January 2016 Issue

Read, Comment and Enjoy!

Join Translation Journal

Click on the Subscribe button below to receive regular updates.

Speaking speed vs. Consecutive Interpreting speed A Case of English-Persian

- Details

Abstract

The aim of the present paper is to examine the relationship between the Interpreters' Speed of Speaking in their Mother Tongue (i.e. Persian) andthe Speed oftheir Consecutive Interpreting (i.e. from English to Persian), and to take an step for finding a general pattern regarding other languages. 40 Persian speaking M.A students served as participants of the study. To test their speaking speed in Persian, the participants were asked to talkabout their major, and instructors for afewminutes. To test their interpreting speed, they were asked to interpret a recorded text into Persian consecutively. The whole process was recorded, and transcribed by the researcher. The speed of their speaking, and interpretingwere calculated on the scale of words per minute (WPM). Finally the correlation coefficientbetween two variables was calculated using Pearson’s correlation coefficient,which turned out to be 0.44. It is concluded that there is a significant positive relationship between the variables, that is, those who speak fast in Persian, are likely to interpret fast from English into Persian, or the speed of interpreters’ interpreting is almost the same as that of their speaking, and it is likely to guess the speed of consecutive interpreting by considering the speed of speaking. The findings can be supplemented with other studies in different languages to come to a general pattern which is useful for interpreter training classes.

Key Terms: Speed, Speaking, Consecutive Interpreting, Mother Tongue

Introduction

As Herman (1956) argues, interpreting has been applied at different parts of the world during the history, specially, in ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome. But the recognition of Interpreting as a field of study is relatively new, according to Pochhacker and Shlesinger (2002) while interpreting as a form of mediating across boundaries of language and culture has been instrumental in human communication since earliest times, its recognition as something to be studied and observed is relatively recent.Pochhacker (2004) believes that, in addition to scientists like Barik, Gerver and Goldman-Eisler who took a great step toward improving the interpretation, there are a few other personalities with a professional background who have worked toward establishing the study of interpreting as a subject in academia. So carrying out an empirical study in this field is among the objectives of the present study to gain a better understanding and practice of interpreting.

Speech rate/speed is the term given to the speed at which you speak. It's calculated in the number of words spoken in a minute. A normal number of words per minute (wpm) can vary hugely. Speaking rate has been found to be related to many factors: individual, demographic, cultural, linguistic, psychological and physiological. Quené (2005) found that speaking rate depends mainly on utterance length.

Roach (1998) argues about our judgements regarding how quickly someone is speaking, just by listening, but it is not at all easy to work out what we base these judgements on. Speakers of some languages seem to speak so fast, while other languages sound rather slow, and some languages may stand between these extremes. These judgements may turn out to be false after carrying out scientific studies, that is, the speed of speaking cannot be judged by mere listening. We need to look for appropriate ways to measure how quickly someone is talking. In measuring speech, we can give someone a text to read, or a speaking task such as describing their experience e.g. their last holiday, and count how many words they produce in a given time (per minute or second). Most studies of speaking have found it necessary to make two different measurements of the rate at which we produce units of speech: the rate including pauses and hesitations, and the rate excluding such things.Li (2010) states that it is widely recognised that a rate between 100 and 120 words per minute (wpm) is optimal for English speeches, although the figure may differ for different speech types.Galli (1990) studies the effects of speech rate with three professional interpreters translating between English and Italian, at speeds ranging from 106 to 156 words per minute. According to Galli speech rate correlated with an increase in omissions and mistakes. Shlesinger (2003) conducted an experiment with sixteen professional interpreters who translated the same six source texts twice, in two sessions, with an interval of three weeks. The source texts were presented at two different speeds: 120 and 140 words per minute. In other words, each interpreter translated each text at two different presentation speeds. Shlesinger attributes this to the fact that the higher speed allows less time for source text items to decay. Chernov (2004) shows that the interpreter’s speed does not increase proportionally with the speaker’s. In fact, as if ‘fighting’ the speaker’s accelerating pace, the interpreter brings her own rate of speaking down to 71%, 73%, and 74% of the rate of the SL, while her speech approaches the speaker’s own most closely (87%) at the normal or optimal input of 120 wpm. Laver (1995) states that, the terms usually used are speaking rate and articulation rate. Tauroza and Allison (1990) measured words per minute, syllables per minute and syllables per word in different styles of spoken English and found substantial differences. Ofuka (1996) argues that, it is quite possible that some languages make more use of pauses and hesitations than others, and our perception of speed of speaking could be influenced by this. Oleron and Nanpon (1965) studied the delivery rate, number of words, and their relation to simultaneous interpreting in German-French, French-Spanish, English-French, and French- English pairs. Similar study, with focus on speed in second language (English), and the quality of consecutive interpreting, has been carried out by Rostami (2009). Some languages have been studied, but so many others needs to be investigated, not only regarding their speed of delivery, and similar features, but also their relation with interpreting, either simultaneous or consecutive.

