October 2017 Issue

Read, Comment and Enjoy!

Join Translation Journal

Click on the Subscribe button below to receive regular updates.

Error Evaluation in the Teaching of Translation: A Corpus-based Study

- Details

- Written by Ramadan Ahmed Almijrab

Although different criteria have been proposed in applied translation literature in order to eliminate the subjectivity of the instructor/evaluator, these attempts remain tentative and, consequently, evaluation is still an area of controversy. The purpose of this corpus-based study is to demonstrate an integrated learning environment set up to provide students with constructive and more objective feedback on their translations and to evaluate their production within the framework of corpus project meant as a tool for instructors’ translation quality assessment. I have tried to predict different possible criteria instructors might be using during their evaluation of the students translation errors, viz. frequency, generality, intelligibility, interpretation, and naturalness. To achieve this end, the study investigates the inter- and intra-consistency and reliability of the instructors' assessment of the students’ errors within the framework of these criteria. I shall concern myself with issues related to the evaluation of instructors’ assessment tools and criteria and their implications for a successful training programme.

Keywords: error analysis, consistency, translation, error evaluation.

1. Introduction

Research in the field of translation quality assessment has achieved no consensus in introducing the assessment criteria used in evaluating students' translations. O'Brien(2012: 1)states that “one of the dominant current methods for translation quality evaluation within the translation industry, i.e. the error typology, is seen as being static and unable to respond to new text types or varying communicative situations and this is leading to rising levels of dissatisfaction”. This is because translation is a multifaceted process which involves other problems than language bound ones including terms of context, readership, topics and so forth which are more extended and not at the disposal of the translators. Accordingly, translation evaluation has become more challenging for instructors/evaluators who have to sense and generalize about the quality of the obscure aspects.

I find it useful to stretch a point by saying that the focus here is not on the theory of translation quality assessment, nor on its implementation in translator training, but rather on the practice of translation quality evaluation in the professional sphere where translation quality is also ever topical and contentious. Therefore, the basic principle behind this classification of errors is the type of negative effect to the target text (TT) quality caused by translation students’ renderings. They can either be inappropriate in terms of content transfer or in terms of target language (TL) expression, i.e. it is the TT, which is the object of evaluation, and the major criterion of evaluation is the relations between source text (ST) and TT.

First and for most, students' translation errors must be identified because "instructors are relieved when students respond to the test items correctly. However, if the student does not answer an item correctly, the instructor must analyse further and investigate whether the incorrect answer a mistake indicates a fault in performance, i.e. not systematic” (Goff-Cfouri 2014: 2). For this, it seems necessary that instructors should make an accurate critical analysis of the students' translations in order to be able to detect errors. In describing the detected errors, instructors should try to see in what way the students have failed to communicate or transfer the original message by comparing the ST and the students’ target product. Then, they will have to explain how students have deviated from an adequate translation and what rules they have broken. Kiraly 2000: 140) advises us

if we expect our assessments, marks and evaluations to provide valuable information about students’ learning progress to teachers, future employers and the students themselves, then our assessments (i.e. information collection) procedures must be (1) demonstrably based on deep and extensive observation of students’ performance; (2) representative of the conditions and standards under which our graduates can expect to work professionally; and (3) equitable and collaborative, with students taking an active, empowered role in the assessment process.

This means that instructors should adopt evaluative measures and seek appropriate pedagogical assistance.

In translation studies, different evaluation methods are currently being used and developed which aim to improve translation pedagogy, but they still facing some obstacles. In this domain, Pym (1992: 279) argues that

empirical evaluations of translation teaching and learning are generally hampered by the complexity of the many fields involved, the subjectivity of the assessment methods used and the difficulty of obtaining representative samples and control groups. These factors tend to restrict clear results to very basic linguistic levels, and even then the interpretation of results requires a mostly lacking idea of what translation is, to what precise end it should be taught and exactly what effects empirical research can have on its teaching.

However, assessment of translation error is not an undisputed issue in translation studies. The main problem seems to lie in how to assess the quality or what measures should be used to evaluate the translation. The measures used will be different, depending on the purpose of the assessment and on the theoretical framework applied to assessing the translation quality.

2. Possible Criteria for Evaluation

It is undeniable fact that evaluation is not an easy task because the requirement or ideal aim is to produce the objective out of the subjective. A sound evaluation should go beyond intuition to achieve objectivity and accuracy (Kupsch-Losereit 1985). In translation practice, however, the operation inevitably involves the making of personal judgements and cannot be a pure mechanical process. Instructors are required to seek a basis for informed judgement built upon both theoretical consideration and experimental criteria. In this respect, an attempt has been made to discuss the main criteria, namely, frequency, generality, intelligibility, interpretation, and naturalness, to see how far they serve this purpose. It remains to be added that the criteria at hand are borrowed mainly from literature on foreign language teaching (Davies 1982) and translation quality assessment (House 1997, Almijrab 2013).

