January 2018 Issue

Read, Comment and Enjoy!

Join Translation Journal

Click on the Subscribe button below to receive regular updates.

“The trick was to find adequate words”: An Investigation into the Effect of Mood on Translation Products

- Details

- Written by Tanya J. Bain and Séverine Hubscher-Davidson

Abstract

Psychological studies suggest that positive and negative affective states have clear differential impacts on daily tasks such as cognitive processing, problem solving and decision-making. Despite its potential relevance for translation performance, the role of mood on translator behaviour has not yet been fully explored. This article aims to shed light on the impact of translators’ moods on their final translation products by reporting on a case study. Six student translators were asked to complete a short translation from French into English following a mood induction procedure. Results from the study indicate that less extreme moods may be conducive to a more successful translation performance, and that contrasting mood states foster the use of different translation processing styles. Implications for translator training are discussed.

Keywords

positive mood; negative mood; cognitive processing; problem solving; decision-making; translator training.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the study participants who willingly volunteered their time and effort to partake in this research.

Introduction

A search carried out on April 6th 2016 for the keyword “mood” in the title category of BITRA, the Bibliography of Interpreting and Translation hosted by the University of Alicante’s Department of Translation and Interpreting, did not return any results relating to the impact of mood on translation performance.[1] The role of affect in translation performance, however, has received increasing attention in the Translation Studies literature. Process research studies have recently focused on the influence of affective factors on various aspects of translators’ and interpreters’ work, such as translation strategies, career success, and job satisfaction (e.g. Bontempo and Malcolm 2012; Rojo López 2014; Hubscher-Davidson 2016). Nevertheless, the specific role of mood on translation performance has received very little attention.

A growing body of empirical research in the field of psychology indicates that mood can affect performance on a number of different cognitive tasks, such as following task instructions and thinking about problems in new ways (Schwarz 2002; Gasper 2003; Martin and Kerns 2011). Translation processing involves “clusters of specialized cognitive abilities” (Muñoz Martín 2014:55) and, as such, it may likewise be influenced by translators’ moods. Consequently, translation products may bear traces of these affective states. Mood, which can be defined as a “momentary, subjectively experienced state of mind […] that can be described in terms of feeling good/feeling bad” (Schwarz 1987:2), has been shown to influence a wide range of aspects of clear relevance to translation: cognitive processing style, decision-making, creativity and problem-solving ability (Greene and Noice 1988; Isen 1984, 1987, 2008; Davis 2009). Positive moods, for instance, are associated with efficient decision-making and problem-solving (Isen 2008), while negative moods have been linked to increased attention to detail and motivation (Schwarz 2002). Due to the impact of mood on various aspects of cognition and human behaviour, it seems relevant to investigate whether experiments testing the impact of mood on decision-making can be replicated in the context of translation performance.

The aim of this article is to explore the effect of translators’ positive and negative mood states on their translation products. The research questions to be addressed are the following: do final translation products reflect translators’ moods during the translation process? Does a positive/negative mood influence problem-solving differentially when translating? Ultimately, does mood affect translation? To address these questions, we will start with an overview of research in Translation Studies on this topic. Then, the concept of mood as it is understood in psychology and its impact on cognitive processing are discussed. Finally, the data gathered from a case study is analysed, and the article concludes with some recommendations for training and further research.

Translation Studies and Mood

As noted elsewhere (Hubscher-Davidson 2016), interdisciplinary work between Social Psychology and Translation Studies is still in its infancy. Pioneering work by scholars in Translation Process Research (TPR), such as Laukkanen (1996), Jääskeläinen (1999), Fraser (2000) and others, served to raise awareness of the differential impact of soft skills, such as confidence, during the translation process. More recently, individual differences such as empathy (Apfelthaler 2014), self-efficacy (Bolaños Medina 2014), and intuition (Hubscher-Davidon 2013) have received increasing attention in the TPR literature. These studies led to a greater understanding of the affective factors that influence translation processes, and the impact those factors can have on both process and product. They also contributed to furthering the links between TPR studies and neighbouring disciplines, thus strengthening a research field which is empirical-experimental in nature (Alves 2003). Although the concept of mood specifically has not been studied empirically in relation to translation performance, Lehr (2013) explored the role of emotions more generally in the translation process and found that positive and negative emotions[2] trigger different processing styles. For instance, her results indicate that positive emotions can improve creativity and style, while negative emotions can enhance accuracy in terms of terminology in translation. Building on her research, Rojo and Ramos Caro (2016) explored the impact that emotional reactions to negative and positive stimuli can have on translation performance in a specific experiment involving forty Spanish undergraduate translation students. Like Lehr, these scholars found that positive affect seemed to influence creativity, though their results were mixed when testing for accuracy. In the present study, it will be interesting to see whether the influence of mood will affect translation performance in a similar way to the specific and less diffuse affective states which were tested in these studies.

Only one piece of research has, to our knowledge, been carried out specifically on the relationship between mood and written translation. Davou (2007) investigated the effect of positive and negative source texts on translators’ moods, and observed that the first reading of a source text is paramount in enabling the translator to get a grasp of the emotional climate and essence of the text. She notes that source texts may have significant personal impact on translators, which could affect cognitive processing, and resulting translations. In this case, it can be argued that the initial emotional evaluation that translators make defines how they will subsequently cognitively process information. Davou (2007) observes that negative emotions may increase processing effort and decrease available cognitive resources while positive emotions may expand attention and creativity. This piece of research is invaluable as it is the first study of its kind and highlights the link between mood and cognition in the context of written translation. It does not, however, address the impact of translators’ moods on translation products empirically. In addition, Davou focused on the influence of a positive/negative text on translators’ moods, whereas the present study manipulates the translators’ moods prior to translating a neutral text.

