October 2015 Issue

Read, Comment and Enjoy!

Join Translation Journal

Click on the Subscribe button below to receive regular updates.

An Analysis of a New Contemporary Teaching-Learning Strategy in Translation Studies: Distance Online Translator Training

- Details

- Written by Elham Rajab Dorry

Abstract

As the translation market expands, translator training and translation technology have become hot topics. The trends lean towards online distance learning and curriculum development to train translators in the skills needed for an increasingly electronic market. The use of electronic tools in training programs, in this case, in the training of translators, is close to what is elsewhere known as ‘open and distance learning’ (ODL), or more generally with distance learning tout court. In this paper we try to show how new technologies can improve not only the professional standard of translator trainee, which includes the acquisition of skills like the use of translation memories, databases, and the Internet as information sources, but also analysis of how they can become a pedagogical tool to achieve crucial skills. Historical background of distance learning and different aspects of it is explored. For analyzing distance online translator training advantages and disadvantages of it is shown.

Key words: Distance Online Translator Training,Open and Distance Learning, Translation, Translator Training.

1. Introduction

Every translation activity has one or more specific purposes and whichever they may be; the main aim of translation is to serve as a cross-cultural bilingual communication vehicle among peoples. In the past few decades, this activity has developed because of rising international trade, increased migration, globalization, the recognition of linguistic minorities, and the expansion of the mass media and technology.

Translator training is a subject which has been widely discussed and many diverse approaches have been put forward. However little research has been done to investigate translation training courses and even less data has been gathered to validate any claims as to the effectiveness or pedagogical value of these approaches to translator education (Askehave 2000).

Improving pedagogy is the constant aim of any diligent instructor, and therefore of any translation instructor, too. The requirements and the conditions of modern life, as well as the impact of globalization, are challenges for teaching, as learners need to learn new skills in order to be able to confront them. The last half of the twentieth century was characterized by revolutions in information and communication, and technology that have influenced numerous professions, including translation. The new technology has made translators’ work easier, but, in order to meet market needs, information and communication technology must occupy their rightful place in translator training (Archer, 2002). The development of new information and communication technology influences an ever-changing professional reality that requires almost constant updating.

If we look throughout some years ago, can conceive some truth about translator training:

In 1972, James Holmes published for the first time his canonical essay on the nature of Translation Studies.James. S. Holmes’ seminal ‘The Name and Nature of Translation Studies’ (1972) set out to orient the scholarly study of translation. It put forward a conceptual scheme that identified and interrelated many of the things that can be done in translation studies, envisaging an entire future discipline and effectively stimulating work aimed at establishing that discipline. He is known to distinguish between ‘theoretical translation studies or translation theory’ and teaching as a ‘technique in foreign-language instruction’ and as ‘translator training’ (1988).

2. The Holmes Map of Translation Studies: Translator Training

In 1972, James Holmes published for the first time his canonical essay on the nature of Translation Studies. Holmes’ paper “The Name and Nature of Translation Studies” was reported at the Third International Congress of Applied Linguistics in Copenhagen in 1972, published as proceedings in 1978, and as a book in 1988, posthumously.