2.1 The Frequency Criterion

This criterion assesses errors in terms of the number of their occurrence, i.e. quantitative. The majority of translation instructors would opt for a quality assessment as translation involves a transfer of meaning which can be affected by the quality of the error rather than its quantity. Yet, a high distribution of an error can always alarm instructors and arouse their doubts, especially when it is widespread among various students. As far as frequency criterion is concerned, two different ways for assessing the relative gravity of the error can be distinguished. The first relates the gravity of the error to its frequency in the work of the same individual student. Obviously, this procedure is not often easy to be achieved by the instructor who normally cannot single out every individual error because of economy of time and effort. That is, the instructor cannot, in addition to determining the distribution of each student's errors, design re-teaching methods for each student. This is not indeed a practical goal if we take into account the fact that, because of shortage of time, the instructor has to satisfy the needs of different classes rather than individual students. The second is more likely to be of interest to our target instructors as it concerns the frequency of errors within a group of students, the most recurrent being the most serious. It is not surprising that most errors falling within the parameters of this criterion have been heavily penalised.

Corrective measures are to be initiated depending on the type and the source of error. In other words, the error is assessed in terms of its situation of occurrence because the same error can occur in different translated texts but may affect the quality of the translations differently. Translation errors should therefore be judged accordingly, depending on their situation of occurrence. For instance, the Arabic translation of the sentence he is studying linguistics is yadrusu al-lugha (he is studying the language) this could be acceptable for a nonprofessional in the field of language and linguistics although we recognise the wrong selection of the term لغة (language) instead of al-lisa:niya:t (linguistics). On the contrary, in a situation where distinction between language and linguistics is essential to the meaning of the text, the error can be regarded as serious.

2.2 The Generality Criterion

The generality criterion implies that the acquisition of lexis is a less fundamental skill for the translator than the mastery of grammatical structures. Thus, the evaluation should be performed in terms of the major/minor rules infringed, the more general being the more serious. Major errors refer to those failures to observe general grammatical rules such as case inflections in Arabic, or the insertion of the appropriate tense like the infinitive after a conjugated verb in English. On the other hand, minor errors refer to failures to observe exceptions to major rules which most often result in overgeneralisation.

In crude terms, the criterion considers grammatical errors more serious than lexical ones as error gravity is determined in terms of the syntactic structures they violate. Norish (1983) distinguishes in this respect between two types of error. The first, involves local errors, which are evaluated as less serious since they involve single lexical items which are unlikely to affect the entire understanding of the message. The second involves global errors which occur in main clauses and are likely to affect the meaning of the whole message. This claim of this nature might be less useful in translation quality assessment because an error relating to a single lexical item can be more detrimental to the meaning of a message than breaking the general grammatical rule at sentence level.

2.3 The Intelligibility Criterion

The intelligibility criterion, however, holds that we are more likely to be comprehensible with the help of words without syntax than with syntactic structures without words. That is, the communicative goal of a text is more seriously affected if the errors involve wrong selection of words rather than the violation of syntactic structure. Accordingly, lexical errors can affect the intelligibility of the translation in two different ways: first, by making the intended message totally unintelligible and thus causing a breakdown in the communicative function of the text; and second, by distorting the meaning without impairing communication, so that the TL reader understands something other than the original author's intention. The importance of this criterion to our analysis lies in the fact that it determines how instructors differently assess distortion of meaning and disruption of communication. For instance, the translation of the Hadith (sayings and deeds of the prophet Muhammad) al-yad al-Culya: khayr min al-yad al-sufla is likely to be unintelligible to an English reader if translated literally, as the upper hand is better than the lower hand. The reader however is likely to associate the upper hand with power and authority which is completely different from the ST intended meaning: the giving hand is better than the receiving hand.

We would therefore expect instructors to conceive different levels of seriousness in their assessment of intelligibility errors rather than be confined to the binary dichotomy of wrong/correct. For instance, the seriousness of confusion caused when substituting partial synonyms as in the big/large class is not the same as that caused by synonyms which are not mutually interchangeable in a certain context as in big girl/large girl. However, one way to avoid the drawbacks of quantification is to grade errors by seriousness: major, minor, weak point, etc. The problem then is to seek an agreement amongst translation instructors on what constitutes a major, as opposed to a minor, error. For example, an error in translating numerals may be considered very serious by some, particularly in financial, scientific or technical material, yet others will claim that the client or end user will recognize the slip-up and automatically correct it in the process of reading (Williams 2009).

2.4 The Interpretation Criterion

The interpretation criterion takes the ST as a point of departure. It is precisely about how far the students' interpretation of the ST personified in the TL is correct or deviant. The instructor checks on the basis of a comparison between ST and TT to see whether all the information is included, and nothing is added, omitted and/or different (Larson 1984). In other words, the criterion relates to the traditional paradigm of faithfulness in translation. Failure to be faithful to the ST can be either conscious or unconscious and the distinction between the two is essential in translation quality assessment.