Although drawn from interpreting rather than translation studies, there is another study worthy of mention which looked into the effects of a sign language interpreter’s mood on the two parties s/he was liaising between, i.e. a deaf client and their therapist. The study, led by Gold Brunson in 2009, was extended from a previous study in 2002 that demonstrated how an interpreter’s mood caused significant negative mood changes in the deaf participant, even when the therapist’s mood was neutral. The 2009 study also examined whether the mood and affective behaviour of the deaf client and of the therapist could impact on the mood (and thus the behaviour) of the interpreter. Traditionally, interpreters are trained to remain impartial and to “neither add nor subtract from the primary […] relationship” (Gold Brunson 2009:1), yet the study results indicated that the moods of both the therapist and the deaf client significantly impacted on the interpreter’s mood and could lead to damaged communication. This study initiated empirical evidence that sign language interpreters could be vulnerable to affective cues and susceptible to mood influences within a therapy setting.

Despite the fact that interpreters and translators work under different conditions, the results of the Gold Brunson study highlight that moods can have an influence on bilingual and cross-cultural communication practices. It therefore seems pertinent to investigate whether these findings also hold true for translators. In addition, recent work in the area of cognitive psychology on the links between mood and cognition calls for a more specific investigation into the roles that both affect and mood play in translation processing.

The Impact of Mood on Cognition

It seems important to distinguish and define the concepts of mood and emotions, as these are sometimes confused in the literature. While emotions typically involve a relationship with an object or event in the individuals’ environment that directs attention and encourages action (Zadra and Clore 2011), moods are more diffuse and less intense affective states that are not usually directed at particular objects or events (Davis, 2009). Moods are also believed to persist for longer periods of time than transient emotions (e.g. Berger and Motl 2000).

Research into mood indicates that mood states profoundly shape everyday aspects of life, from the course of judgement, to decision-making and problem solving (Martin and Clore 2001; Schwarz 2002; Gasper 2003). Empirical work on this topic has traditionally focused on two general mood states: positive and negative.[3] It can be argued that when an individual voices that they are ‘having a bad day’, this entails not only a bad mood but also overall negative performance across a multitude of daily tasks. Mood has been shown to have a differential effect on cognition and, more specifically, on cognitive control which is defined as “the mechanism that guides the entire cognitive system and orchestrates thinking and acting” (De Pisapia et al. 2008:26). As previously suggested, the interplay between mood and cognition may trigger different processing styles, thereby shaping the way in which individuals act, interact, and communicate (Beukeboom and Semin 2006).

Positive mood, for instance, has been shown to promote a broader focus of attention leading to more global processing of information (Isen 1987; Martin and Kerns 2011; Grol et al. 2014). A negative mood, on the other hand, is thought to lead to the adoption of more systematic and elaborate cognitive processing, traditionally paired with an increased focus on specifics (Clore et al. 1994; Schwarz 2000; Bless 2012). Putting aside for a moment the influence of other factors, one might speculate that a translator in a positive mood might process a translation task ‘globally’ by, for example, brushing over the specifics of a given source text. A translator in a negative mood, on the other hand, might process a translation task ‘systematically’ by spending a lot of time and effort pouring over every detail of the source text. The detail-oriented processing style associated with negative mood states could also mean a greater focus on terminological accuracy during a translation task, but perhaps also a more disjointed target text compared to that produced by a translator in a positive mood who would have a wider focus of attention. Indeed, research indicates that positive moods allow for a less effortful top-down processing style, focusing on general features of a situation, and contrasting with the detail-oriented, analytical and bottom-up processing style which a negative mood is said to induce (Schwarz 1990, 2002; Beukeboom and Semin 2006). Nevertheless, it has also been shown that when task demands (e.g. explicit instructions) require a detail-oriented processing style, individuals in a positive mood are also able and willing to engage in the effort.

It is noteworthy that mood has also been shown to influence judgement. In his ‘feeling-as-information’ theory, Schwarz (2012) conceptualizes the role of subjective experiences, including moods, in judgement. Assuming that people attend to their feelings as a source of information, with different feelings providing different types of information, Schwarz argues that more positive judgements are made when people are in a positive mood state. A study by Martin et al. (1993), which asked happy and sad participants to list birds, illustrates this point. When asked whether they were satisfied with what they accomplished, “happy” participants said they were satisfied and terminated the task, whereas “sad” participants were dissatisfied and continued to work on the task. This finding is consistent with the idea that positive moods result in less effort being exerted in task performance (e.g. Friedman et al. 2007).

Interestingly, this pattern was reversed when participants were asked whether they were enjoying the task. Those in a positive mood inferred enjoyment and continued with the task, while those in a negative mood demonstrated a clear lack of enjoyment and terminated the task. As Schwarz highlights, there are many variables that govern the use and impact of experiential information as a basis for judgement, and although “in both cases participants’ judgments were consistent with the valence information provided by their mood, this valence information had diverging behavioural implications, depending on the specific question on which it was brought to bear” (2012:297). With no questions asked to impact judgement-making, however, one of the implications of using mood as a basis for judgement in translation could be that translators in a positive mood would finish their translations sooner than translators in a negative mood, due to their potential tendency to be satisfied more quickly with their work and to expand less effort on it.

Problem-solving is also linked to an individual’s judgement. According to Schwarz (2002), a negative mood generally cues a “problematic” situation, whereas a positive mood will signal a “benign” situation where everything is perceived to be running smoothly. Individuals in a positive mood may therefore be more willing to take risks in exploring novel solutions, whereas individuals in a negative mood may tend to adhere consistently to established ‘safe’ strategies (Clore et al. 1994; Gasper and Clore 2002; Gasper 2003). According to Gasper (2003), positive moods therefore foster the ability to think about problems in new and flexible ways, which is necessary for problem solving tasks.

It follows, therefore, that creative-thinking tasks are believed to be mood-sensitive, with positive moods generally associated with innovation, original thinking, cognitive flexibility and divergent thinking (e.g. Davis 2009). This does not necessarily entail, however, that translators in good moods who are particularly creative will necessarily perform better in a translation task, as Bayer-Hohenwarter (2011) found a relatively low correlation between creativity and successful translation performance in her research. Nevertheless, we can speculate that translators in a positive mood are more likely to be flexible in their approach and to steer away from source text structures; on the other hand, translators in a negative mood might be more alert to translation problems and more focused in their efforts to resolve them.