Speed in interpreting is affected by different factors, some of which have been introduced by scholars, knowing them can be helpful to improve interpreter training classes, and to increase the quality of interpreting and even speed up the process of interpreting in circumstances under which the interpreters have to interpret as fast as possible to save the time.

Pochhacher (2004) argues that, ‘interpreting’ need not necessarily be equated with ‘oral translation’ or, more precisely, with the ‘oral rendering of spoken messages’. Kade (1968) defines interpreting as a form of translation in which the source language text is presented only once and thus cannot be reviewed or replayed, and the target- language text is produced under time pressure, with little chance for correction and revision.

The present study aims at carrying out an empirical investigation for finding the correlation between consecutive interpreting speed and Persian speaking speed hoping the results to be applied in real practice of interpreting, specially, for selecting appropriate candidates for interpreter training programs. Among the other objectives of this study is taking a step to find a general pattern for the relationship between interpreting and speaking speed, which is really helpful for interpreter training programs around the world.

1. Method

1.1. Participants

In order to carry out this research, the researcher involved 40 Iranian Persian speaking M.A students of English translation (male and female, and with no age limitation). Participants had familiarity with Interpreting, that is they had passed interpreting courses at university and practiced it. The researcher conducted an interview in English, to choose these participants who were proficient enough for taking part in research. The researcher set the score of 7out of 10, as a cut point. In addition to the researcher two other raters scored the participants’ speaking test. The final score was the average score of three raters, those who received at least 7, could pass the test and serve as participantss of the study. This test helped the researcher to choose the participants who were suitable for research regarding listening, speaking, fluency and accuracy in English Language.

1.2. Instrumentation

Two tests were designed by the researcher as the instruments of this study; one for assessing the participants’ speed of speaking in their mother tongue (Persian), and the other one for evaluating the speed of their consecutive interpreting (from English to Persian). Barik's formula was used for calculating the speed of speaking and interpreting:

Number of words

Speaking speed = --------------------------

Time (seconds)

(Barik, 1973)

60 seconds = 1 minute used as the unit of speaking and interpreting speed. Word per minute (WPM).

The researcher used SPSS, version 16 to calculate the correlation coefficient, and the inter-rater reliability.

1.3. Test of Speaking in Mother Tongue (Persian)

The participants were asked to introduce themselves, and talk about their, major, and instructors in Persian for a few minutes. The topic was general, and didn’t require any specific knowledge.

1.4. Test of Consecutive Interpreting

To test the speed of consecutive interpreting, the researcher asked the participants to interpret a recorded English text into Persian consecutively. Since the researcher wanted to check their speed of interpreting not their technical knowledge, their vocabulary proficiency or any other factor, the chosen text didn’t have any technical vocabulary. The researcher played the recorded text aloud, and after each pause, the participants interpreted it consecutively, they could take a note if needed. The length of sentences between two pauses, were the same for the whole participants.

1.5. Procedure

First the researcher provided the participants with some information about the task and after that under no circumstances the text was replayed or stopped. Then the participants were asked to talk about the above mentioned topic for some minutes in Persian, and finally after a few minutes the researcher played the recorded English text, and the participants interpreted it into Persian after each pause.