If the students consciously deviates from the ST in order to fulfil demands of the readership, the assessment procedure should be rather appreciative unless the circumstances are inappropriate. In the absence of such information, the translator is required to decipher and interpret the ST in a way that makes its meaning less ambiguous for the TL reader. However, there are indeed cases where the translator must not shift from the ST using his/her own interpretation. For example, as Hatim and Mason (1990: 7) illustrate, "at crucial points in diplomatic negotiations, interpreters may need to translate exactly what is said rather than assume responsibility for re-interpreting the sense". On the other hand, if the translator unconsciously shifts from the ST, the effect on the quality of translation is likely to be serious and the error is, therefore, to be assessed as such. Such errors are most often a result of misinterpretation of the ST which in turn produces a betrayed version of the ST. This criterion is, therefore, ST-centred in the sense that it maintains that "first loyalty is at all times with the source text" (ibid.: 17). Accordingly, the quality of translation lies in the ability to comprehend and interpret the ST correctly.

2.5 The Naturalness Criterion

It is the extent to which translation should be integrated and read as a natural TL text. The translator may understand correctly the ST and even convey easily a discernible message to the TL reader. However, the TT may not reflect the natural and idiomatic forms of the receptor language (Larson 1984). This means that the TT does not read naturally for the TL reader as the ST does for the ST reader. A naturalistic approach seeks a domestication of the ST into the TL and culture, thus compromising the culture-specific meaning of the ST. This process of acculturation often denies the TL readers the opportunity to acquaint themselves with foreign thought patterns and violates the fundamental principle of historical fidelity in translation (Beekman and Callow, 1974). On the other hand, encouraging a non-naturalistic approach to translation has the benefit of enriching the linguistic repertoire of the TL, i.e. the incorporation of SL features into TL features helps TL readers develop their potential for new terminology. This process is referred to by Neubert (1990) as translational cross-fertilisation.

In order to achieve naturalness, the translator sometimes has to take a necessary risk to produce an equivalent effect to that of the original text. This view has been reflected in the instructors' assessment of the students' errors as attempts to acculturate the ST into the TL were rarely pointed out by instructors. It should be noted here that the naturalness of a text could be checked by native speakers of the TL. Errors relating to naturalness are often a result of cross-linguistic differences at the discourse or stylistic level, such as that in the arrangement of information between Arabic and English. This can be clearly seen in rhetoric and stylistic differences between the two languages. For instance, more peculiar to Arabic than to English is the tendency to combine repetition and parallelism to create a stronger effect. For instance, the Arabic equational sentence al-kifaH wa al-jiha:d wa al-nithal dhida al-istiCma:r (literally: the struggle and the fight and the jihad [wholly war] against the occupier) could be translated into English as: The struggle against the occupier. It is important to note that the positive response which the repetition of form and meaning maygenerate at the SL level is unlikely to be preserved if it is kept as such in English. Cutting down the repetition load in the Arabic ST when translating into English will produce a more natural translation as far as the TL is concerned. From the discussion above, we claim that no single criterion can deal with all aspects of translation quality assessment. Therefore, I shall investigate instructors' awareness and rating of these criteria in their assessment of the students' errors.

3. The Questionnaire and Assessment Criteria

The main purpose of this questionnaire is to investigate to what extent instructors make use of the evaluation criteria mentioned earlier and how consistent and reliable their assessment is. The analysis is twofold: the first is concerned with instructors' interaction with the five previous criteria of assessment and the second with their intra-and inter-consistency. Consistency can be defined in the context of this work as giving consistent information about the value of a learning variable being measured. As to inter-consistency, it is related to the production of similar judgments by different instructors when evaluating the same sample; the more similar the scores are, the higher is the inter-consistency achieved and vice versa. On the other hand, intra-consistency is achieved when almost identical test-results or scores are obtained each time the same sample or an alternative form is administered to the same group or individual.

The questionnaire consists of twenty translation errors taken from the analysis of students' translations of four texts, one from Arabic into English and three from English into Arabic. Copies of the source texts are attached to the questionnaire. The choice of errors was random but representative at the same time. That is to say, there was a selection of all possible categories of errors that can generate different criteria of assessment, four error-samples for each criterion, but the choice between errors of the same type was random (see tables below). The instructor scores the translation test on the basis of how well the candidate has comprehended and maintained the meaning of the original message and how well he/she has dealt with the mechanics of the target language, such as grammar, vocabulary and spelling.