In brief, we have seen that positive and negative moods may (1) trigger different processing styles, (2) lead to varying levels of expanded effort when making judgements, and (3) have a differential effect on problem-solving and creative thinking. In the case studies described in the following sections, we explore these assumptions and investigate how translators’ moods manifest themselves during the translation process, and what the consequences are for translation performance.

The present study

In addition to data collected from a mood measure, the study also collected data from background and retrospective questionnaires, as well as feedback and scores from anonymous markers on the participants’ translation work. The combination and triangulation of these various quantitative and qualitative methods aimed to increase precision in the description of the phenomena under investigation (e.g. Hansen 2008). In light of the preceding literature, the following two hypotheses were formulated:

Hypothesis 1. When working on a translation task, participants in positive mood states will have global processing styles, as evidenced by an increased focus on macrotextual features, and participants in negative mood states will have detail-oriented processing styles, as evidenced by an increased focus on microtextual features;

Hypothesis 2. When working on a translation task, participants in positive mood states will expand less effort and adopt more risky decision-making behaviours than participants in negative mood states who will dedicate more time and effort to solving translation problems.

Study

Participants

The sample used in this case-study comprised 6 students registered on a postgraduate translation programme in the UK, with 5 females and 1 male (mean age = 28.5 years). All participants worked with the language pair French-English. In terms of mother-tongue, 2 reported this to be English, 2 French, 1 Croatian and 1 German.

The setting allowed for a convenience sample and, as such, students taking part in the study were of different mother-tongues and women were over-represented. These circumstances impact on the representative nature of the sample and the results of this case-study cannot be generalized to the entire population of translators. Ideally, this study should be replicated in other settings and with other translators. Despite this limitation, it is of note that (1) all students had to have an excellent baseline knowledge of both languages to be allowed onto the course, and (2) there is likely to be comparability in terms of students’ mood-induced processing styles as all participants come from so-called Westernized and individualistic nations where it has been demonstrated that affective and cognitive behaviours are very similar (Gelfand et al. 2007).

Procedure

Participants were randomly assigned to either a positive or a negative mood group. Upon entering the research location (a university computer laboratory), participants were asked to sit at a computer of their choice. Three computers were set up with a positive mood induction procedure, and three with a negative mood induction procedure. Participants from both mood groups were presented with a consent form, a printed set of instructions (thus preventing any potential interruptions from the researcher), and a background questionnaire.

Both mood groups were then faced with a blank screen for 30 seconds to clear any moods or feelings present prior to the experiment. For the positive mood group, the aim was to induce the emotion of happiness. For this purpose, participants were shown a 2 minute clip from the Disney film The Jungle Book featuring the song “Bare Necessities”, which has been used in other studies to induce a happy mood (e.g. Beukeboom and Semin 2006). The negative mood group were shown an NSPCC advert from 2000, which provided alarming statistics and illustrated the negative effects of child abuse in the UK. This clip was used to induce a sad mood,[4] something which charity clips have been shown to induce (e.g. Robinson and Demaree 2007, 2009).

Participants were not informed of the underlying aim of the video clip at the start of the experiment, since existing literature suggests that mood induction is only successful if participants are not made aware that their mood is being manipulated (Bless et al. 1990). After watching the clip, participants completed a mood measure in order to ascertain the success of the mood manipulation. They were then asked to undertake the translation, and then to complete the retrospective questionnaire. Please refer to the appendices for copies of all documents relating to the experiment.

Participants completed the experiment simultaneously and in the same room. They were familiar with the study location, had access to any resources they deemed necessary, were not constrained by time, and could withdraw from the experiment at any point. They were offered a written explanation of the research aims at the end of the study, and the opportunity to obtain a copy of the final piece of research. All personal data collected were coded and anonymized, thus ensuring confidentiality.

At the end of the study, consent forms, translations and questionnaires were collected. A French native and an English native translation lecturer marked the anonymized translations. Neither was made aware of the study’s aims, or the context within which the participants had worked. They were asked to assess the work using a mark sheet especially designed for the study so that they could rate on a scale from 1 (very poor) to 5 (excellent) a number of aspects of the work (grammatical, lexical, idiomatic feel, etc.). Additionally, they were asked to provide some qualitative feedback, which will feed into the study discussion, and to give a score for each translation in line with the UK higher education percentage system, where a mark below 50% is a fail, 50-59% is a lower second-class mark, 60-69% is an upper second-class mark and 70% and above constitutes first-class work. All statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel.

Measures

Background questionnaire. Participants were first surveyed with a detailed background questionnaire in English enquiring as to education and years of translation experience. Participants also provided information on their working languages and potential areas of specialization. This enabled the gathering of detailed information on the sample participants.

Mood induction procedure. In order to induce either a positive or negative mood, participants were asked to watch one of two separate 2-minute video clips via YouTube prior to undertaking the translation task. Video-based mood induction procedures are among the most effective and widely used to induce moods in a group setting (Kucera and Haviger 2012). In order to check the effectiveness of the video clip, participants were asked to rate the clip on a positive/negative scale. The positive mood group gave their clip an average positive rating of 7/10, while the negative mood group gave their clip an average negative rating of 9/10. It can therefore be concluded that the video clips chosen were fit for purpose.

Mood measure. A mood measure was used to test the efficacy of the mood induction procedure. Participants were presented with a list of 6 adjectives (happy, sad, pleased, gloomy, miserable, satisfied) and asked to rate the extent to which these adjectives matched their current feelings on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much). These simple adjectives have been used frequently in previous mood research (Barrett 2004; Martin and Kerns 2011), as it is thought that employing more detailed emotional terms as manipulation checks invites casual attributions to determine the specific emotion, which can in turn eliminate the expected effect (Schwarz 2012).