All the speaking and interpreting were recorded by the researcher using a voice recorder, and the work of each interpreter was then transcribed. The researcher counted the number of words, and calculated the time it took for every participant to say that number of words using a chronometer. In order to increase the reliability of analyzing the work of consecutive interpreting and speaking, the researcher listened to the recorded texts several times in order to transcribe them with a high precision. This study had two other raters in order to have more accurate results.

1.6. Data Analysis

1.6.1. Analyzing the Speaking and Interpreting Speed

After data collection, in order to calculate the speed of speaking in Persian, the researcher carefully listened to and transcribed the first minute speaking task of each participant. Great effort was put on this task, because any ignored word might influence the result of the study. No word was omitted - even repeated ones – because it took time to produce them. Then the researcher and the other raters counted the number of words.

After counting the number of spoken words the researcher had to measure the exact time it took for each participant to utter that number of words. So the recorded speaking tasks were replayed and listened to again. Here the researcher used a chronometer. When the participants began to speak, the researcher started the chronometer, and after passing one minute, the chronometer was stopped.

For calculating the speed of speaking in Persian the researcher divided the number of spoken words by the time it took to utter them. ‘60 Seconds = 1 minute’ was used as the unit of time. The WPM (words per second) scale used as follow:

Number of words

Speaking speed = --------------------------

Time (seconds)

(Barik, 1973)

The above stages were carried out again to calculate and analyze the interpreting speed.

1.7. Calculating the Correlation Coefficient

The researcher collected data from phases 1 and 2, in order to calculate the correlation coefficient between two variables, with the ultimate goal of understanding whether there is any significant relationship between the variables or not.

2.1. Descriptive Data

2.1.1. Choosing the Appropriate Participants

As it was mentioned earlier, to choose the proficient participants, the researcher carried out an interview with M.A students in English and recorded the interviews, table 1, shows the scores given by three raters and the average scores. By getting the minimum score of 7, these students could take part in research.