As to the error severity, the majority of models of evaluations contain three severity levels which can be summarized as minor, major, and critical. There is general agreement across the models regarding the meaning for the three main categories: minor errors are those that are noticeable but which do not have a negative impact on meaning and will not confuse or mislead the user. Major errors are considered to have a negative impact on meaning, while critical errors are considered to have major effects not only on meaning, but on structure as well. Other models of rating and classifying students' errors have five levels, but these are not specifically severity levels, but rather star ratings, with 1 being the worst and 5 being the highest (O'Brien, 2012). I have slightly amended the rating of this model to suit the purpose of the questionnaire in question as 0 for no error, 1 for minor, 2 for major, 3 critical, 4 for serious and 5 very serious error.

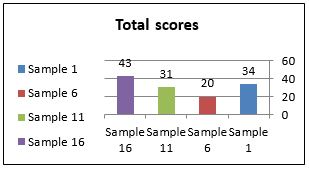

Before proceeding with the analysis of consistency, it is worth mentioning that the primary aim of this analysis is not only to pinpoint those elements where instructors fail to be consistent but also to highlight areas where they show shared criteria of evaluation. I reordered the samples according to the criteria they mostly violated and the ones they were intended to test. In other words, one sample may involve the violation of more than one criterion but in most cases, it is set to test one of this criterion. For instance, under the category of frequency, samples 1, 6, 11 and 16 were administered with the purpose of examining the instructors' use of the frequency criterion. Therefore, the instructors' inter-consistency of each criterion will be examined separately.

3.1 Rating the Frequency Criterion

This means that samples with a high frequency of errors will receive high scores. In fact, the questionnaire deliberately involves samples with a considerably high number of different types of error. Some of these samples deviate from the meaning intended in the ST while others, though erroneous, still transfer the meaning existing in the ST. Samples 6 and 11 in table one, for example, illustrate the types of erroneous construction which do not affect the ST's intended meaning. The two samples involve all types of errors, yet evaluators’ ratings remain average. (see all samples in appendix one).

|

Evaluators |

Sample 1 |

Sample 6 |

Sample 11 |

Sample 16 |

|

I |

3 |

3 |

2 |

4 |

|

II |

5 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

|

III |

3 |

1 |

4 |

5 |

|

IV |

4 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

|

V |

3 |

1 |

3 |

3 |

|

VI |

2 |

0 |

1 |

5 |

|

VII |

3 |

0 |

3 |

5 |

|

VIII |

3 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

|

IX |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

|

X |

4 |

1 |

3 |

5 |

|

Total scores |

34 |

20 |

31 |

43 |

(Table One: ratings of frequency errors)

Total scores of frequency samples

As can be seen from Table One, instructors' ratings of sample 6 are relatively small. Apart from evaluators II, IV and IX almost all scores are equal or below 3. Both samples, 6 and 11, involve frequent errors, yet sample 11 is penalised more heavily than sample 6. This implies that instructors are either inconsistent or the errors involved in the two samples are not the same. The first possibility is very unlikely, given that the four lowest scores were rated by those who did not identify the errors. This confirms the idea that identification of translation errors is not always an easy task.

Most errors in sample 6 are not as explicit as in sample 11 because they are semantic errors in partial synonymy with the more appropriate renderings (see appendix One). This makes them less obvious than say syntactic errors. Such partial semantic or pragmatic losses usually pass unnoticed as the sentence (text) is grammatically well formed and the core meaning is still in effect. However, the same cannot be said about the agreement and case-marking errors in sample 11. These errors are a blatant breach of grammatical rules in the sense that they cannot be exchangeable with the correct grammatical forms and are therefore more marked in terms of their identification. Unlike errors in sample 6, errors in sample 11 have been identified by most instructors and therefore are more prone to receive higher scores. In fact, evaluators VI and VII marked sample 6 as 0, i.e. error-free. To find out whether this group of evaluators would have rated the errors highly, had they discovered them, will depend on how they score other samples with frequent errors.

So far, the first score results indicate that evaluators III, V, VI, VII and X failed to recognise the majority of errors, if any at all because they did not associate seriousness of error with frequency. The second score results show that evaluators I, II, IV and IX penalised constructions with high rate of errors. The question that arises here is whether they uphold the same judgement when the frequency of errors affects the quality of the text or involves errors which alter its meaning. Samples 1 and 16 are best suited to testing instructors' reactions to this type of frequency.

The results drawn from these four samples indicate that instructors exercised their evaluation differently. For instance, evaluators II, IV and IX associated seriousness with frequency as their scores were high regardless of whether the high frequency of errors involved incomprehensibility or semantic alteration of the message. On the other hand, evaluators VIII and X demonstrated a kind of leniency towards frequency which did not affect the quality of the message but showed less tolerance when the semantic content of the SL message was altered. Most evaluators, however, assessed samples with a high distribution of quality errors (e.g. samples 1 and 16) as very serious. One may wonder whether instructors' reaction was due merely to the quality of the error or to the interaction of the two principles of quality and frequency. This can only be determined by considering erroneous constructions that involve a low frequency with a high threat to the quality of the message.

