

|

9 |

Every bird likes its own nest best. |

|||

|

10 |

Man proposes and God disposes. |

Appendix 2 Table 2 The Outputs of Gender and FEI with 10 Texts

|

Item |

Gender |

N |

Mean |

SD |

t |

p |

|

EI1 |

F |

126 |

2.71 |

.811 |

.011 |

.309 |

|

M |

24 |

2.71 |

.751 |

|||

|

EI2 |

F |

126 |

3.08 |

.845 |

-1.325 |

.896 |

|

M |

23 |

2.83 |

.834 |

|||

|

EI3 |

F |

126 |

2.27 |

.559 |

-.530 |

.209 |

|

M |

23 |

2.21 |

.415 |

|||

|

EI4 |

F |

125 |

2.67 |

.821 |

.199 |

.665 |

|

M |

24 |

2.71 |

.806 |

|||

|

EI5 |

F |

126 |

3.05 |

.884 |

-.237 |

.970 |

|

M |

23 |

3.00 |

.905 |

|||

|

EI6 |

F |

126 |

2.52 |

.735 |

-.609 |

.470 |

|

M |

24 |

2.42 |

.717 |

|||

|

EI7 |

F |

125 |

3.13 |

.842 |

-1.129 |

.566 |

|

M |

24 |

2.92 |

.830 |

|||

|

EI8 |

F |

125 |

2.73 |

.817 |

.108 |

.747 |

|

M |

24 |

2.71 |

.806 |

|||

|

EI9 |

F |

126 |

3.08 |

.864 |

-.859 |

.108 |

|

M |

24 |

2.92 |

.776 |

|||

|

EI10 |

F |

126 |

2.36 |

.638 |

.968 |

.078 |

|

M |

24 |

2.50 |

.780 |

※ F=Female M=Male FEI=Familiarity with English idiom

Appendix 3 Table 3 The Outputs of Departments and FEI with 10 Texts

|

Item |

Dept. |

N |

Mean |

SD |

t |

p |

|

EI1 |

App E |

107 |

2.77 |

.819 |

1.449 |

.204 |

|

F&B |

43 |

2.56 |

.734 |

|||

|

EI2 |

AED |

107 |

3.21 |

.821 |

3.999 |

.455 |

|

F&BD |

43 |

2.62 |

.764 |

|||

|

EI3 |

AED |

107 |

2.28 |

.582 |

.757 |

.071 |

|

F&BD |

43 |

2.21 |

.412 |

|||

|

EI4 |

AED |

107 |

2.72 |

.822 |

.997 |

.616 |

|

F&BD |

43 |

2.57 |

.801 |

|||

|

EI5 |

AED |

107 |

3.18 |

.867 |

3.112 |

.671 |

|

F&BD |

43 |

2.69 |

.841 |

|||

|

EI6 |

AED |

107 |

2.63 |

.795 |

3.458 |

.000 |

|

F&BD |

43 |

2.19 |

.394 |

|||

|

EI7 |

AED |

107 |

3.26 |

.796 |

4.078 |

.835 |

|

F&BD |

43 |

2.67 |

.808 |

|||

|

EI8 |

AED |

107 |

2.88 |

.832 |

3.853 |

.002 |

|

F&BD |

43 |

2.33 |

.612 |

|||

|

EI9 |

AED |

107 |

3.33 |

.762 |

7.212 |

.024 |

|

F&BD |

43 |

2.37 |

.655 |

|||

|

EI10 |

AED |

107 |

2.44 |

.703 |

1.740 |

.001 |

|

F&BD |

43 |

2.23 |

.527 |

※ AED=Applied English Department F&BD=Food and Beverage Department

Appendix 4 Table 6 The translation of the English idiom ‘Still waters run deep’

|

EI 1 Still waters run deep. (虛懷若谷) |

|||

|

Chinese Translation (CT) |

Frequency (Percentage) |

Remarks |

|

|

1 |

深藏不露 |

14 (18.4%) |

Lit: One tries to hide oneself. Ene: Still waters run deep. |

|

2 |

大智若愚 |

12 (15.8%) |

Lit: The wise man appears like a fool. Ene: Still waters run deep. |

|

3 |

細水長流 |

8 (10.5%) |

Lit: Small streams flow long. Ene: A bit at a time. |

|

4 |

滴水穿石 |

7 (9.2%) |

Lit: Drops of water wear through a stone. Ene: Slow but sure wins the race. |

|

5 |

水往深(低)處流 |

7 (9.2%) |

Lit: Water runs deep place. Ene: Nil |

|

6 |

深不可測 |

6 (7.9%) |

Lit: Depth cannot be measured. Ene: Unfathomable |

|

7 |

好酒沉甕底 |

4 (5.3%) |

Lit: Good wine stays in the bottom. Ene: Good things come at the end. |

|

8 |

源源不絕 |

2 (2.6%) |

Lit: Fountful water without termination. Ene: Endless |

|

9 |

水到渠成 |

2 (2.6%) |

Lit: Water comes a canal is built. Ene: Don’t cross a bridge until you come to it. |

|

10 |

水深火熱 |

1 (1.3%) |

Literal meaning (Lit.): Water deep and fire hot. Ene: To be in deep water. |

|

11 |

靜水深流 |

10 (13.2%) |

Lit: Quiet water run deep. Ene: Nil |

|

12 |

滾石成金 |

1 (1.3%) |

Lit: Rolling water becomes a gold. Ene: Nil |

|

13 |

人不可貌相 |

1 (1.3%) |

Lit: A man cannot be judged by his looks. Ene: Never judge from appearances. |

|

14 |

鍥而不捨 |

1 (1.3%) |

Lit: Would not give up the engraving. Ene: Firm and unyielding. |

|

Total |

76 (100%) |

||

*Lit=literal Ene=English equivalent