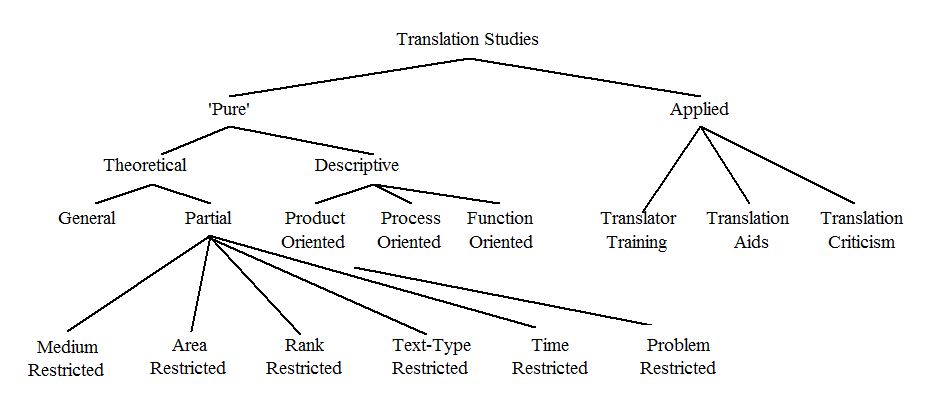

Holmes’ categories were simple, scientifically framed, and hierarchically arranged: ‘Applied’ was opposed to ‘Pure’, the latter was broken down into ‘Theoretical’ and ‘Descriptive’, then, Descriptive branch of Translation studies (DTS) is divided by Holmes into three major kinds of research, “distinguished by their focus”: Product-oriented (PT), Function-oriented (FN), and Process-oriented (PS)” (ibid: 72), (Figure 1).

Holmes’ conception of translation studies (Toury 1991, P. 181)

The third branch beside its theoretical and descriptive branches is the branch of applied translation studies. The principal fields within this branch are Translator Training, Translation Aids, and Translation Criticism (Holmes, 1972, 1988). Ever since 1972, when James Holmes published for the first time his essay on the nature of Translation Studies, a few voices have raised the complaint that what Holmes termed Applied Translation Studies, and specially the teaching of translation, has made little progress if any. Thus, Amparo Hurtado Albir said in her prologue to Allison Beeby on his work on the teaching of translation from Spanish into English said: (Beeby, 1996).

Both theoretical and descriptive translation studies have multiplied in recent years but perhaps the advances have been fewer in applied translation studies (translation training, translation aids, translation criticism and evaluation).

Others, like Mayoral Asensio have declared that Translation Studies cannot at present offer enough means or tools for translation teacher to enhance their methodology so as to help students find better solutions for solving translation problems or to instruct translators more effectively ( Asensio, 2001, p.16).

Be that as it may, new avenues of research and additional momentum are always to be welcomed in any discipline. Stagnation in educational translation theory can be damaging for students and teaching institutions. The way we see it, teachers and theorists of translation pedagogy should always be on the lookout for new didactic strategies and methodologies in a continuous effort to enhance the teaching and learning process. The main theoretical principles of distance education will then be linked to translation education in particular and what is being done now in teaching translation from a distance.

In exploring the potential use of technologies as a medium for learning, authors and academics have looked at the challenges for instructors, and learners. Before we proceeded to evaluation of distance online translator training, we needed to come to a common understanding about aspects of quality and the different perspectives available in the design of online and distance learning environments.

3. Some Historical Background on Distance Learning

In Ancient times distances certainly seemed greater and more difficult to surmount than are today. The seekers of knowledge had to travel to the source in order to get it or, like the traveling rhetoricians and old sophists of the Classic world who walked far and wide around Greece taking their vis persuadendi (skill or faculty of persuading) to villages and cities, instructing students here and there for a fee, the source would come to them. The distance was then bridged by the teacher himself or, more often, by the student. Letters written by the wise and distributed slowly through the land to reach their destination and their readers' hands were also the earliest instances of distance teaching (Alcala, 2002).

The experts in distance education tend to sequence the various stages of the history of this teaching method by closely following the phases of development undergone by the means used therein. Hence, the means used to fill the separation existing between learner and teacher determine to a great extent the arrangement and study of the history of distance education (Aretio, 2001):

3.1.Correspondence Teaching

Laying aside the earliest examples of instructive correspondence of ancient and classical civilizations and later periods, the first known instance of a teaching correspondence course in the West dates back to 1728, when a Mr. Caleb Philipps, professor of short hand, published an advertisement in the Boston Gazette offering teaching materials and tutorials. He offered to teach his “art” to all who so desired in the Boston region (Graff, 1980).

However, the first testimony of an organized correspondence course in which there was bidirectional communication comes from England, in 1840, when Isaac Pitman initiated a short hand course, wherein he sent a passage of the Bible to students and these would send it back in full transcription. As a further instance we may recall the pioneering milestone in distance language teaching laid in 1856 by Charles Toussaint and Gustav Langenscheidt, who started up the first European institution of distance learning, the Institut Toussaint etLangenscheidt in Germany. This is the first known instance of the use of materials for independent language study. From those early stages, correspondence institutions appeared in the United States and other European countries (Alcala, 2002).