|

Average Score |

Scores from rater 3 |

Scores from rater 2 |

Scores from rater 1 |

Subjects |

|

9.83 |

10 |

10 |

9.5 |

1 |

|

9.66 |

9.5 |

10 |

9.5 |

2 |

|

7.5 |

8 |

7 |

7.5 |

3 |

|

8 |

8.5 |

7.5 |

8 |

4 |

|

9.33 |

9.5 |

9 |

9.5 |

5 |

|

9 |

9 |

9 |

9 |

6 |

|

9 |

8.5 |

9.5 |

9 |

7 |

|

8 |

8.5 |

7.5 |

8 |

8 |

|

8.66 |

9 |

8.5 |

8.5 |

9 |

|

7.83 |

8 |

7.5 |

8 |

10 |

|

7.5 |

7.5 |

7 |

8 |

11 |

|

9.66 |

9.5 |

9.5 |

10 |

12 |

|

7.16 |

7.5 |

8 |

6 |

13 |

|

8.5 |

8 |

9 |

8.5 |

14 |

|

9.5 |

10 |

9.5 |

9 |

15 |

|

8.33 |

8.5 |

8 |

8.5 |

16 |

|

9.5 |

9.5 |

10 |

9 |

17 |

|

7.83 |

7 |

8 |

8.5 |

18 |

|

8.5 |

8.5 |

8 |

9 |

19 |

|

8.5 |

9 |

7.5 |

9 |

20 |

|

9.83 |

9.5 |

10 |

10 |

21 |

|

7.33 |

7.5 |

8 |

6.5 |

22 |

|

8.5 |

8.5 |

8.5 |

8.5 |

23 |

|

8.83 |

8 |

9.5 |

9 |

24 |

|

8.5 |

9 |

8.5 |

8 |

25 |

|

8.16 |

9 |

7 |

8.5 |

26 |

|

9 |

9 |

9 |

9 |

27 |

|

8.5 |

8 |

8.5 |

9 |

28 |

|

8.66 |

8.5 |

9 |

8.5 |

29 |

|

8.83 |

9 |

9 |

8.5 |

30 |

|

8.66 |

8.5 |

8.5 |

9 |

31 |

|

8.5 |

8.5 |

8 |

9 |

32 |

|

8.33 |

8 |

8.5 |

8.5 |

33 |

|

8.33 |

8.5 |

8.5 |

8 |

34 |

|

8.16 |

8.5 |

8 |

8 |

35 |

|

8.83 |

8.5 |

9 |

9 |

36 |

|

8.5 |

8 |

9 |

8.5 |

37 |

|

8.83 |

9 |

8.5 |

9 |

38 |

|

8 |

7.5 |

8.5 |

8 |

39 |

|

8.66 |

8.5 |

9.5 |

8 |

40 |

Table1 . Scores Given by 3 Raters and the Average Score

2.1.2. Inter-Rater Reliability

The correlations of the scores given by three raters were calculated using Pearson's correlation formula, then, the correlations were put in Spearman-Brown Prophecy Formula to calculate the inter-rater reliability, the formula is as follow:

rtt = 0.81

where, rtt= Inter-rater reliability A= Rater a rA,B= Mean

n= Number of raters B= Rater b

|

Rater 2 vs. Rater 3 |

Rater 1 vs. Rater 3 |

Rater 1 vs. Rater 2 |

|

|

0.506 |

0.644 |

0.627 |

Correlation |

Table 2. Correlation of the Scores Given by 3 raters

As the formula shows, the inter-rater reliability among the three raters including the researcher was calculated which turned out to be 0.81. This shows a high correlation, allowing the researcher to trust the scoring procedure.

2.1.3. Calculating the Interpreters' Speed of Speaking in their Mother Tongue

The participants' speed of speaking in their mother tongue (Persian) were calculated using Barik's formula. The data for the calculation of speaking speed obtained by this formula appears in table 3. Three raters including the researcher calculated the speaking speed to increase reliability.

