|

Abstract

Effective machine interpretation (MI) or computer-assisted interpretation (CAI) is now a reality. However, most MI systems are capable of supporting only a few languages. This paper describes a new, portable prototype that is capable of recognizing unlimited vocabulary in 6 different languages, translating between any two of 51, and generating speech in 21. A test of spoken English to Korean shows that although there were several errors during the speech recognition and translation phases, the resulting speech was still acceptable.

Introduction

nterpretation is difficult and expensive, especially for relatively uncommon languages, and several research projects have attempted to solve this problem with technology. As shown in Table 1, fairly good speech-to-speech accuracies have been achieved, but most systems are limited to only a few languages, and some are limited to restricted domains, e.g. travel and tourism. nterpretation is difficult and expensive, especially for relatively uncommon languages, and several research projects have attempted to solve this problem with technology. As shown in Table 1, fairly good speech-to-speech accuracies have been achieved, but most systems are limited to only a few languages, and some are limited to restricted domains, e.g. travel and tourism.

Table 1: A brief survey of machine interpretation research

|

System |

Reference |

Resulting accuracy |

|

ASURA |

Morimoto, et al., 1993 |

Japanese to English; Japanese to German: High accuracy and good efficiency |

|

JANUS-II |

Waibel, 1996 |

> 70% from English, German, or Spanish to English, German, Korean, Japanese, or Spanish |

|

Spoken Language Translator |

Carter, et al., 1997 |

English to Swedish (72%), English to French (66%), Swedish to English (62%), Swedish to French (47%), Swedish to Danish (74%), English to Danish (55%) |

|

Sync/Trans |

Matsubara, et al., 1999 |

82%-84.5% English to Japanese |

|

Vermobil |

Wahlster, 2000 |

80% between English, German, and Japanese |

|

EUTRANS |

Pastor, et al., 2001 |

80%, between English, Italian, and Spanish |

|

(No Name) |

Okumura, et al., 2002 |

83%-87% between English and Japanese |

|

TRIM |

Ogden, 2005 |

Chinese to Japanese (25%), Korean to Japanese (31%), English to Japanese (56%), and English to Chinese (67%) |

|

ATR |

Nakamura, et al., 2006 |

750 out of 990 between English and Chinese or Japanese |

|

MASTOR |

Martins, 2009 |

BLEU (English to Chinese: 35; Chinese to English: 29) |

|

IraqComm |

Garreau, 2009 |

70%-80% between English and Arabic |

Here, we describe a prototype system that uses commercial and free software to provide interpretation between unrestricted English and 20 different languages. With the purchase of additional software, the number of language pairs can be increased to 200 or more. In a limited test of the system using spoken English to generate Korean utterances, results show that the quality was considered acceptable to three objective reviewers.

The Prototype Machine Interpreter

We have developed a new MI system designated DGL for its three principle components (Dragon Systems - Google Translate - Lernout & Hauspie), and each of these parts is described in more detail below.

Speech Recognition—The first phase of MI, speech recognition (SR), was implemented for English with Dragon Systems Naturally Speaking Standard Edition version 6. The software can be purchased for about US $99 for use with Dutch, English, French, German, Italian, and Spanish, and several studies have demonstrated high accuracy. For example, one study showed that a speaker can achieve up to 99% accuracy at 150 words per minute under ideal conditions (Dragon, 2009), but a second found only 80% accuracy (Broughton, 2002), and a third found only 91%, adjusted for comprehension (Aiken & Wong, 2001).

- Language Translation—

The second phase was implemented with a free, Web-based service (Google Translate) that provides automatic translations among any of 51 different languages in 2,550 language pairs (Och, 2009). Good translations can be obtained among most Western European languages, but even when translations are poor, users can often tell "who did what to whom" (Garreau, 2009).

- Speech Synthesis—

The third phase was implemented with free, downloadable Lernout and Hauspie text-to-speech modules providing male and female voices for Dutch, English, French, German, Italian, Japanese, Korean, Portuguese, Russian, and Spanish. Additional modules can be purchased for languages such as Polish and Chinese, and several others can be implemented with similar sounding components. For example, the Dutch module can be used for Afrikaans, Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish; Italian for Romanian; Russian for Belarusian, Bulgarian, Ukrainian, and Serbian; and Spanish for Filipino and Galician. Thus, 11 additional languages can be supported for free, for a total of 21.