3.2. Multimedia Teaching

Here the term "multimedia" refers to the use of several means (media) to reach the students and provide instruction. According to Aretio, this stage is a product of the 1960s, especially around the key year 1969, when the British Open University was founded Printed materials are joined by audiotapes, videotapes, radio and TV broadcasts, telephone, etc. In this stage, the theorists of distance education focused their attention in the design and production of teaching materials and the interaction between learners and teachers took on a secondary role (Aretio, 2001, p. 50).

3.3. Telematic Teaching

Aretio (2001, p.101) dates the beginning of this third generation of distance teaching in the 1980s. This decade marks the arrival of modern telecommunications in the education scene. Computers increasingly became an everyday tool reaching more homes and institutions of higher learning. Computer aided teaching was the great development and integration was the key word: integration of technical and educational means and instruments. These are some of the features of the period:

Integration of media

Student-centered education

Synchronous (real time) communication between learner and teacher

Asynchronous (differed) communication is also possible

Multimedia systems (hypertexts, i.e., materials used)

3.4. Teaching through the Internet

This stage has received several names: fourth generation distance teaching, virtual campus, virtual teaching, flexible learning model, etc. It is the Internet age. The World Wide Web reveals itself as the great breakthrough. Teachers and learners can communicate faster and even in real time. But, as Aretio (2001) points out, the most important contribution of the arrival of the Internet has been the surmounting of one of the traditional obstacles of distance learning: the lack of two-way interaction or bidirectional communication. In traditional correspondence teaching, teachers had a hard time obtaining feedback from their students, quickly, promptly and directly.

The Internet has made a real communication flow in the teaching/learning process finally possible and has allowed teachers and learners to go a few steps further. In this vein, some authors are foreseeing the beginning of a fifth generation teaching or education (Taylor, 1999 and Ogata y Yano, 1997, quoted in Aretio, 2001, p 52). This future model has been referred to as the flexible intelligent learning generation, in which the computer would take the place of the teacher as tutor and mentor of distance learners and a completely automated response system. Thus, it would be possible to cut down costs for staff and faculty.

Before the evaluation of distance online translator training, we needed to come to a common understanding about different aspects and the perspectives available in the design of online and distance learning environments.

4. Different Aspects of Distance Online Learning

For a long time, distance learning by way of correspondence coerces was the only way to reach students who were physically separated from their instructor. With the arrival of the technologies that provide the variety of the media connecting students to instructors, peers and learning materials, distance learning today has to address the complexities of online learning environments and meet the demands online learning places on students and instructors.

Distance learning students have different motivations for leaning this way; they may prefer learning independently or they may face barriers of transportations, scheduling, and/or accessibility to services that prevent the participation in a traditional school. New technology makes new ways of learning possible. Today, distance learning brings together life-long learning theory with the idea of technology-based education over the last two decades (Kelly& Kennell & Sturn, 2002).

A new computer and communication technology has emerged together with the software application such as browsers and other clients; distance learning has become synonymous with learning online. However, while distance learning carries the interpretive baggage of its principal defining characteristic, i.e. the separation between the instructor and student, online learning is often too narrowly defined as “education and training delivered and supported by networks such as the Internet or intranets” (Kelly& Kennell & Sturn, 2002).Overall, it can be stated that online learning uses technology to breach the distance where there is a separation of student and instructor in time and space. The following statements best reflect our convictions about learning that online and distance learning environments should bring to life.

• Learning is distributed in that it “makes use of mixed or multimedia tools to bridge the distance between instructor and learner.” (Technology perspective)

• Learning is blended in that it “employs multiple strategies, methods, and delivery systems” including e-based and print-based resources. (Content perspective)

• Learning is flexible in that it “expands the choice on what, when, where, and how people learn. “(Learner perspective), (Kelly& Kennell & Sturn, 2002).