|

Average Speed |

Calculated Speed by Rater 3 |

Calculated Speed by Rater 2 |

Calculated Speed by Rater 1 |

Subjects |

|

2.38 |

2.38 |

2.38 |

2.38 |

1 |

|

1.65 |

1.65 |

1.65 |

1.65 |

2 |

|

1.16 |

1.16 |

1.16 |

1.16 |

3 |

|

1.45 |

1.45 |

1.45 |

1.45 |

4 |

|

2.18 |

2.18 |

2.18 |

2.18 |

5 |

|

1.8 |

1.81 |

1.78 |

1.81 |

6 |

|

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

7 |

|

1.31 |

1.31 |

1.31 |

1.31 |

8 |

|

1.76 |

1.76 |

1.76 |

1.76 |

9 |

|

2.47 |

2.5 |

2.46 |

2.46 |

10 |

|

1.65 |

1.65 |

1.65 |

1.65 |

11 |

|

1.75 |

1.75 |

1.76 |

1.76 |

12 |

|

1.05 |

1.03 |

1.06 |

1.06 |

13 |

|

1.66 |

1.66 |

1.66 |

1.66 |

14 |

|

1.58 |

1.6 |

1.56 |

1.6 |

15 |

|

1.63 |

1.63 |

1.63 |

1.63 |

16 |

|

1.33 |

1.33 |

1.33 |

1.33 |

17 |

|

1.71 |

1.71 |

1.71 |

1.71 |

18 |

|

2.76 |

2.76 |

2.76 |

2.76 |

19 |

|

1.56 |

1.56 |

1.56 |

1.56 |

20 |

|

1.98 |

1.98 |

1.98 |

1.98 |

21 |

|

2.31 |

2.31 |

2.31 |

2.31 |

22 |

|

1.56 |

1.56 |

1.56 |

1.56 |

23 |

|

1.84 |

1.83 |

1.85 |

1.85 |

24 |

|

2.16 |

2.16 |

2.16 |

2.16 |

25 |

|

1.95 |

1.95 |

1.96 |

1.95 |

26 |

|

1.7 |

1.7 |

1.7 |

1.7 |

27 |

|

1.73 |

1.73 |

1.73 |

1.73 |

28 |

|

2.11 |

2.11 |

2.11 |

2.11 |

29 |

|

1.91 |

1.91 |

1.91 |

1.91 |

30 |

|

1.61 |

1.61 |

1.61 |

1.61 |

31 |

|

1.88 |

1.88 |

1.88 |

1.88 |

32 |

|

1.46 |

1.46 |

1.46 |

1.46 |

33 |

|

1.23 |

1.23 |

1.23 |

1.23 |

34 |

|

1.48 |

1.48 |

1.48 |

1.48 |

35 |

|

1.81 |

1.81 |

1.81 |

1.81 |

36 |

|

1.65 |

1.65 |

1.65 |

1.65 |

37 |

|

1.48 |

1.48 |

1.48 |

1.48 |

38 |

|

1.03 |

1.03 |

1.03 |

1.03 |

39 |

|

1.65 |

1.65 |

1.65 |

1.65 |

40 |

Table 3. Calculated Speed by 3 Raters and the Average Speed for Speaking in Mother Tongue (Persian)

As it can be seen all raters have come to the same conclusion.

2.1.4. Calculating the Interpreters' Speed of Consecutive Interpreting

The data for the calculation of interpreting speed obtained by Barik's formula appears in table 5.

|

Average Speed |

Calculated Speed by Rater 3 |

Calculated Speed by Rater 2 |

Calculated Speed by Rater 1 |

Subjects |

|

2.5 |

2.5 |

2.5 |

2.5 |

1 |

|

2.9 |

2.9 |

2.9 |

2.9 |

2 |

|

1.93 |

1.93 |

1.95 |

1.93 |

3 |

|

2.52 |

2.48 |

2.56 |

2.53 |

4 |

|

3.28 |

3.28 |

3.28 |

3.28 |

5 |

|

2.51 |

2.51 |

2.53 |

2.51 |

6 |

|

2.98 |

2.98 |

2.98 |

2.98 |

7 |

|

2.38 |

2.38 |

2.38 |

2.38 |

8 |

|

2.86 |

2.86 |

2.86 |

2.86 |

9 |

|

2.91 |

2.91 |

2.91 |

2.91 |

10 |

|

2.05 |

2.05 |

2.05 |

2.05 |

11 |

|

2.76 |

2.76 |

2.76 |

2.76 |

12 |

|

2.71 |

2.71 |

2.71 |

2.71 |

13 |

|

2.98 |

2.98 |

2.98 |

2.98 |

14 |

|

2.68 |

2.68 |

2.68 |

2.68 |

15 |

|

2.58 |

2.58 |

2.58 |

2.58 |

16 |

|

2.38 |

2.38 |

2.38 |

2.38 |

17 |

|

1.73 |

1.73 |

1.73 |

1.73 |

18 |

|

2.51 |

2.51 |

2.51 |

2.51 |

19 |

|

2.23 |

2.23 |

2.23 |

2.23 |

20 |

|

3.06 |

3.08 |

3.05 |

3.05 |

21 |

|

2.55 |

2.55 |

2.55 |

2.55 |

22 |

|

1.86 |

1.86 |

1.86 |

1.86 |

23 |

|

3.23 |

3.23 |

3.23 |

3.23 |

24 |

|

2.28 |

2.28 |

2.28 |

2.28 |

25 |

|

2.69 |

2.66 |

2.71 |

2.71 |

26 |

|

2.88 |

2.88 |

2.88 |

2.88 |

27 |

|

2.63 |

2.63 |

2.63 |

2.63 |

28 |

|

2.5 |

2.5 |

2.5 |

2.5 |

29 |

|

3.06 |

3.08 |

3.03 |

3.08 |

30 |

|

2.56 |

2.56 |

2.56 |

2.56 |

31 |

|

2.45 |

2.45 |

2.45 |

2.45 |

32 |

|

2.3 |

2.3 |

2.3 |

2.3 |

33 |

|

2.36 |

2.36 |

2.36 |

2.36 |

34 |

|

2.25 |

2.25 |

2.25 |

2.25 |

35 |

|

3.01 |

3.01 |

3.01 |

3.01 |

36 |

|

1.99 |

1.98 |

2 |

2 |

37 |

|

2.76 |

2.76 |

2.76 |

2.76 |

38 |

|

1.88 |

1.88 |

1.88 |

1.88 |

39 |

|

1.82 |

1.82 |

1.82 |

1.82 |

40 |

Table 4. Calculated Speed by 3 Raters and the Average Speed for Interpreting (from English to Persian)