These components were integrated on a Microsoft Windows XP desktop computer using Visual Basic 2008, and if all six language versions of the SR program are purchased, approximately 120 language-pair combinations can be achieved immediately for interpretation.

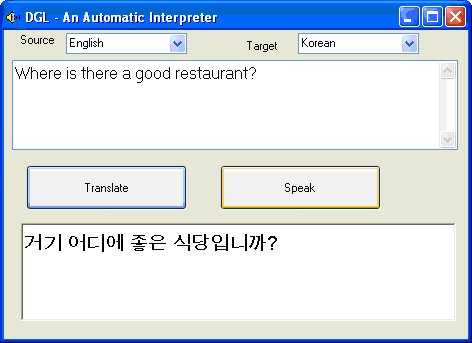

Figure 1 shows a sample screen of the system for interpretation between English and Korean. With Dragon Systems running in the background, a user simply places the cursor in the top text box and begins talking into a microphone. The SR program automatically transcribes text after groups of a few words are spoken. If recognition errors are made, the user can edit the text before clicking on the "Translate" button. The user has the option of editing the translated text before clicking the "Speak" button for the computer to generate the interpreted vocalization.

Figure 1: DGL sample screen—English to Korean interpretation

Evaluation

An adult, male, American, English speaker (subject 1) and an adult, female, Indian, English speaker (subject 2) individually trained Dragon Systems to recognize their voices through about an hour of training. Afterword, each spoke 42 travel phrases (188 words) in English from Fodor's (shown in Table 2).

Table 2: Speech recognition and translation results (bold shows major errors)