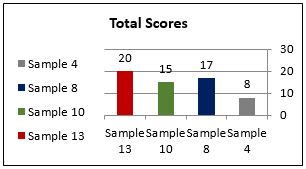

3.2 Rating the Generality Criterion

The generality criterion presupposes that infringement of general rules triggers the instructors' reaction and, therefore, high-rating scores. The questionnaire involves several samples with errors that violate general rules, some of which can change the intended message. However, there is also the possibility that this reaction was triggered merely by the fact that the error committed is of a syntactic type. To confirm either explanation, we should resort to other samples involving mere grammatical errors without a significant effect on the content of the ST. We shall consider in this respect the instructors' assessment of samples 4, 8 and 10 in Table Two. Samples 8 and 10 involve an agreement error and a shift in tense respectively while translating into Arabic. Sample 4, on the other hand, has been made when translating into English and involves a prepositional error.

|

Evaluators |

Sample 4 |

Sample 8 |

Sample 10 |

Sample 13 |

|

I |

0 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

|

II |

1 |

4 |

3 |

3 |

|

III |

0 |

1 |

1 |

5 |

|

IV |

1 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

|

V |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

|

VI |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

|

VII |

3 |

2 |

3 |

3 |

|

VIII |

1 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

|

IX |

1 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

|

X |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

Total Scores |

8 |

17 |

15 |

20 |

(Table Two: ratings of generality errors)

Total scores of generality samples

The examination of instructors' use of the generality criterion and, more particularly, their reaction towards grammatical errors shows interesting but natural results. Throughout their evaluation of the questionnaire, they usually mark samples involving a violation of the generality principle very leniently. We have also observed that grammatical errors are more readily detected when English is the TL as well as when they affect the content or the communicative goal of the text. However, regardless of the direction (i.e. from English into Arabic or vice versa) mere grammatical errors are often scored alike. That is, grammatical errors either in English or in Arabic are assessed tolerantly if they do not represent a threat to the accuracy or intelligibility of the message. This is clearly demonstrated by sample 4 as most instructors detected the grammatical errors it involves, yet it received the lowest score given that the message is still in effect. This reinforces our claim that non-native instructors of a language are more alert, in the sense of possessing facility in detection, to grammatical errors than their native peers.

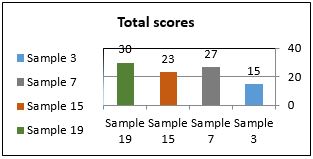

3.3 Rating the Intelligibility Criterion

Violation of the intelligibility criterion means that the message conveyed in the TT is either distorted, incomplete or simply incomprehensible.

|

Evaluators |

Sample 3 |

Sample 7 |

Sample 15 |

Sample 19 |

|

I |

1 |

3 |

4 |

3 |

|

II |

2 |

2 |

5 |

5 |

|

III |

1 |

3 |

5 |

4 |

|

IV |

2 |

5 |

0 |

3 |

|

V |

2 |

2 |

2 |

4 |

|

VI |

0 |

1 |

4 |

1 |

|

VII |

1 |

3 |

0 |

3 |

|

VIII |

1 |

1 |

0 |

3 |

|

IX |

3 |

4 |

3 |

0 |

|

X |

2 |

3 |

0 |

4 |

|

Total scores |

15 |

27 |

23 |

30 |

Table Three: ratings of intelligibility errors)

Total scores of intelligibility samples

As can be seen from Table Three, the intelligibility principle is sanctioned less tolerantly than the generality one. The average total score of an intelligibility sample is almost 23, whereas that of generality is only 15 although this is not as high as that of frequency. This could refute the preceding claim that evaluators have assessed the errors in terms of their quality and not of their frequency given that violation of the intelligibility criterion involves quality errors. The rating of sample 15 is similar to that of 7 as they both involve a wider dispersion of marks than that existing in samples 3 and 19. That is, while most marks are equal or below 2 in sample 3 and equal or over 3 in sample 19, samples 7 and 15 involve all types of scores from 0 to 5.

In sample 15, half of the evaluators, I, II, III, VI and IX, have identified the error. Although failure to identify this error may hinder generalisations about instructors' assessment, this demonstrates that this type of error is more prone to pass unnoticed by instructors and can therefore become a consistent habit of students as long as it is undetected. Errors of partial synonymy, though often they do not affect the general meaning of the text as in sample 15, can be very serious especially when they involve an ideological shift between two languages with two conflicting and competitive ideologies.