It is essential to recognize that most online and distance translator training today is and/or is recommended to be a mixture of distributed, blended, and flexible learning. From a student’s point of view, online learning environments can take different forms. Here are three scenarios that often come together in the design of online and distance learning environments:

4.1. Distributed Learning

Students’ study mostly using the Internet with learning materials and activities distributed using technology as a medium. Such programs may provide immediate learning activities, voice and/or text chat with instructors and students, recording and playback features, discussion boards to serve as meeting places, regular synchronous and/or asynchronous contact with an instructor, individualized learning plans, ongoing monitoring of student's progress, and telephone support.

4.2. Blended Learning

Students go to class and meet instructors and classmates face-to-face but they also learn independently using e-based or print-based resources depending on the best possible fit between the learning material and the technology medium. Computer-based learning and Web-based learning is offered as part of the learning experience to varying degrees. Students spend time on computers and have a lot of learning software available to them. They also have Internet connections and instructors build web-based learning into the process.

4.3. Flexible Learning

Students go to class and meet instructors and classmates face-to-face but they also complement this learning to a higher degree with web-based learning via an online component available to them outside of the classroom and scheduled hours. Students use the Internet to pick up assignments and documents, participate in discussion board rooms, take quizzes, check their grades, consult a calendar and do other things to help them with their learning.

5. Distance Online Translator Training

One of the major recent developments in the translation industry is the introduction of computer technology. It was shown that both students and teachers were aware of the need to familiarize themselves with the new translation technologies. The way translators work has changed: commissions arrive by email, and translators are expected to use the internet, electronic dictionaries, translation memory tools, electronic corpora and concordance software, etc. to increase the efficiency and quality of their work. In short, the set of basic skills required of a translator at the beginning of the Third Millennium looks very different from what it was only fifteen years ago.

In the past, what was required from a translator was essentially a good bilingual Linguistic competence, which included some knowledge of the foreign country’s culture. No experience in editing was necessary – agencies or publishers dealt with copyediting, proofing and formatting. Today the picture is completely different: a professional translator has to add literacy in computer technology to the set of skills necessary to tackle most modern-day translation jobs.

As far as the training of translators is concerned, research on the nature and development of translation competence has shown how part of this competence (what some scholars have referred to as translator competence) consists of procedural skills, many of which have to do with the way translators learn to interact with computers and digital resources. The introduction of electronic means of communication into the teaching-learning process has conferred special importance on virtual environments as pedagogy advances. The possibilities of these tools have not yet been sufficiently explored. The first reason is the lack of knowledge among instructors about how to merge their methodology with electronic tools. Pedagogy of translation in term of translator training is still quite neglected.

Assuming there is a need to revitalize the didactics of translation as a whole, the study and practice of distance education or distance translator training comes in as an exciting and promising laboratory for testing and developing innovative and effective training.

If one sees translation pedagogy as a thriving field of research and application of theoretical principles resulting from that research, a more careful consideration of the potential benefits of distance translator education cannot be overlooked, from a theoretical, practical, institutional and even economic point of view. With the growing presence of new technological means, the power for innovation broadens even more (Alcala, 2002).

6. Advantages of Distance Online Translator Training

Nowadays we witness great shifts in the field of teaching methods. Those shifts affect the way of teaching and learning as well as the basic rules that underlie it. For instance, learners become responsible for their own learning process, which is supposed to be a lifelong one, the contents taught should be closely related to the later professional environment, and learners must be enabled to achieve autonomous learning and self-assessment. The impact of the new technologies and globalization and internationalization is going hand in hand with each other. Society is now expecting the University to respond to those challenges. And it is just these new technologies that can help to adapt to a new pedagogy of open learning, where every learner can achieve the skills necessary for his or her profession in a time and a way that suits him.

Not only is teaching methodology changing, but also the roles, or even better, the functions of instructor and learner. As learners become the central agent of the learning process, they have to decide the content, the way and the sequence of it. Instructors are relegated to a role in the background, although they maintain their importance as tutors who guide the learners to the sources of factual knowledge, to the acquisition of knowledge, to the tools and strategies of autonomous learning, and who develop continuous assessment. In addition, learners shall mainly acquire learning strategies that help them to cope with problems outside the classroom, to work with others in a collaborative way and to construct knowledge together with them.