|

Original |

SR - Subject 1 |

Korean Translation after SR |

|

How much does that cost? |

How much does that cost? |

비용은 얼마입니까? |

|

At what time does the store open? |

At what time does the store open? |

몇 시에 가게를 열어 무엇입니까? |

|

At what time does the store close? |

At what time does the store close? |

몇시에 저장소를 닫습니까? |

|

What would you like? |

What would you like? |

무엇을 드시겠습니까? |

|

Can I help you? |

And I help you? |

그리고 내가 도와 줄까? |

|

I would like this. |

I would like this. |

제가하고 싶습니다. |

|

Here it is. |

Here it is. |

여기입니다. |

|

Is that all? |

Is that all? |

그게 다야? |

|

I would like to pay in cash. |

I would like to pay in cash. |

내가 현찰로 지불하고 싶습니다. |

|

I would like to pay by credit card. |

I would like to pay by credit card. |

신용 카드로 지불하고 싶습니다. |

|

Can I order this online? |

Can I order this online? |

제가 온라인으로 주문해도 될까요? |

|

Where is there a good restaurant? |

Where is there a good restaurant? |

거기 어디에 좋은 식당입니까? |

|

A table for 2, please. |

A table for 2, please. |

2 테이블하시기 바랍니다. |

|

The menu, please. |

The menu, please. |

메뉴에서하시기 바랍니다. |

|

The wine list, please. |

The wine list, please. |

와인리스트 부탁합니다. |

|

I would like something to drink. |

I would like something to drink. |

마실 것 좀하고 싶습니다. |

|

A glass of water, please. |

A glass of water, please. |

물 한 잔 부탁합니다. |

|

Do you have a vegetarian dish? |

Do you have a vegetarian dish? |

당신이 채식 요리를 가지고 있나요? |

|

I like my steak well done. |

I like my steak well done. |

제가 스테이크를 좋아 잘했어. |

|

I like my steak rare. |

I like my steak rare. |

내 스테이크 희귀 좋아. |

|

I had a wonderful time. |

I had a wonderful time. |

난 멋진 시간을했다. |

|

This is my girlfriend. |

This is my girlfriend. |

이건 내 여자 친구입니다. |

|

This is my boyfriend. |

This is my boyfriend. |

이것은 제 남자 친구입니다. |

|

This is my friend. |

This is my friend. |

이쪽은 제 친구입니다. |

|

Where do you live? |

Where you live? |

넌 어디에 사니? |

|

I live in New York. |

I live in New York. |

난 지금 뉴욕에 살고있다. |

|

It's nice to meet you. |

It's nice to meet you. |

만나서 반갑습니다. |

|

What is your name? |

What is your name? |

이름이 무엇입니까? |

|

How are you? |

How are you? |

어떻게 지내세요? |

|

Is it near? |

Is it near? |

근처에 있나요? |

|

Is it far? |

Isn't far? |

그리 멀지 않은 가요? |

|

Go straight ahead. |

Go straight ahead. |

똑바로 말하라. |

|

Go that way. |

Do that way. |

그런식으로 마십시오. |

|

Turn right. |

Turn right. |

우회전. |

|

Turn left. |

Turn left. |

좌회전. |

|

Take me to this address. |

Take me to this address. |

이 주소로 해주세요. |

|

What is the fare? |

What is the fare? |

어떤 요금입니까? |

|

Stop here. |

Stop here. |

여기를 중지합니다. |

|

I would like a map of this city. |

I would like a map of this city. |

난이 도시의지도를하고 싶습니다. |

|

Where are the taxis? |

Where are the taxis? |

택시는 어디입니까? |

|

Where is the subway? |

Where is the subway? |

지하철은 어디입니까? |

|

Where is the exit? |

Where is the exit? |

출구는 어디인가? |

As indicated above, the SR program did not recognize a few words, and subject 1 achieved a word error rate of 2.1% and a BLEU score ( Papineni, et al., 2002) of 95.6 (maximum 100). The program did not recognize several of subject 2's words, however, and she achieved a BLEU score of only 70.5. Speech recognition errors are common in MI research, as one study (Okumura, et al., 2002) had a 14%-15% word error rate, and another (Waibel, 1996) had a word error rate of 29%. These errors can significantly affect the following translation phase.

Three native Korean speakers were asked to evaluate the translations for comprehension using the scale:

1=do not understand at all, 2=mostly do not understand, 3=misunderstand more than understand, 4=no opinion, 5=understand more than misunderstand, 6=mostly understand, and 7= understand very clearly. For subject 1, the mean score for comprehension was 6.02 with a standard deviation of 1.25. Using the same scale, they were also asked how well all of the comments together should be understood, and the mean score was 4.67. Using this threshold, the comprehension was significantly higher than that required (t = 6.68, p < 0.001). For subject 2, the mean comprehension was only 4.96 with a standard deviation of 2.08, primarily because so many words were not recognized during the SR phase. Nevertheless, the comprehension was still higher than that required.

For the speech synthesis phase, the three were asked to evaluate the sentences in Table 3, spoken by the system in Korean.

Table 3: Comments for evaluating the speech synthesis phase

|

English equivalent |

Spoken Korean |

|

How have you been doing?

|

어떻게 지내셨습니까? |

|

How many cities in the U.S.A. have you visited?

|

미국 내 얼마나 많은 도시를 방문했습니까? |

|

Is it going to snow a lot tomorrow?

|

내일 눈이 많이 옵니까? |

|

When do you plan to go back to Korea?

|

언제 한국으로 돌아갈 계획입니까? |

For each spoken sentence, each user gave the system a perfect score of 7 on the 1-to-7 scale, but they noted that the female voice sounded like someone reading a book rather than talking in a conversation. Even unknown words such as the sound animals might make, when written in Korean, were heard correctly.

Discussion

The study suffers from several limitations. First, only two English speakers were used and only three Koreans evaluated the results. Other speakers might generate different SR errors, and other evaluators could have different opinions about comprehension. Second, only one source language (English) and one target language (Korean) were tested. Accuracies with other language combinations are likely to be different (Aiken & Park, 2010; Aiken, et al., 2009). Third, the system was not tested in the field. Background noise can severely degrade the quality of the speech recognition. Finally, the system is not self-contained, as it relies upon Internet access for the Google Translate service. Therefore, the system is not completely portable.