Translation. Participants were asked to complete a 221 words translation from French into English. The source text, entitled “Guide de Paris Mystérieux” (Appendix 2) is a guide to Paris describing the lesser-known aspects of the city. This text was previously used in other TPR studies (e.g. Hubscher-Davidson 2009) and was deemed suitable for the present study due to its descriptive use of language and relatively neutral content. Participants were not given a brief in an effort not to encourage a particular type of processing style.[5]

Retrospective questionnaire. A retrospective questionnaire was given to the participants post-translation to gather information on their experience of the task and any difficulties encountered. Two questions in particular are of relevance to the present study and feed into the discussion of the study’s results: the first asked participants whether they thought that a translator’s mood affects the quality of their translation, and the second enquired as to whether they felt that their mood had affected their final translation product. With these questions, the intent was to give participants a voice in the research process and involve them in the study of themselves (Hubscher-Davidson 2011:8).

Analysis

Participants in the study are ranked from 1-6 in order of task completion: P1 was first to finish the translation and P6 was the last participant to finish the task. Target texts are referred to as TT1-TT6, and the two markers as M1 and M2.

Results

Mood measure

Results from the mood measure completed after the mood induction procedure can be seen in Tables 1 and 2. Similarly to other scholars (e.g. Martin and Kerns 2011), in order to assess how positive a participant felt after the video, their positive mood was calculated as the sum score of ratings of the positive mood adjectives (happy, pleased and satisfied). As can be seen in Table 1, participants 2, 3 and 4 (the positive mood group) gave their highest ratings to the positive adjectives, resulting in an average positive mood score of 10.3 out of 15 (each adjective having received a score out of 5). The same process was carried out to assess participants’ negative moods. Table 2 indicates that participants 1, 5 and 6 (the negative mood group) rated the negative adjectives most highly, resulting in an average negative mood score of 10 out of 15. These results indicate that the procedure was, on the whole, successful in inducing participants into the intended mood states. It is interesting to note, however, that P1 and P3 gave scores of 2 and 3 for each adjective on the mood measure. The mood induction seems to have affected these participants’ moods to a lesser extent than their peers, and they can be assumed to have started the translation with more neutral feelings than the other participants in the study.

Table 1. Mood Measure Results for the Positive Mood Group

|

+ or - |

Participant |

Happy |

Sad |

Pleased |

Gloomy |

Satisfied |

Miserable |

+ve feelings (sum) |

-ve feelings (sum) |

|

+ |

2 |

5 |

1 |

3 |

2 |

5 |

1 |

13 |

4 |

|

+ |

3 |

3 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

3 |

2 |

7 |

8 |

|

+ |

4 |

4 |

1 |

4 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

11 |

3 |

|

Average |

4 |

1.7 |

3 |

2 |

3.3 |

1.3 |

10.3 |

5 |

|

|

SD |

1 |

1.2 |

1 |

1 |

1.5 |

0.6 |

3.1 |

2.6 |

|

Table 2. Mood Measure Results for the Negative Mood Group

|

+ or - |

Participant |

Happy |

Sad |

Pleased |

Gloomy |

Satisfied |

Miserable |

+ve feelings (sum) |

-ve feelings (sum) |

||||||||

|

- |

1 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

9 |

9 |

||||||||

|

- |

5 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

4 |

1 |

3 |

3 |

10 |

||||||||

|

- |

6 |

1 |

5 |

1 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

4 |

11 |

||||||||

|

Average |

1.7 |

3.7 |

1.7 |

3.3 |

2.3 |

3 |

5.3 |

10 |

|||||||||

|

SD |

1.2 |

1.2 |

1.2 |

0.6 |

1.2 |

0 |

3.2 |

1 |

|||||||||

Translation assessments

Average scores for each criteria awarded by the markers to each mood group can be seen in Table 3. The negative mood group received their highest scores in the categories of ‘grammar’ and ‘terminology’. The positive mood group obtained their highest scores for ‘grammar’ and ‘stylistic features’. The negative mood group outperformed the positive mood group on the following features: ‘grammar’, ‘terminology’, ‘ST loyalty’ and ‘creativity’.

Table 3. Performance Scores for Each Mood Group

|

Averages |

|||||||

|

Stylistic Features |

Grammar |

Creativity |

Terminology |

Loyalty to ST |

Coherence |

Overall |

|

|

Positive mood group |

3.3 |

3.4 |

3.0 |

2.8 |

2.9 |

2.9 |

58.7 |

|

Negative mood group |

3.2 |

3.6 |

3.2 |

3.5 |

3.0 |

2.9 |

61.5 |

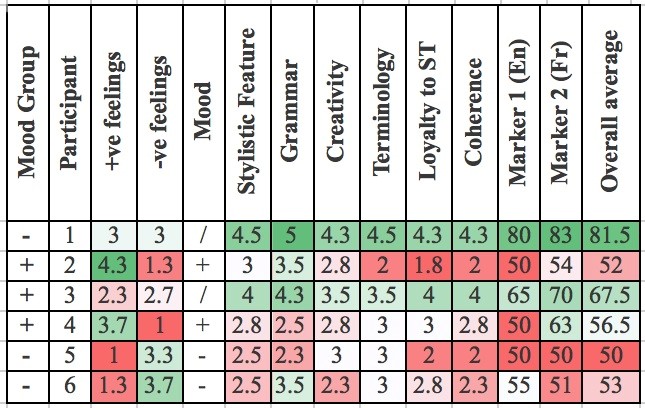

Figure 1 provides a heat map of the results of the study, with dark green representing a high score on one of the scales, and dark red representing a low score on one of the scales. Pale shades of each colour and white represent median scores. The heat map illustrates that P1 and P3, the participants whose moods were comparatively neutral, performed more successfully than their peers in the task, achieving green scores across all categories. P2, P5 and P6 performed less successfully than their peers. P5 in particular received red scores across the majority of categories.