2.1.5. Calculating Inter-Rater Reliability

The correlations of the calculated speed by three raters for interpreting ( from English to Persian) were calculated using Pearson correlation formula, table 6, then, the correlations were put in Spearman-Brown Prophecy Formula to calculate the inter-rater reliability, the formula is as follow:

rtt = 0.99

|

Rater 2 vs. Rater 3 |

Rater 1 vs. Rater 3 |

Rater 1 vs. Rater 2 |

|

|

0.996 |

0.998 |

0.999 |

Correlation |

Table 5. Correlation of the Calculated Speed by 3 Raters for Interpreting (from English to Persian)

As it can bee seen, the inter-rater reliability between the researcher and two other raters was calculated which turned out to be 0.99. This shows an optimum correlation allowing the researcher to trust the procedure.

2.1.6. Calculating the Correlation between two variables (Speed of Speaking in Persian and Speed of Consecutive Interpreting)

|

Persian |

Correlation Coefficient |

1.000 |

.442** |

|

|

Sig. (2-tailed) |

. |

.004 |

||

|

N |

40 |

40 |

||

|

Interpreting |

Correlation Coefficient |

.442** |

1.000 |

|

|

Sig. (2-tailed) |

.004 |

. |

||

|

N |

40 |

40 |

||

|

**. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). |

||||

Table 6. Spearman's Correlation (Persian vs. Interpreting)

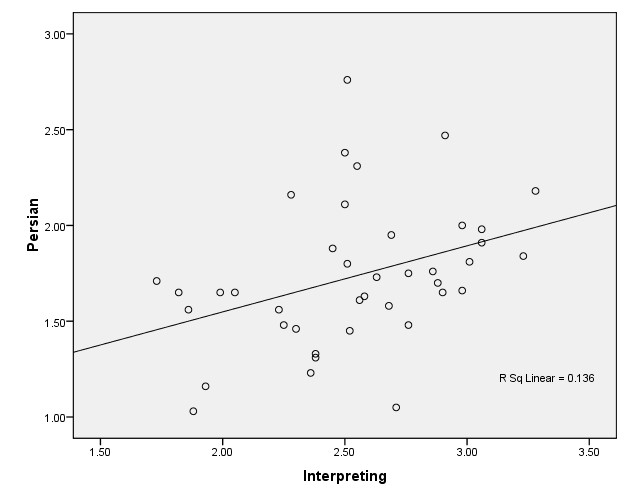

An analysis using Pearson’s correlation coefficient shows the relationship between two variables, it is interpreted as significant positive relationship, r = 0.44.

The following diagram shows the correlation between the variables:

Diagram 1. Distribution of the Two Variables (Persian vs. interpreting)

Diagram 1. Distribution of the Two Variables (Persian vs. interpreting)

3. Conclusions and Discussion of the Findings

According to the calculated correlation (r = 0.44), there was a significant positive relationship between the two variables.Based on the findings of this study, it can be concluded that, the interpreters' speed of speaking in their mother tongue (Persian) can be used as one of the criteria for selecting students for interpreter training institutes, that is, the interpreters who speaks fast in their mother tongue (Persian), are likely to interpret fast or almost at the same speed as they speak. Simply put, the interpreting pace can be guessed, by considering the interpreter's pace of speaking in mother tongue. The speaking and interpreting processes are interrelated in this language pair. From other perspective there is an almost similar speed between speaking in Persian and consecutive interpreting from English into Persian.

4. Theoretical and Pedagogical Implications

As it was reviewed earlier, the interpreting studies is a relatively new academic field of study, and it's not still an independent discipline in many countries. The daily increasing need for the professional interpreters, calls for persistent researchers to carry out research in this field, in order to understand more about interpreting process, and improve the quality of interpreting.

One of the areas which is helpful for improving interpreting training and qualities is to find out the relationship between languages speed and interpreting speed into or out of languages. Such findings provide us with a better understanding of the process of interpreting and drawing a general pattern for such process.