3.4 Rating the Interpretation Criterion

In this criterion, the focus is on samples 12 and 14 rather than samples 5 and 9 as they are unrepresentative. Not all errors are due to grammatical or semantic incompetence in the TL; they can also follow from a misinterpretation of the ST itself. As a result, sample 12 received a high score because its individual scores are equal or over 3 (most of them are fours and fives).

|

Instructors |

Sample 5 |

Sample 9 |

Sample 12 |

Sample 14 |

|

I |

2 |

1 |

4 |

2 |

|

II |

2 |

2 |

5 |

4 |

|

III |

1 |

2 |

4 |

3 |

|

IV |

0 |

0 |

5 |

5 |

|

V |

0 |

0 |

3 |

3 |

|

VI |

0 |

0 |

3 |

3 |

|

VII |

1 |

1 |

5 |

3 |

|

VIII |

2 |

0 |

3 |

2 |

|

IX |

3 |

3 |

4 |

3 |

|

X |

1 |

0 |

3 |

4 |

|

Total Score |

12 |

9 |

39 |

32 |

(Table Four: ratings of interpretation errors)

Total scores of interpretation samples

A closer examination shows indeed that the two samples differ in terms of the quality and quantity of errors they involve. The error frequency in sample 12 is higher as it involves infringements of grammatical rules such as the subject-verb agreement and errors due to the misinterpretation of the ST. However, in both cases, the errors are not as marked as in sample 12. As for the potential confusion at the TT level, it is unlikely to be recognized especially when the text is read as a whole. This difference in terms of the frequency and generality principles cannot explain the high score given to sample 12 because instructors’ evaluation of previous samples has shown that frequency and generality were often assessed with leniency.

The major difference between samples 12 and 14 lies in their effect on the quality of the message in the TL. The translation in sample 12 is an altered form of the ST. On the other hand, no alteration is clearly identifiable in sample 12 and the misinterpretation of the TT is only potential and cannot be realized without feedback from the ST. It follows that less discrete errors are likely to be assessed more seriously. In other words, the alteration in sample 12 is more marked given that it is manifested in the text and easily retrievable without even having recourse to the ST. However, the discreteness of sample 14 resulted from the fact that the errors are a potentiality but not actual errors that are readily recognizable without the reading of the ST.

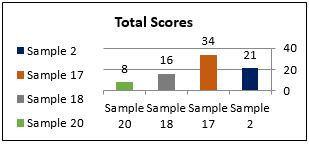

3.5 Rating the Naturalness Criterion

The content and form of a text can be translated satisfactorily, yet the translation may feel unnatural for the TL reader. The four samples represent, in this respect, some failures to observe the naturalness principle.

|

Instructors |

Sample 2 |

Sample 17 |

Sample 18 |

Sample 20 |

|

I |

2 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

|

II |

1 |

3 |

1 |

3 |

|

III |

1 |

5 |

2 |

0 |

|

IV |

5 |

4 |

1 |

0 |

|

V |

2 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

|

VI |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

VII |

1 |

5 |

3 |

1 |

|

VIII |

3 |

3 |

2 |

0 |

|

IX |

4 |

4 |

2 |

0 |

|

X |

2 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

|

Total Scores |

21 |

34 |

16 |

8 |

(Table Five: ratings of naturalness errors)

Total scores of naturalness samples

Again, evaluators' assessment varies from one sample to another, for instance, almost all scores of sample 17 are equal to or over 3 with a high total score of 34 whereas the other samples' scores are relatively small. This can be attributed to the fact that the Arabic translation consists of many inaccuracies: first, it reads unnaturally owing to the inappropriate use of repetition. Repetition is a common feature of Arabic; its use is not random but always has a function or purpose such as cohesion or emphasis. This reason alone does not explain the high score given to sample 17 because other samples involving stylistic awkwardness were assessed tolerantly. It is also noticed that the total scores of samples 18 and 20 are lower than that of sample 2. This is because sample 2 is a translation into the foreign language (English) and evaluators are expected to be less tolerant when evaluating the students' performance in the TL. Most instructors did not recognise the errors in sample 20. This low score is likely due to the discreteness of the errors. However, the high score, 34, given to sample 17 cannot be explained in terms of the generality or intelligibility criterion as the translation is grammatically well formed and semantically comprehensible. We have seen that the distortion of the ST's message was often regarded as serious especially when it was readily identified.

4. Concluding Remarks

From the discussion of instructors' evaluation in the previous section, it can be claimed that there is an imbalance in their assessment in terms of the different criteria and tools available for this purpose. Such an imbalance can have undesirable effects on the teaching/learning process. The inconsistency in instructors' evaluation is likely to cause confusion for the trainees and mask the clarity of the course objectives. As mentioned before, consistency will be looked at from two related angles: inter-consistency and intra-consistency.

|

Criterion |

Level of inter-consistency |

Level of Intra-consistency |

|

Frequency |

Acceptable |

Low |

|

Generality |

Minimal |

Low |

|

Intelligibility |

Relative |

Relative |

|

Interpretation |

High |

Low |

|

Naturalness |

Low |

relative |

Table Six: Rating the level of inter-and intra-consistency among the instructors

The results, summarized in table six, show that the level of inter-consistency amongst the instructors is relatively satisfactory because most of them severely penalised errors which affect the core meaning of the ST. As two intra-consistency, the level was low because the instructors lack agreed upon assessment criteria. This could be attributed to the fact that English and Arabic are incongruent and to the interdisciplinary nature of translation which makes it difficult to be treated in a systematic way. The alarming observation, which can be inferred from their evaluation, is that the analysis and assessment of the students' translations are often performed at the surface level. Instructors, in the process of their assessment, checked upon the main content of the ST without paying equal attention to the cultural and pragmatic aspects of translation such as ideological shifts, inter-textual meanings, naturalness and collocative patterning of words.