The introduction of electronic means of communication into the teaching-learning process has conferred special importance on virtual environments as pedagogy advances. If one sees translation pedagogy as a thriving field of research and application of theoretical principles resulting from that research, a more careful consideration of the potential benefits of distance translator education cannot be overlooked, from a theoretical, practical, institutional and even economic point of view. With the growing presence of new technological means, the power for innovation broadens even more (Alcala, 2002).Quality of teaching lies not only in the simple use of e-mail, the Internet and intranets. Some advantages of distance online translator training may be summarized as follows:

6.1. Necessary Communication Skills

Perhaps the most compelling reason is that professional translating increasingly involves the use of the electronic tools used in distance online training (email, attachments, websites,). Since students will have to use these tools in their professional life, they might as well get used to them in their training: if the medium is not quite the whole message, it is at least part of the competence to be acquired. The future of both translation and training would thus be to some degree pre-inscribed in the technology.

6.2. Tandem Learning

Another important factor supporting distance online training is the way it opens up possibilities for ‘tandem’ learning arrangements. This would involve, for example, an Iranian student in Iran working on a translation together with a British student in Britain. One student will have more competence in Persian than in English; the other will be better at English: together, the two should be able to combine their complementary competencies in such a way that they effectively teach each other a lot about languages, if not about translation as such. Tandem arrangements have been extensively promoted for the learning of second languages, where they quite obviously make the most sense. Yet they appear not to have risen above the experimental level in translator training, probably because they require significant degrees of inter-institutional organization, across political and cultural boundaries.

6.3. Student Demand

A third reason for distance online training is that there is a strong student demand for distance courses of this kind. The demand is mainly from mature-age students, mostly professionally employed, who want to gain skills of this kind or who are interested in obtaining a recognized qualification.

7. Disadvantages of Distance Online Translator Training

The possibilities of these tools have not yet been sufficiently explored. The first reason is the lack of knowledge among instructors about how to merge their methodology with electronic tools. Pedagogy of translation is still quite neglected. There has been no significant change since Király declared more than ten years ago that "there has also apparently been no attempt to apply general pedagogical principles to translation teaching. There has been little or no consideration of learning environment, learner-instructor roles, scope and appropriateness of teaching techniques, coordination of goal-oriented curricula, or evaluation of curriculum and instructor" (1995, p.11).

Distance online translator training is no immediate panacea for the new evident demands in translation courses. Those problems might be summarized as follows:

7.1. Investment of Resources

The most obvious drawback is that it takes considerable time and effort to set up a web based course, and even more time and effort to keep things running via email and chat. The investment of resources is on both the teaching and learning sides, and can be problematic for both. Instructors rarely have all the skills necessary to produce attractive and useful websites, and students also need time to master the basic tools of e-learning interaction.

7.2. Student Distress

Difficulties with the technology may lead to various kinds of ‘student distress’, especially in the initial stages of the learning process (Noriko & Kling, 2000). Not everyone is equally expert in basic internet skills; it takes time to learn how to use email efficiently; struggling alone with a computer can be a very isolating experience. The problems here are both social and linguistic

Linguistically, electronic words suffer famously from the lack of intonation, body language, hedging and back-channeling that make face-to-face contact a much richer and more subtle mode of communication. All these problems, however, are part and parcel of the electronic means of communication that students will have to master in the professional environment, in order to communicate with clients, fellow translators, or project managers. In a sense, the distress will come sooner or later, and in the training of translators it is probably best to meet and manage it as early as possible.

7.3. Heterogeneous Learning Communities

A more serious problem with e-learning stems from the tendency of the learning groups to be heterogeneous. Gone are the days when we could walk into a classroom full of students all aged 18 or 19 and all relatively fresh from secondary schools in our local region. As teaching space was extending electronically, learning groups will comprise a wide range of ages and cultural backgrounds. On other levels, though, one quickly runs into problems of unequal technical and linguistic competencies. One also discovers widely different cultural concepts about the underlying procedures of the learning process, in some cases complicated by seriously entrenched differences concerning the nature of translation (Pym, 2000).