In this study the researcher intended to take a step toward understanding more about the nature of interpreting and its speed and its relationship with Persian language speaking speed, which can be applied in improving the teaching and learning of the interpreting, either at universities or in interpreter training institutes .Among the other intentions of the present study, it can be referred to paving the way for other empirical studies regarding other language pairs.

An analysis using Pearson correlation coefficient supported significant positive relationship between speed of speaking in Persian and speed of consecutive interpreting (from English into Persian) r = 0.44, that is, those who speak fast in Persian are likely to interpret fast from English into Persian, , or the speed of interpreters’ interpreting is almost the same as their speed of speaking. The findings can be applied by interpreter training institutes for choosing appropriate would be interpreters.

The findings are also may motivate other researchers to carry out more extensive studies using professional interpreters to evaluate correlation between these or other variables. Other researchers using other languages at different settings can follow the same or similar procedure to come to conclusion regarding such relationships. Studying a large number of languages regarding their correlation with interpreting (simultaneous or consecutive), can provide us with general patterns and scientific findings, which are invaluable for understanding, teaching, testing, and practice of interpreting.

Bibliography

Barik, H. C. (1973). "Simultaneous Interpretation: Temporal and Quantitative Data," Language and Speech 16 (3): 237-70.

Chernov, G. V. (2004). Inference and Anticipation in Simultaneous Interpreting. A probability-prediction model. Amsterdam/ Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Galli, Cristina (1990). "Simultaneous Interpretation in Medical Conferences: A Case-Study". In L.Gran & C. Taylor (Eds.), Aspects of applied and experimental research on conference interpretation. Udine: Campanotto Editor, pp. 61–82.

Hermann, A. (1956). “Dolmetschen im Altertum. Ein Beitrag zur antiken Kultur geschichte,” in K. Thieme, A. Hermann and E. Glasser, Beitrage zur Geschichte des Dolmetschens, Munichen: Isar Verlag, pp. 25-59.

Kade, O. (1968). "Zufall und Gesetzmabigkeit in der Ubersetzung", Leipzig: Verlag Enzyklopadie.

Laver, J. (1995). Principles of Phonetics, Cambridge University Press.

Mahmoodzadeh, K. (2003). "Time: the Major Difference between Translating and Interpreting," in Translation Studies, 1(1), 33-43.

Miremadi, S. A. (2005). Theoretical Foundations and Principles of Translation, Tehran: SAMT Publications.

Munday, J. (2001). Introducing Translation Studies Theories and Applications, London and New York: Routledge.

Ofuka, E. (1996). Acoustic and Perceptual Analyses of Politeness in Japanese Speech, unpublished Ph.D. thesis, University of Leeds.

Oleron P. (1992). “Autobiographie,” in F. Parot and M. Richelle (eds) Psychologues de langue francise. Autobiographies, Paris: Press Universitaires de France, pp. 135-59.

Pochhacker, F. (2004). Introducing Interpreting Studies, London and New York: Routledge.

Pochhacker, F. and Shlesinger, M. (2002). The Interpreting Studies Reader, Routledge, London and New York.

Quené, H. (2005). “Modeling of between-speaker and within speaker

variation in spontaneous speech tempo", INTERSPEECH-2005, 2457-2460.

Richards, J. C. (2005). Tactics for Listening, Oxford University Press.

Roach, P. (1998). “Some Languages are Spoken More Quickly than Others” in 'Language Myths', (eds.) L. Bauer and P. Trudgill, Penguin, pp. 150-8.

Rostami, M. (2009). On the Relationship between Interpreters' Speed of Speaking in Their Second Language and the Quality of Their Consecutive Interpreting. Unpublished M.A Thesis. Islamic Azad University Tehran Central Branch.

Shlesinger, M. (2003). "Effects of Presentation Rate on Working Memory in Simultaneous Interpreting". In The Interpreters’ Newsletter. Vol.12, pp. 37–49.

Tauroza, S. and Allison, D. (1990). ‘Speech rates in British English’, Applied Linguistics, 11, pp.90-105.

Venuti, L. (2000). The Translation Studies Reader, (ed.), London and New York: Routledge.