The discussion of evaluators’ assessment in terms of the evaluation criteria gives us a general account of their approach to the gravity of errors in translation. The seriousness of an error is often associated with two main values: (i) distortion of a ST's meaning or incomprehensibility of the message enacted in the TT and (ii) markedness/unmarkedness of the error. Value (i) represents errors which distort the meaning existing in the ST or simply make it unintelligible regardless of the criterion that has been violated. Value (ii) assesses the degree and explicitness of the loss of meaning in translation. Discrete errors like partial synonymy or ideological shifts are often assigned low scores when they are identified. These two values can also trigger a higher penalisation when combined with frequency. This is because translation which involves, in addition to the alteration or incomprehensibility of the message, a high frequency of errors is likely to be assigned a higher gravity score.

From what preceded, it transpires that evaluation is an important element of translation teaching for it is a feedback from which instructors check upon their students' achievements and needs. To be so, it must probe into all meaning aspects that are crucial to a successful translation. In the case of our evaluators, apart from the semantic content, almost all other aspects were overlooked. Instructors' feedback from their evaluation in this context is not of much help, as it does not cover all students' needs. It can even be misleading if instructors design their own syllabus, remedial teaching or completion of the course based on the findings of this kind of evaluation. Indeed, frequent recurrence of an error-type among students should urge instructors to view their teaching methods and material, and consider re-teaching or remedial measures if necessary. This is because high frequency of an error-type means that the teaching method either ignores aspects that represent the students' areas of difficulty or fails to address them correctly.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Almijrab, R. (2013). Evaluation of Translation Errors: Procedures and Criteria. DOI:

10.7763/IPDR. V62. 13- 58-65.

Beekman, J. and Callow, J. (1974) Translating the Word of God. Grand Rapids: Zondervan

Publishing House.

Davies, E. (1982). Some Possible Criteria for the Evaluation of Learner's Errors. Paper presented in

Mate C\ Conference, Fez.

Goff-Cfouri, C. (2014) Testing and Evaluation in the Translation Classroom.

translationjournal.net/journal /29edu.htm

Hatim, B. and Mason, I. (1990) Discourse and the Translator. London: Longman.

Hatim, B. and Mason, I. (1997) The Translator as Communicator. London: Routledge.

House, J. (1977) Translation Quality Assessment. Tübingen: Gunter Narr Verlag.

Kiraly, D. (2000) Social Constructivist Approach to Translator Education. Manchester: St. Jerome,

Kupsch-Losereit, S. (1985). The Problem of Translation Error Evaluation. In Titford, C. and Hieke,

A. (eds.), Translation in Foreign Language Teaching and Testing. pp. 169-79 Tübingen: Gunter Narr.

Kussmaul, P. (1995). Training the Translator. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Larson, M. (1984) Meaning-based Translation: A Guide to Cross-Language Equivalence. Lanham:

University Press of America.

Malone, J. (1988) The Science of Linguistics in the Art of Translation. Some Tools from Linguistics

for the Analysis and Practice of Translation. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Neubert, A. (1990) The Impact of Translation on Target Language Discourse: Text vs. System. Meta

35:1, 96-101.

Norish, J. (1983) Language Learners and their Errors. London: Macmillan.

O'Brien, S. (2012) Towards a Dynamic Quality Evaluation Model for Translation. The Journal of

Specialized Translation No.17

Pym, A. (1992) Translation Error Analysis and the Interface with Language Teaching. In Cay

Dollerup, C. and Loddegaard, A. (eds.) The Teaching of Translation. Amsterdam: Benjamins, pp.279-288.

Williams, M. (2009) Translation Quality Assessment. Mutatis Mutandis. Vol. 2 No 1. 2009. pp. 3-23.

Appendix One

The Questionnaire

Dear participant

This questionnaire follows an elaborate examination of trainees' errors in translation. Its purpose is to incorporate the evaluator’s view of error evaluation into our own analysis.

The following samples are taken from the translations of four texts translated by semester eight undergraduate students at Benghazi University, Benghazi, Libya. The samples involve different types of errors which you are kindly requested to evaluate. You will find enclosed the four source texts.

A. Extracts of Arabic-English Translation: Text One (Argumentative)

Sample 1, Text One, lines 30-31

ويعبر الموقف المصري عن اجماع عربي واسلامي لم يعد يتحمل الصمت الغربي عن السلاح النووي الاسرائيلي

The Egyptian attitude expressed to the Arabic and Islamic community, which will not tolerate any more for the Western silence on the Israeli nuclear weapon.