Figure 1. A Heat Map of Moods and Average Scores

Discussion

In this study, a focus on macrotextual features (style, creativity, coherence) was assumed to be indicative of a global processing style pertaining to a positive mood state, while a focus on microtextual features such as grammar, terminology and ST loyalty was assumed to indicate a more systematic and detail-oriented processing style pertaining to a negative mood state. As expected, translators in the positive mood group scored highest overall on the macrotextual features, although the difference was marginal as they achieved an average score of 9.2 on these features as opposed to 9.1 for the microtextual features. This finding is in line with Lehr’s 2013 study which indicated that translators experiencing positive emotions performed better in terms of idiomaticity and stylistic adequacy. The results for the negative mood group were somewhat more striking, however, as they scored highest overall on the microtextual features, achieving an average score of 10.1 as opposed to 9.3 for the macrotextual features. Although this remains a relatively small difference, this group achieved their highest scores on the criteria of grammar and terminology, and outperformed the positive mood group on all microtextual features (terminology, grammar and ST loyalty). Altogether, these findings can therefore be said to lend some support to hypothesis 1.

The markers’ comments on the work produced by translators provided additional evidence of the differences in processing styles between the two groups. Their feedback on work produced by the positive mood group further reinforced the idea that their approach was less than systematic and detailed. M1, for example, commented that P3 showed some “lack of attention to detail” and that P2 was “frequently inaccurate”. P2 was the second translator to finish the task but obtained the lowest score, suggesting that they prematurely deemed their translation finished. It could be speculated that translators in positive moods in this study believed themselves to be in a “benign” situation (Schwarz 2002) and their work suffered as a consequence. Answers provided in the retrospective questionnaires also indicated that the positive mood group was more concerned with general and creative aspects of the tasks than with specific features: P2 mentioned the difficulty encountered with translating figurative language for maintaining overall sense, and P3 observed that translating the subtleties in literary texts is always a challenge. Some comments also suggested that these translators were not necessarily as absorbed by the translation task as they could have been. For instance, P2 mentioned not really engaging with the task and P3 commented that they felt distant from the text. The positive mood group therefore had a distinctly top-down and somewhat laissez-faire approach to the translation task.

In contrast, marker feedback on the negative mood group clearly highlighted a bottom-up approach. Work produced by translators in the negative mood group was described by M1 as focusing on words and syntax, with “little successful attempt to negotiate the cultural and rhythmic shifts” for P6, and “incoherence in English” for P5. These translators’ specific focus on terminology and their methodological, yet narrow, approach to the translation was also reflected in their retrospective questionnaires: P5 “doubted [themselves] and had to look everything up”, P6 summed up the task by stating that “the trick was to find adequate words”. This laborious approach and focus on specifics resulted in P5 and P6 being the last two participants to complete the task. It could therefore be argued that these translators believed themselves to be in a “problematic” situation (Schwarz 2002) and, as such, proceeded with more caution and made extra efforts compared to the positive mood group when making decisions and solving problems. In fact, answers provided in the retrospective questionnaires clearly indicated that the negative mood group was engaged with the translation task and focused on problem-solving and careful decision-making: P1 described the task as intriguing and intellectually challenging, and P4 discussed his problem solving strategies and “staying on the safe side” when making decisions. This is further evidence that the negative mood group had a bottom-up, effortful, and focused approach to the translation task. This finding is also concordant with the literature which suggests that individuals in sad moods tend to follow established “safe” strategies (Gasper 2003) and that negative emotions may increase processing effort (Davou 2007). These findings can therefore be said to lend some support to hypothesis 2.

The experiment also revealed some surprising findings. First, despite a particularly poor performance in terms of terminology, the positive mood group performed relatively well on the microtextual criterion of grammar. This finding could be explained by the experimental conditions themselves. As reported in other studies (Bless et al. 1996; Schwarz 2002), individuals in a positive mood are able to adapt to a more systematic, detail-oriented processing style should task demands require this. In this instance, it could be argued that translators in the positive mood group recognized the important role of grammar in this text for maintaining overall coherence, and consequently adapted their focus of attention.

Second, the results also indicated that the negative mood group outperformed the positive mood group on the macrotextual criterion of creativity. Although this may seem surprising in view of the literature suggesting a link between positive moods and creativity more specifically (Davou 2007; Lehr 2013), Martin et al. (1993) suggest that individuals in a negative mood are more likely to exert effort in a given task if they deem the task serious and important, while individuals in a positive mood are less likely to expand effort if they do not feel that the task is enjoyable. In this case, one of the translators in a positive mood (P2) commented retrospectively that their lack of interest in the text resulted in a struggle to “recreate the images of the ST in the TT”. This was confirmed by one of the markers who stated that “the choice of imagery is often clumsy” in TT2. P3 also mentioned a lack of enjoyment, noting that they were “unable to feel a connection with the text”. It could be argued that P2 and P3 did not enjoy the task and therefore made fewer efforts to render its creativity in translation than they may otherwise have done. These findings therefore lend additional support to hypothesis 2, though the exact nature of the relationship between positive moods and creativity is clearly a complex one.

Third, results also highlighted that P1 and P3 obtained the highest average scores on the translation task (81.5 and 67.5 respectively). As previously noted, their moods during the task can be considered relatively neutral. It is interesting to consider that translators in a neutral mood could be more effective in their problem-solving ability than translators in negative and positive mood states. In this case-study, it would seem that the two translators who did not let their mood influence their translation, or whose mood was not easily swayed, performed to a higher standard in the translation task. Indeed, the retrospective questionnaires revealed that neither P1 nor P3 had thought that their moods had affected their translation. In addition, M1 commented that these translations were both accurate and thoughtful/ intelligent, suggesting that P1 and P3 had managed to dedicate sufficient attention to both micro- and macrotextual features of the task. For P1, the background questionnaire also revealed extensive professional experience which may go some way towards explaining both the high quality of the translation and the relative emotional stability of the participant. Indeed, prior knowledge and past experiences have been shown to positively shape the functioning of emotional attention (Pourtois et al. 2013:507).