Nevertheless, we believe this pilot study demonstrates the potential of the prototype. It is capable of generating speech with adequate comprehension for English to Korean, and a large number of language combinations are possible. With extra programming, even more languages can be accommodated. By converting text into phonemes, adjusting the pitch and pauses, Swahili can be spoken using the English text-to-speech module, for example. Thus, the other 30 or so languages currently available with Google Translate could be accommodated. With the use of 11 different SR language modules from Via Voice (Chinese, Dutch, English, French, German, Italian, Japanese, Korean, Portuguese, Spanish, and Swedish), up to 11 x 50 = 550 language-pair combinations can be achieved.

In addition, even if the system cannot currently speak some languages, such as Arabic and Hindi, it is capable of generating text in these tongues. People can generate more words speaking with SR than typing, and the translated text could be read rather than heard.

Conclusion

This paper has described a prototype system for machine interpretation that currently supports 20 language-pair combinations, but has the potential for up to 550. In a test of English to Korean interpretation, there were several errors due to poor speech recognition and translation, but the spoken result was still comprehensible enough. Other language combinations could produce worse results, but many are likely to produce better, especially when interpreting between Western European languages.

References

- Aiken, M. and Park, M. (2010). The Efficacy of Round-trip Translation for MT Evaluation. Translation Journal, 14(1), January.

- Aiken, M., Park, M., Simmons, L., and Lindblom, T. (2009). Automatic Translation in Multilingual Electronic Meetings. Translation Journal, 13(9), July.

- Aiken, M. and Wong, Z. (2001). The influence of textual complexity on automatic speech recognition. Proceedings of the 32nd Annual Meeting of the Decision Sciences Institute, San Francisco California, November 17-20.

- Broughton, M. (2002). Measuring the accuracy of commercial automated speech recognition systems during conversational speech. Virtual Conversational Characters (VCC) Workshop, Human Factors Conference, Melbourne, Australia, December.

- Carter, D., Eklund, R., Kirchmeier-Andersen, S., Becket, R., MacDermid, C., Philp, C., Rayner, M., Wiren, M. (1997). Translation Methodology in the Spoken Language Translator: An Evaluation, Proceedings of a Workshop Sponsored by the Association of Computational Linguistics and by the European Network in Language and Speech (ELSNET), 73-82.

- Dragon (2009). Dragon Naturally Speaking.

- Garreau, J. (2009). Tongue in check. Washington Post (DC) (05/24/09).

- Martins, C. (2006). Translation software put to the test. PC World.

- M

atsubara, S., Toyama, K., and Inagaki, Y. (1999). Sync/Trans: Simultaneous machine interpretation between English and Japanese. Advanced Topics in Artificial Intelligence. Springer: Berlin.

- Morimoto, T., Takezawa, T., Yato, F., Sagayama, S., Tashiro, T., Nagata, M., and Kurematsu, A. (1993). ATR's speech translation system: ASURA. EUROSPEECH 1993 Third European Conference on Speech Communication and Technology. Berlin, Germany, September 22-25.

- Nakamura, S., Markov, K., Nakaiwa, H., Kikui, G., Kawai, H., Jitsuhiro, T., Jin-Song Z., Yamamoto, H., Sumita, E., and Yamamoto, S. (2006). The ATR multilingual speech-to-speech translation system. IEEE Transactions on Audio, Speech, and Language Processing, 14(2), 365-376.

- Och, F. (2009). 51 Languages in Google Translate. Google Research Blog.

- Ogden, B. (2005). Computer mediated multilingual translation. Computing Research Lab, New Mexico State University.

- Okumura, A., Iso, K., Doi, S., Yamabana, K., Hanazawa, K., and Watanabe, T. (2002). An automatic speech translation system for travel conversation. NEC Research and Development, 43(1), 37-40.

- Papineni, K., Roukos, S., Ward, T., and Zhu, W. (2002). BLEU: A method for automatic evaluation of machine translation. Proceedings of the 40th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL), Philadelphia, July, 2002, 311-318.

- Pastor, M., Sanchis, A., Casacuberta, F., and Vidal, E. (2001). EUTRANS: A speech-to-speech translator prototype. Proceedings of EUROSPEECH 2001, 2385-2388.

- Wahlster, W. (2009). Mobile speech-to-speech translation of spontaneous dialogs: An overview of the final Verbmobil system.

- Waibel, A. (1996). Interactive translation of conversational speech. Computer, 29(7), 41-48.

|