The wider the physical space was covered, the more these cultural differences become apparent, and the more work have to be invested in making our basic concepts at once clear and open to negotiation.

7.4. Waning Motivation

A fourth drawback would be declining motivation among part-time students. This is a feature remarked virtually across the board in distance programs for mature-age students. For as much as one might expect students to spend something like a minimum of five hours a week on their coursework, the demands of work and family inevitably gain priority. The translation exercises are then done in a last-minute ditch on a last evening, or put off until next weekend, or simply postponed forever. Of course, these factors also concern students in face-to-face classes. Yet the very fact of attending a class is often a major source of motivation. A specific social environment is created when one’s body has been shifted into a specific learning environment where there are other bodies that have also made the trip (Pym, 2000).

8. Conclusion

The present paper is an attempt to shed light on several important resources that can enhance the translator’s training. Electronic and written translation resources can dramatically change the way in which a translator does his job. In the translation pedagogy, a lot of efforts are needed to reach a stage whereby a trainee in translation can self-train himself so efficiently to support the translation market, which suffers a lot from a dearth of qualified and ever self-developing translators, and this make obvious the necessity of well-organized pedagogy in translation study. With the ever-increasing use of Web sites for housing course contents, lessons, teaching units, etc., there has been a massive development in education software platforms. Teachers and theorists of translation pedagogy should always be on the lookout for new didactic strategies and methodologies in a continuous effort to enhance the teaching and learning process. Translation students, the final "clients" of education, deserve such an effort and so does the society they will hopefully work in one day. While finding didactic strategies and methodologies, all the advantages and disadvantages of this environment should be observed.

References:

Alcala, L. (2002). Status Questions of Distance Online Translator Training. A Brief Survey of American and European Translator- Training Institution. Available at: http://isg.urv.es/cttt/cttt/research/lopez.pdf.

Archer, J. (2002). Intemationalisation, Technology and Translation. Perspective Studies in Translatology. 87-117.

Aretio, L. G. (2001). La educación a distancia. De la teoria a la practica. Madrid: Ariel Educación.

Asensio, M. (2001). Translating Official Documents. Manchester : St.Jerome Publishing.

Askehave, I. (2000). The Internet for Teaching Translation. Perspectives: Studies in Translatology. 8 (2), 135-143.

Beeby, A. (1996). Teaching Translation from Spanish into English, Ottawa: Presses Universitaires.

Garcia, V. & Munoz, A. (ed.) (2001). Selected Papers on Distance Education, Madrid, La Muralla.

Graff, K. (1980). Correspondence Instruction in the History of the Western World in Selected Papers on Distance Education, quoted in Lorenzo García Aretio, (2001, p. 55).

Holmes, J. (1972). The Name and Nature of Translation Studies. expanded version in Translated! Papers on Literary Translation and Translation Studies, Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1988, 66-80.

Holmes, J. (1988). Translated! Amsterdam: Rodopi.

Kelly. M. & Kennell. T. & Sturn. M. (2002). An Analysis of Online and Distance Education Language Training. Available at: http://atwork.settlement.org/downloads/atwork/CIC_Fast_Forward_Online_Language_Training.pdf

Király, D.C. (1995). Pathways to Translation. Pedagogy and Process.Kent and London: The KentStateUniversity Press.

Noriko, H. & Kling, R. (2000). Students’ Distress with a Web-based Distance

Education Course: An Ethnographic Study of Participants’ Experiences’. Available at: http://www.slis.indiana.edu/CSI/wp00-01.html

Pym, A. (n.d.). E-Learning and Translator Training. Available from: http://www.ice.urv.es/trans/future/cttt/research/elearning.pdf

Toury, G. (1991). What are Descriptive Studies into Translation Likely to Yield apart from Isolated Descriptions?, in Kitty M. van Leuven-Zwart and Ton Naaijkens eds Translation Studies: The State of the Art, Amsterdam & Atlanta GA: Rodopi, 179-192.