Limitations

Despite its interesting findings, this case-study is not without limitations. First, the sample of participants is not representative of the entire translation population. As such, the findings from the study may not have general applicability and further research is required to see whether findings could be transferable to other contexts. Second, the translation process can be affected by a number of different factors and, although care was taken in this study to control experimental conditions and to combine and triangulate methodologies and data, this does not mean that the study participants were not influenced by other factors alongside mood. For instance, experience and language competence can both affect the quality of target texts. The retrospective and background questionnaires provided useful complementary data, but all possible influencing factors could not be examined in the scope of this study. For instance, it would have been useful to compare the present results with participants’ scores in ‘normal’ circumstances, so as to understand whether and how performance differences reflect a genuine difference in translation or linguistic competence. Finally, although theories of affect can be used to shed light on aspects of translator behaviour and performance, it is important to recall that there are instances where the data did not perfectly corroborate or confirm the hypotheses. This reinforces the necessity to undertake further research into the potential influence of moods on translator behaviour before any claims can be made.

Conclusion

This study contributes to enriching our understanding of mood and its potential role in translation. Findings are generally consistent with previous research carried out by Lehr (2013) and Rojo and Ramos Caro (2016) in the sense that, like positive and negative emotions more generally, positive and negative moods triggered different processing styles in the present experiment. Although performance differences found between the groups were small, positive moods seemed to encourage a global and top-down approach, focusing on macrotextual features such as creativity and style, while negative moods appeared to foster a detailed and methodical bottom-up approach focusing on microtextual features such as terminological accuracy.

In light of these results, we would like to tentatively suggest that mood may play a role in shaping the kind of communication and social interaction that translation entails. Gold Brunson (2009:28) argued that the fact that interpreters are vulnerable to mood influences does not diminish the value of the interpreter profession, or suggest that interpreters are unprofessional. Likewise, we do not think that vulnerability to mood entails a lack of professionalism on the part of translators. However, translators need to understand that their work could be affected by their moods so that they are able to develop strategies for coping. For instance, it could be useful for them to be made aware of the possible risks associated with extreme moods and particular processing styles as part of their training and professional development. Focused training can develop translators’ awareness of the influence of affect on working behaviours, as “identifying, regulating, and using emotions is part of performing well as a translator” (Lehr 2014:5).

Educators may need to become more cognizant when it comes to translators’ emotional well-being and recognize the influence that affect could have on translation performance. Supportive learning environments are ideal contexts to explore these issues with budding translators, and to engage them in a discussion of relevant findings from related fields. Translator education programmes should encourage students to reflect on how they plan to manage their moods, stress, confidence and other interpersonal aspects. Formal learning about various psychological processes may help to mitigate their potential negative impact in practice.

The growth in research studies on affect in Translation Studies has not yet been matched by a parallel growth in teaching about affect in the translation classroom. Nevertheless, research studies such as this one may help us to identify ways in which we can effectively educate future translators about all aspects of their work.

References

Alves, Fabio (ed.) (2003) Triangulating Translation: Perspectives in Process Oriented Research, Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Apfelthaler, Matthias (2014) ‘Stepping into Others’ Shoes: A Cognitive Perspective on Target Audience Orientation in Written Translation’, MonTI, 1: 303-330.

Barrett, Lisa Feldman (2004) ‘Feelings or Words? Understanding the Content in Self-Report Ratings of Experienced Emotion’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(2): 266-281.

Bayer-Hohenwarter, Gerrit (2011) ‘Creative Shifts as a Means of Measuring and Promoting Translational Creativity’, Meta: Translators’ Journal, 56: 663-692.

Berger, Bonnie G. and Robert W. Motl (2000) ‘Exercise and Mood: A Selective Review and Synthesis of Research Employing the Profile of Mood States’, Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 12(1): 69-92.

Beukeboom, Camiel J. and Gun R. Semin (2006) ‘How Mood Turns on Language’, Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 42(5): 553-566.

Bless, Herbert, Gerd Bohner, Norbert Schwarz and Fritz Strack (1990) ‘Mood and Persuasion: A Cognitive Response Analysis’, Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 16: 331–345.

Bless, Herbert, Gerald L. Clore, Norbert Schwarz, Verena Golisano, Christina Rabe and Marcus Wölk (1996) ‘Mood and the Use of Scripts: Does Being in a Happy Mood Really Lead to Mindlessness?’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71: 665-679.

Bless, Herbert (2012) ‘Mood and the Use of General Knowledge Structures’, in Leonard L. Martin and Gerald L. Clore (eds)Theories of Mood and Cognition: A User's Guidebook, Hove/New York: Psychology Press, 9-26.

Bolaños Medina, Alicia (2014) ‘Self Efficacy in Translation’, Translation and Interpreting Studies, 9(2): 197–218.

Bontempo, Karen and Karen Malcolm (2012) ‘An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure: Educating interpreters about the risk of vicarious trauma in healthcare settings’, in Karen Malcolm and Laurie A. Swabey (eds) In Our Hands: Educating Healthcare Interpreters, Washington DC: Gallaudet University Press, 105-130.

Clore, Gerald, Norbert Schwarz and Michael Conway (1994) ‘Affective Causes and Consequences of Social Information Processing’, Handbook of Social Cognition, 1: 323-417.

Cohen, Joel B., Michel T. Pham and Eduardo B. Andrade (2008) ‘The Nature and Role of Affect in Consumer Behavior’, in Curtis P. Haugtvedt, Paul Herr and Frank Kardes (eds), Handbook of Consumer Psychology, New York: Erlbaum, 297-348.

Davis, Mark A. (2009) ‘Understanding the Relationship Between Mood and Creativity: A Meta-Analysis’, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 108: 25-38.

Davou, Bettina (2007) ‘Interaction of Emotion and Cognition in the Processing of Textual Material’, Meta: Translator’s Journal, 52 (1): 37–47.