Sample 2, Text One, line 28

ترفض إسرائيل بحث سلاحها الكيميائي أو موضوع السلاح الكيميائي في الشرق الاوسط

Israel refuses the search for its chemical weapons or the subject of chemical weapons in the Middle East.

Sample 3, Text One, line 23

استمرار الرفض الليبي تسليم متهميه في حادث تفجير طائرة بان ام فوق اسكتلندا.

Libya still refuses to extradite its two suspects in the accident of Pan Am explosion over Scotland.

Sample 4, Text One, lines 2-3

فالولايات المتحدة تبنت دورا رياديا لمصر منذ اتفاقية السلام الإسرائيلية المصرية

The United States adopted a leading role to Egypt since the Egyptian-Israeli peace treaty.

Sample 5, Text One, lines 15-16

عزز انفتاح مصر الدور الريادي التي كانت لعبته مرات عديدة في التاريخ العربي المعاصر والحديث.

Egypt's leading role which she played many times in both ancient and contemporary Arab history has consolidated its open-door policy.

B. Samples of English-Arabic Translation: Text 2 (Argumentative), Text 3 (Expository), and Text 4 (Instructive).

Sample 6, Text 3, lines 1-3

Man seized what lay around him to fashion it into tools with which to hack, carve, pound and sew his way through life.

واستفاد من كل ما حوله وصورها على هيأة أدوات بواسطتها يستطيع العزق والنحت والسحق و يشق طريقه في الحياة

Sample 7, Text 4, line 1

How to treat your wart, verruca, com or callus. كيفية معالجة ثآليل القدم وغيرها.

Sample 8, Text 2, lines 21-22

... what raised eyebrows was not the loss of the satellites but Russia's inability to replace them.

وما اثار الدهشة ليس فقط فقدان الأقمار الصناعية بل عجز روسيا على استبدالها.

Sample 9, Text 4, lines 40-42

If the affected area is on the sole of the foot, cover it with an adhesive plaster.

...اذا كانت المنطقة المصابة في اسفل القدم فضع عليها شريطا لاصقا.

Sample 10, Text 3, line 6

... before that trial and error will suffice. وقبل ذلك فان المحاولة والخطأ ستفي بالغرض.

Sample 11, Text 4, lines 10-12

Treatment can take up to twelve weeks for resistant lesions.

من الممكن أن تتطلب المعالجة اثنى عشرة أسبوع للأضرار المقاومة.

Sample 12, Text 2, lines 2-3

Ever since the fall of communism, the agency that gave the world Sputnik, Gagarin and the space station Mir appeared to have fallen too, ...

فمنذ انهيار الشيوعية، تلك الهيأة التي قدمت للعالم القمر الصناعي اسبوتنيك ، قد جر خلفه انهيار جاجارين والمحطة الفضائية مير.

Sample 13, Text 4, line 39

Replace the cap tightly. أعد وأغلق غطاء القارورة بأحكام.

Sample 14, Text 3, lines 14-15

... the researchers presenting it can use that knowledge to build new properties into matter.

والباحثون الذين يمثلونه يستطيعون استعمال ذلك العلم في تشكيل خواص جديدة للمادة.

Sample 15, Text 2, lines 22-23

In the wake of the Mars debacle, .في أعقاب فشل رحلة الفضاء الى المريخ.

Sample 16, Text 2, lines 1-2

F or the Russian space programme, the comeback was supposed to begin last month.

كان من المتوقع فأن برنامج الفضاء الروسي بدأ في العودة الى الوراء من الشهر الماضي.

Sample 17, Text 3, lines 4-6

It is only when you make materials from scratch that knowing why things as they are begins to matter.

اننا عندما نقوم بصنع شيء من لأشي فإننا نعلم لماذا صنع هذا الشيء أما قبل ذلك فلا نعلم شيئا عن المادة الخام.

Sample 18, Text 4, line 8

Every night, soak the affected area(s) in warm water. أغمر كل ليلة المنطقة المصابة في مياه دافئة.

Sample 19, Text 3, lines 8-11

They have developed a wide field of material science that seeks to explain what arrangements of matter at a microscopic level give rise to the properties of substances.

قاموا بتطير ميدان واسع في علم المادة يسعى الى تفسير ما سببته أنظمة المادة تحت المجهر في خواصه.

Sample 20, Text 2, line 11, 12, 13

But last month, the grand promenade to Mars turned into a near earth lob shot, when a booster malfunction sent the spacecraft plummeting back to earth shortly after its launch.

لكن في الشهر الماضي فان الاحتفال الكبير بإطلاق سفينة الفضاء الى كوكب المريخ تحول الى ضربة مستديرة بالقرب من الأرض وذلك بسبب خلل في صاروخ الدفع الذي تسبب في سقوط سفينة الفضاء على الأرض بعد اطلاقها بقليل.