De Pisapia Nicola, Grega Repovs and Todd S. Braver (2008) ‘Computational Models of Attention and Cognitive Control’, in Ron Sun (ed) The Cambridge Handbook of Computational Psychology, Cambridge/New York: Cambridge University Press, 422-450.

Fraser, Janet (2000) ‘What do Real Translators Do? Developing the Use of TAPs from Professional Translators’, in Sonja Tirkkonen-Condit and Riitta Jääskeläinen (eds), Tapping and Mapping the Processes of Translation and Interpreting: Outlooks on Empirical Research, Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 111-120.

Friedman, Ronald S., Jens Förster and Markus Denzler (2007) ‘Interactive Effects of Mood and Task Framing on Creative Generation’, Creative Research Journal, 19(2-3): 141-162.

Gasper, Karen and Gerd L. Clore (2002) ‘Attending to the Big Picture: Mood and Global vs. Local Processing of Visual Information’, Psychological Science, 13: 34-40.

Gasper, Karen (2003) ‘When Necessity is the Mother of Invention: Mood and Problem Solving’, Journal of Experimental Social Psyhology, 39: 248-262.

Gelfand, Michele J., Miriam Erez and Zeynep Aycan (2007) ‘Cross-cultural Organizational Behavior’, Annu. Rev. Psychol. 58: 479-514.

Gold Brunson, Julianne and Scott Lawrence (2002) ‘Impact of Sign Language Interpreter and Therapist Moods on Deaf Recipient Mood’, Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 33(6): 576-580.

Gold Brunson, Julianne (2009) ‘Impact of Deaf Client and Therapist Moods on Sign Language Interpreter Recipient Mood’, PhD dissertation, The University of North Carolina at Greensboro.

Greene, Terry R. and Helga Noice (1988) ‘Influence of Positive Affect upon Creative Thinking and Problem Solving in Children’, Psychological Report, 63: 895-898.

Grol, Maud, Ernst HW Koster, Lynn Bruyneel and Rudi De Raedt (2014) ‘Effects of Positive Mood on Attention Broadening for Self-related Information’, Psychological Research, 78(4): 566-573.

Hansen, Gyde (2008) ‘The Dialogue in Translation Process Research’, Paper presented at the XVIII FIT World Congress, Shanghai, China.

Hubscher-Davidson, Séverine (2009) ‘Personal Diversity and Diverse Personalities in Translation: A Study of Individual Differences’, Perspectives: Studies in Translatology, 17(3): 175-192.

Hubscher-Davidson, Séverine (2011) ‘A Discussion of Ethnographic Research Methods and their Relevance for Translation Process Research’, Across Languages and Cultures, 12(1): 1-18.

Hubscher-Davidson, Séverine (2013) ‘The Role of Intuition in the Translation Process: A Case Study’, Translation and Interpreting Studies, 8(2): 211-232.

Hubscher-Davidson, Séverine (2016) ‘Trait Emotional Intelligence and Translation: A Study of Professional Translators’, Target, 28(1): 132-157.

Isen, Alice M. (1984) ‘The Influence of Positive Affect on Decision Making and Cognitive Organization’, in Thomas C. Kinnear (ed) NA - Advances in Consumer Research, Provo: Association for Consumer Research, 11: 534-537.

Isen, Alice M. (1987) ‘Positive Affect, Cognitive Processes and Social Behavior’, in Leonard Berkowitz (ed) Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 20: 203–253.

Isen, Alice M. (1999) ‘Positive affect and creativity’, in Sandra Russ (ed.) Affect, Creative Experience, and Psychological Adjustment, London/Philadelphia: Brunner/Mazel, 3–17.

Isen, Alice M. (2008) ‘Affect Influences Decision-Making and Problem Solving’, in Michael Lewis, J. M. Jeannette Haviland-Jones and Lisa Feldman Barrett (eds) Handbook of Emotions, New York: The Guilford Press, 548-573.

Jääskeläinen, Riitta (1999) Tapping the Process: An Explorative Study of the Cognitive and Affective Factors Involved in Translating, Joensuu: Joensuun Yliopisto.

Kucera, Dalibor and Jiri Haviger (2012) ‘Using Mood Induction Procedures in Psychological Research’, Procedia – Social and Behavioural Sciences, 69: 31-40.

Laukkanen, Johanna (1996) ‘Affective and Attitudinal Factors in Translation Process Research’, Target, 8(2): 257-274.

Lehr, Caroline (2013) ‘Influences of Emotion on Cognitive Processing in Translation – A Theoretical Framework and Some Empirical Evidence’, Translation Process Research Conference, Aston University.

Lehr, Caroline (2014) ‘The Influence of Emotion on Language Performance: Study of a Neglected Determinant of Decision-Making in Professional Translators’, PhD dissertation, University of Geneva.

Martin, Leonard L., David W. Ward, John W. Achee and Robert S. Wyer (1993) ‘Mood as Input: People have to Interpret the Motivational Implications of their Moods’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64(3): 317-326.

Martin, Leonard L. and Gerald L. Clore (2001) Theories of Mood and Cognition: A User’s Guidebook. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Martin, Elizabeth A. and John G. Kerns (2011) ‘The Influence of Positive Mood on Different Aspects of Cognitive Control’, Cognition and Emotion, 25(2): 265-279.

Muñoz Martín, Ricardo (2014) ‘A Blurred Snapshot of Advances in Translation Process Research’, MonTI, 1: 49-84.

Pourtois, Gilles, Antonio Schettino and Patrik Vuilleumier (2013) ‘Brain Mechanisms for Emotional Influences on Perception and Attention: What is Magic and What is Not', Biological Psychology, 92(3): 492-512.

Robinson, Jennifer L., and Heath A. Demaree (2007) ‘Physiological and Cognitive Effects of Expressive Dissonance’, Brain and Cognition, 63(1): 70-78.

Robinson, Jennifer L., and Heath A. Demaree (2009) ‘Experiencing and Regulating Sadness: Physiological and Cognitive Effects’, Brain and Cognition, 70(1): 13-20.

Rojo López, Ana (2014) ‘The Emotional Impact of Translation: A Heart Rate Study’, The Journal of Pragmatics, 7: 31-44.

Rojo López, Ana and Marina Ramos Caro (2016) ‘Can Emotion Stir Translation Skill?’ in Ricardo Muñoz Martín (ed.) Reembedding Translation Process Research, Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 107-129.

Schwarz, Norbert (1987) Mood as Information, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag.

Schwarz, Norbert (2000) ‘Emotion, Cognition, and Decision Making’, Cognition and Emotion, 14: 433–440.

Schwarz, Norbert (1990) ‘Feelings-as-Information: Informational and Motivational Functions of Affective States’, in Edward Tory Higgins and Richard M. Sorrentino (eds), Handbook of Motivation and Cognition: Foundations of Social Behaviour, New York: The Guildord Press, 527–561.

Schwarz, Norbert (2002) ‘Situated Cognition and the Wisdom of Feelings: Cognitive Tuning’, in Lisa Feldman Barrett and Paul Salovey (eds.) The Wisdom in Feelings, New York: The Guilford Press, 144-166.

Schwarz, Norbert (2012) ‘Feelings-as-Information Theory’, in Paul A. M. Van Lange, Arie W. Kruglanski and Edward Tory Higgins (eds), Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology, London/Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications Ltd, 289-308.

Watson, David (2000) Mood and Temperament, London/New York: The Guilford Press.

Westermann, Rainer, Kordelia Spies, Günter Stahl and Friedrich W. Hesse (1996) ‘Relative Effectiveness and Validity of Mood Induction Procedures: A Meta-Analysis’, European Journal of Social Psychology, 26: 557-580.

Zadra, Jonathan R. and Gerald L. Clore (2011) ‘Emotion and Perception: The Role of Affective Information’, Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science, 2(6): 676-685.

Appendix 1 – Mood Measure

Instructions: please circle a number on the scales to indicate your response to each question.

1. On a scale of 1 (not at all) – 10 (very much), how positive do you think the video was?

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

2. On a scale of 1 (not at all) – 10 (very much), how negative do you think the video was?

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

3. On a scale of 1 (not at all) - 5 (very much) rate the extent to which the following adjectives match your current mood.

Happy 1 2 3 4 5

Sad 1 2 3 4 5

Pleased 1 2 3 4 5

Gloomy 1 2 3 4 5

Satisfied 1 2 3 4 5

Miserable 1 2 3 4 5

Appendix 2 – Source Text

Guide de Paris mystérieux

Paris est une ville mystérieuse. Rien n’est plus mystérieux que Paris. Il n’y a qu’à voir la Tour Eiffel promener ses gros yeux sur la ville pour sentir qu’il se passe des choses. Lesquelles? On ne sait pas trop, mais c’est très inquiétant. La Seine est noire et roule une eau sale. La lune est pompeuse ou fugitive, au hasard des arrondissements. Elle étale sa lueur glacée sur l’Esplanade des Invalides; ailleurs elle passe en 15 secondes tant le ciel est étroit. Elle éclaire d’un rayon oblique le tombeau des poètes, Baudelaire, Henri Heine, ceux d’Abélard et d’Héloïse, qui furent si malheureux et si intelligents (je tiens la chose de ma femme de ménage). Autant de fantômes, autant de mystères. Encore faut-il vouloir les voir. Wilde assurait qu’ «un gentleman ne regarde jamais par la fenêtre». Il habitait alors Quai Voltaire. Moins de préjugé aristocratique lui aurait permis de s’étonner. Il était surpris de voir les arrondissements se succéder en escargot, et la Seine couler d’est en ouest, ce qui la met a deux pas de l’Océan, et fait de Paris l’un des plus grands de nos ports de mer. Caprices de la nature et hasards de l’Histoire semblent s’être ainsi donné le mot pour faire éclore et conserver mystérieusement l’originalité de Paris.

Source : Lallemand-Rietkötter, A. (1972). La langue française par la presse: Textes et exercices. Hueber Hochschulreihe 14. München: Hueber.

Appendix 3 – Assessment Sheet

Participant number:

On a scale from 1 (very poor) to 5 (excellent), please rate how you felt this participant handled the following aspects in their translation:

|

1 2 3 4 5 |

|

A. Stylistic Features, e.g. tone/register |

|

B. Grammar |

|

C. Creativity, i.e. imagery/expressions/idioms |

|

D. Terminology/cultural items |

|

E. Loyalty to ST |

|

F. Consideration of wider context |

|

G. Overall coherence of translation |

What mark (out of 100) would you give the student for this translation?

Overall/additional comments:

[1]The search results included references to the Moodle online learning environment, and to the linguistic feature of verbs known as grammatical mood.

[2] What constitutes ‘positive’ and ‘negative’ emotions will be discussed in further detail in the next section.

[3]It must be noted that there is a fundamental distinction made by mood researchers between positive and negative affective experience, the former comprising feelings of joy, energy, enthusiasm, and alertness, and the latter comprising feelings of nervousness, sadness, irritation, and guilt (Watson 2000:33). Despite this distinction in the literature, the authors acknowledge that moods range on a continuum from pleasurable to unpleasurable feeling states.

[4]It has been acknowledged that restricting a video clip’s effect to one specific emotion is challenging, and that “some video manipulations can enhance more than one specific affective state at the same time” (Cohen et al. 2008). Nevertheless, video clips are said to be the most effective means to manipulate affect (Westermann et al. 1996) and it was felt that, if other likely emotions such as anger or fear were enhanced alongside sadness, these would still pertain to the intended negative affective state.

[5]As previously suggested, providing explicit task instructions has been shown to encourage a detail-oriented processing style. Admittedly, it could be argued that not providing a brief may have encouraged a global processing style in the experiment. The study could usefully be replicated with a brief, to see if this makes a difference to the results.